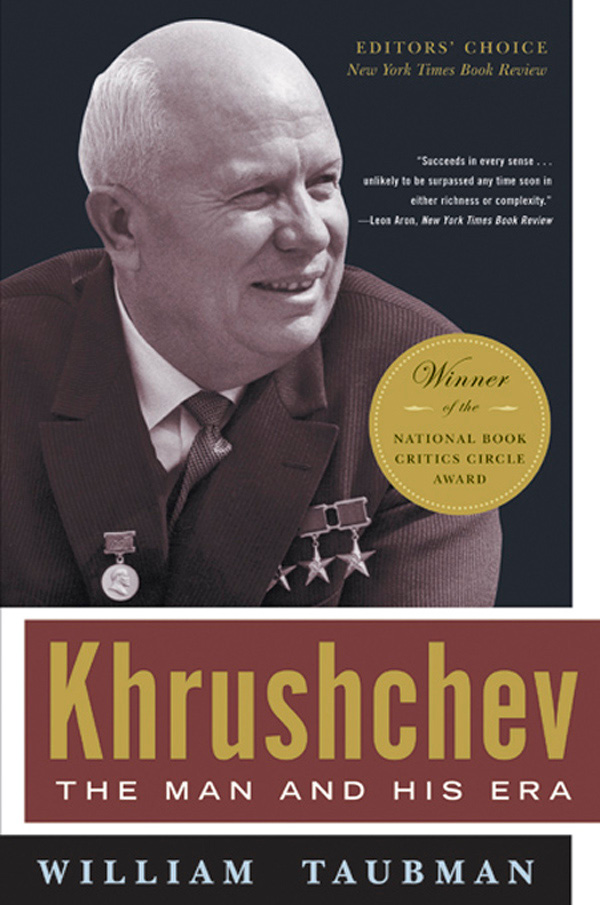

KHRUSHCHEV

THE MAN

AND

HIS ERA

WILLIAM TAUBMAN

W. W. Norton & Company

NEW YORK LONDON

To the memory of my parents,

Nora and Howard Taubman

CONTENTS

Note on Russian and

Ukrainian Usage

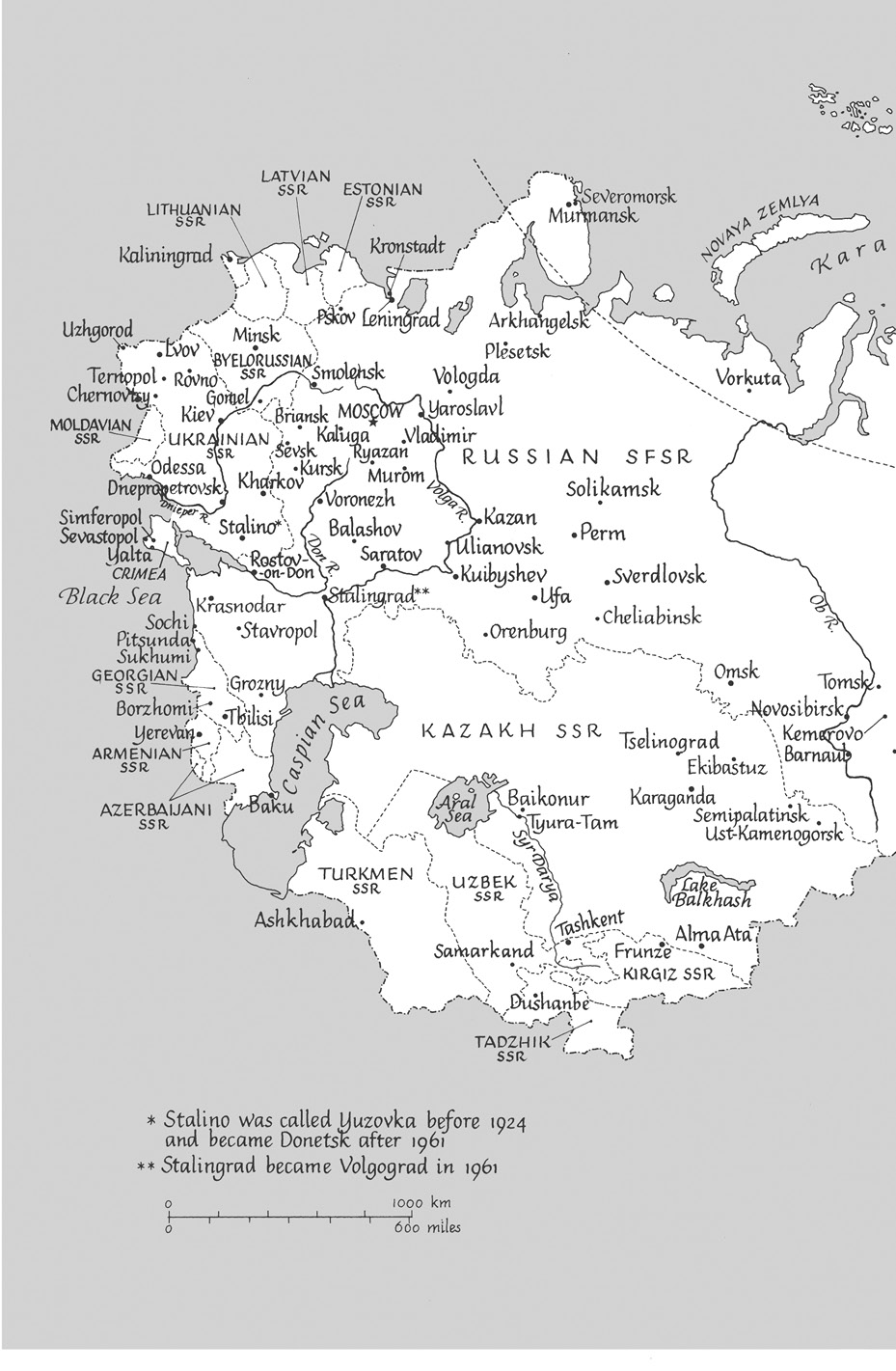

There are several systems of transliteration of the Russian language. Throughout the text of this book I have used transliterations that will be most familiar or most accessible to the reader and most likely to capture the sound of Russian. However, in the Notes and Bibliography, when I cite specific Russian-language material, I employ the Library of Congress transliteration system, which is often used in library catalogs. So, for example, although Oleg Troyanovsky, one of Khrushchevs aides, appears as such in the text, when I refer to his Russian-language memoir, I spell his name Troianovskii.

During almost the entire period covered in this book, Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire and later of the Soviet Union. In that time Russian versions of Ukrainian personal and place-names were used in official, and often in informal, discourse. For that reason, and to avoid confusing readers, I use those Russian versions. However, for books and articles published, and interviews conducted, when Ukraine was an independent state, Ukrainian place-names are used. In the Index, Ukrainian public figures are identified by both Russian and Ukrainian versions of their names.

PREFACE

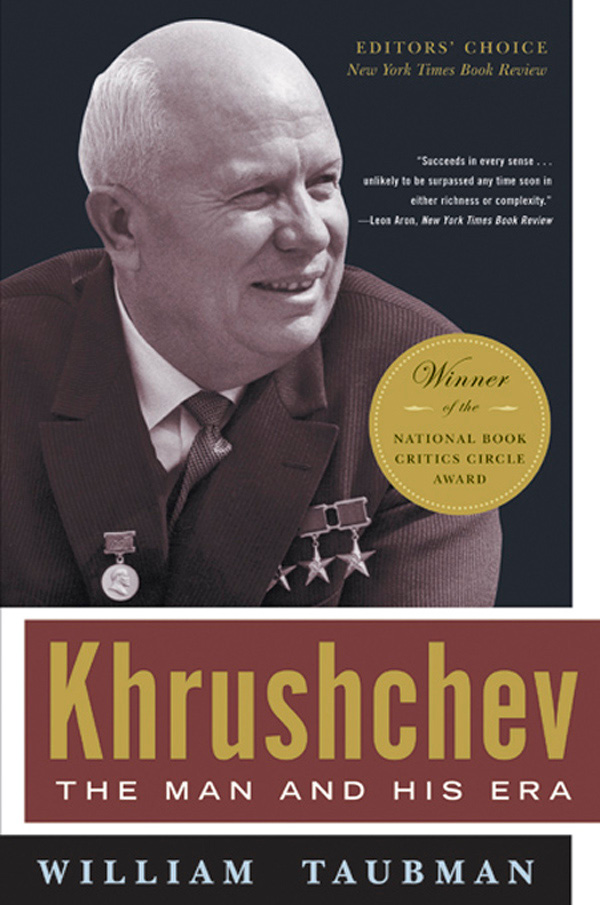

Ask many Westerners, and not a few Russians, and theyre likely to recall Nikita Khrushchev as a crude, ill-educated clown who banged his shoe at the United Nations. But the short, thick-set man with small, piercing eyes, protruding ears, and apparently unquenchable energy wasnt a Soviet joke even though he figures in so many of them. Rather, he was a complex man whose story combines triumph and tragedy for his country as well as himself.

Complicit in Stalinist crimes, Khrushchev attempted to de-Stalinize the Soviet Union. His daring but bumbling attempt to reform communism began the long, erratic process of putting a human face (initially his own) on an inhumane system. Not only did he help prepare the way for Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin a quarter of a century later, but Khrushchevs failure to set a stable and prosperous new course for his country anticipated the setbacks that would thwart their attempts at reform.

I saw Khrushchev for the first and only time in September 1959. Just before returning to college for my sophomore year, I caught a glimpse of him as his limousine drove through New Yorks Central Park during his tumultuous tour of the United States. In 1964, while on a Russian language-study tour of the USSR, I descended into a coal mine in Donetsk, Ukraine, where Khrushchev had worked as a young man. By the time I spent the academic year 19651966 as an exchange student at Moscow State University, he was out of power and in official disgrace. My student friends were grateful to Khrushchev for unmasking Stalins crimes but ashamed that a man they regarded as a boor had been their countrys leader. They reserved both a special affection and special disdain for Khrushchev, a combination that I cant help feeling myself as I finish writing his biography.

In the early 1980s, after writing the book Stalins American Policy , I began to examine Khrushchevs American policy. Yet I soon found his personality more fascinating than his foreign policy, so I opted for a biography instead. If I had delivered the manuscript in 1989 as originally promised, the result would have been very different from this book.

During his time as Communist party leader, Khrushchev was remarkably loquacious. His speeches on agriculture alone fill eight volumes; In the mid- 1980s Soviet party archives were still off-limits, and most Western documents from Khrushchevs reign had not yet been declassified. As late as 1988 , when I spent five months in Moscow on the academic exchange program, I thought I couldnt admit that my subject was Khrushchev (instead I called it the origins of U.S.-Soviet dtente) lest I alarm the Soviet authorities, although in retrospect, I think I was probably more cautious than they were. I managed to interview just a handful of people who had connections with Khrushchev; it was only at the very end of my stay that I arranged to telephone, but not actually to meet, Khrushchevs son Sergei.

By 1991 the situation had changed radically. Khrushchev-era memoirs had begun to appear (including books by Sergei and by Nikita Khrushchevs son-in-law Aleksei Adzhubei, the former editor of the government newspaper Izvestia ); a third volume of Khrushchevs memoirs (containing material he had held back in 1970 ) was published in the United States; and an edition of his recollections, prepared by Sergei Khrushchev, started coming out in the history journal Voprosy istorii .

With the fall of the USSR, long-closed Soviet archives finally opened, erratically and not necessarily permanently, but at least for a while. The Presidential Archive (formerly the Politburo Archive), which contains particularly sensitive material on Soviet leaders, and the KGB archives remain closed to all but a favored few, but key party depositories became accessible, not only in Moscow but throughout the former Soviet Union. Fortunately, some of these turned out to contain carbon copies of documents that the secretive Soviets thought had been preserved in the Politburo Archive alone.

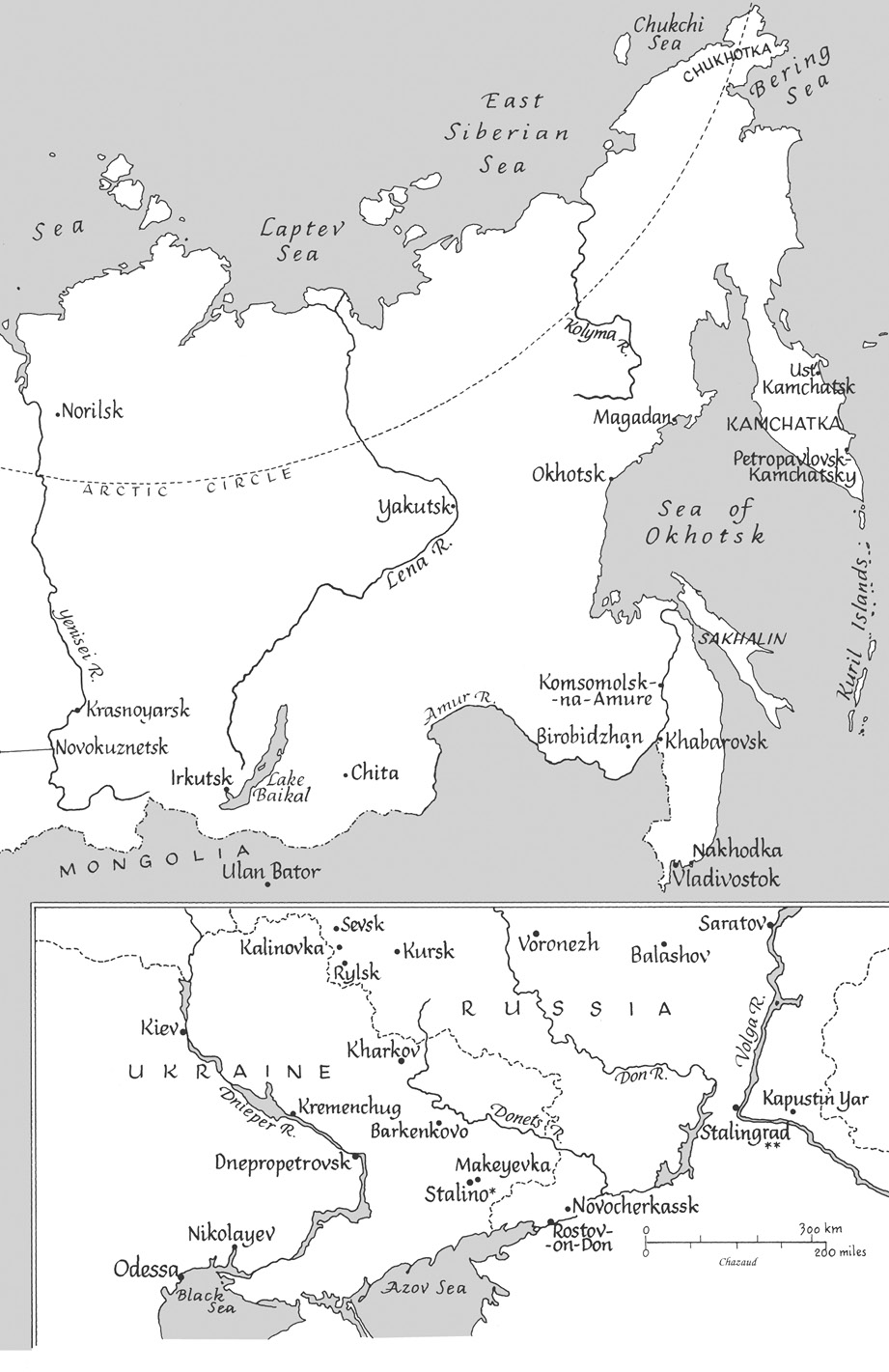

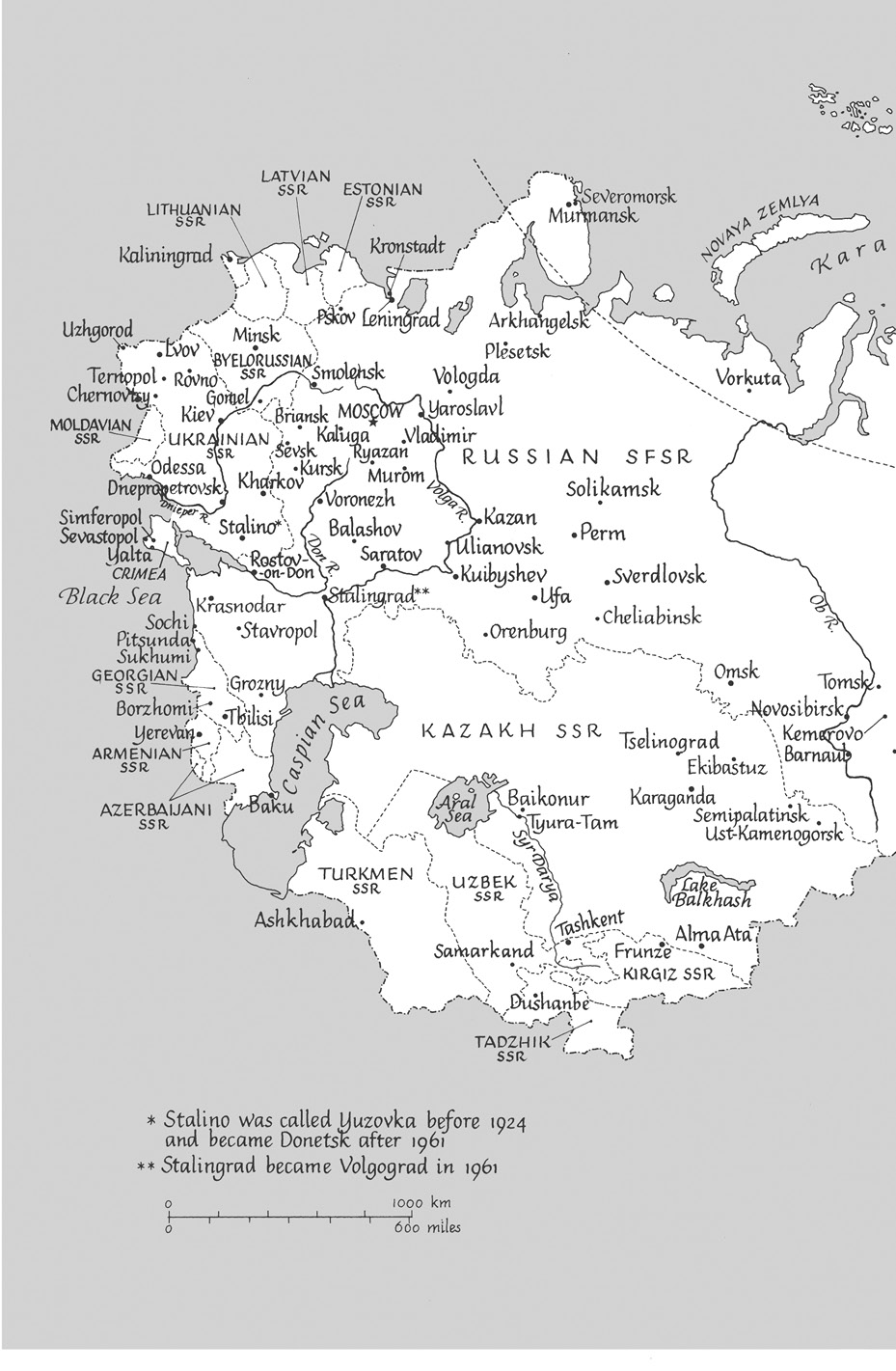

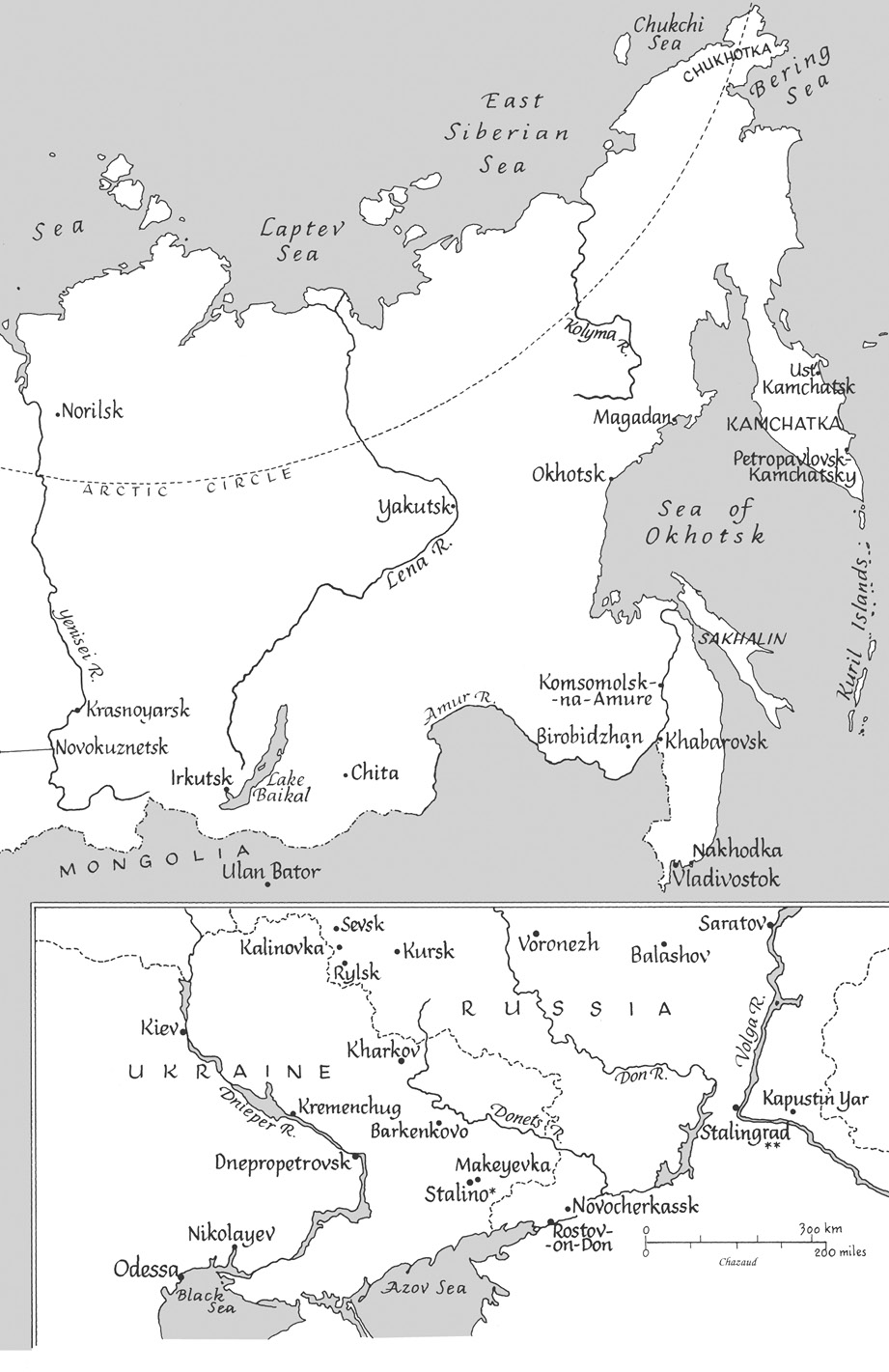

Over the next ten years I worked off and on in archives in Moscow, Kiev, and Donetsk and interviewed Khrushchev family members, Kremlin colleagues, subordinates who worked for and against him, and people who knew him long before he succeeded Stalin in 1953. With the help of Sergei Khrushchev, I traveled to Nikita Khrushchevs birthplace in Kalinovka and visited his adolescent haunts in eastern Ukraine. Since the Soviet era was only just over, some former officials I wished to see were still reluctant to talk to an American, while archivists were unsure what they could safely show. In that sense, my efforts to track people down, to get them to see me and to talk candidly, and to unearth long-hidden documents involved as much detective work as it did traditional academic research.

My next challenge became how to organize and interpret all this material. Until the fall of the USSR, and especially during the Gorbachev era, the key questions about Khrushchev concerned his reforms: why and how he attempted them and why they largely miscarried. Since 1991, however, Khrushchevs career has assumed a larger meaning. For taken in its entirety, his life holds a mirror to the Soviet age as a whole. Revolution, civil war, collectivization and industrialization, terror, world war, cold war, late Stalinism, post-StalinismKhrushchev took part in them all. What attracted so many men and women to revolution and communism? What kept them loyal after the terrible bloodletting began? What led at least some of them to break with their own past and try to reform the regime? Finally, what frustrated and defeated them, bringing on a long era of stagnation followed by the fall of the Soviet Union itself? Khrushchevs biography can provide at least some of the answers.

Next page