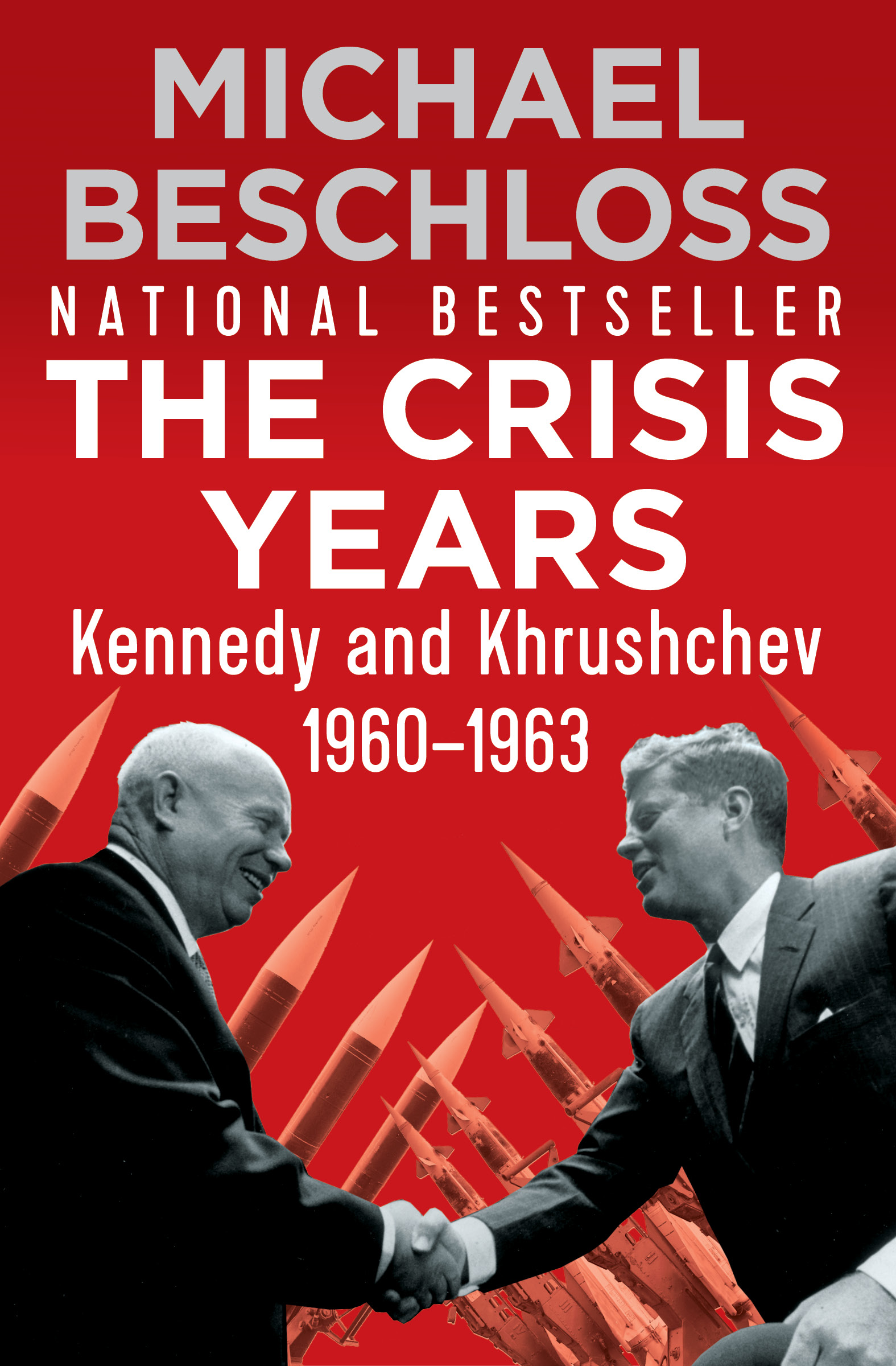

The Crisis Years

Kennedy and Krushchev

19601963

Michael Beschloss

For Afsaneh Mashayekhi

PREFACE

This volume examines the relationship of John Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev and its impact on the Cold War. Why did these two leaders, who both came to power with genuine hopes of reducing the harshness of Soviet-American relations, take humankind instead to the edge of nuclear disaster and into the most ferocious arms race in world history?

The book benefits from new scholarship and new information on the Kennedy-Khrushchev period. Like every scholar, I stand on the shoulders of many others and am happy to here express my debt to all of those who have gone before me. Recent years have seen the opening of the majority of John Kennedys papers bearing on the Soviet Union and of other archives shedding light on his relations with Nikita Khrushchev. American political, military, and intelligence officials of the period have become more willing to be interviewed at length about sensitive aspects of their service. Thanks to a Harvard group, Soviet and American officials and historians have gathered to reexamine the crises over Berlin and Cuba.

In my last book, Mayday: Eisenhower, Khrushchev and the U-2 Affair, expectations that at last historians can write with equal access to Soviet and American sources. This book does benefit from hundreds of oral and written reminiscences by Soviet figures that were not until recently available. These expand our knowledge and understanding of Soviet decision-making.

Still I have used them with considerable self-restraint, for they are subject to the same partisan motives, faulty memories, and other limitations that distort Western oral history and memoir. Unlike in the West, we do not yet have access to a substantial number of contemporaneous official Soviet documents that might help us to better judge their accuracy. Until the Soviet government opens its classified archives to Western scholars, volumes such as this one must be more tentative in their treatment of the Soviet than the Western side. Until that time, no scholar can aspire to write a fully comprehensive or reliable history of any portion of the Cold War.

Information is not the only ingredient vital to historiography. So is the passage of time. It is difficult to think of two leaders whose reputations have oscillated more wildly in three decades than those of Khrushchev and Kennedy. The distance of thirty years allows us to look at both men with greater dispassion.

The end of the Cold War enables us to study that dangerous half century not as an earlier phase of current politics but as a discrete epoch. By exploiting the assets of retrospect and increasing information, historians in both East and West can begin to work toward consensus on the overarching questions of why that epoch started, why it ended, and how to prevent another such tragic and costly struggle.

M ICHAEL R. B ESCHLOSS

Washington, D.C.

March 1991

Harper & Row, 1986, p. xvi.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Almost Midnight

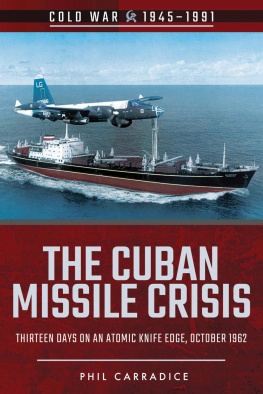

On Sunday morning, October 14, 1962, John Fitzgerald Kennedy awoke at the Penn Sheraton Hotel in Pittsburgh, there to campaign for Democrats running in the 1962 elections. He did not know it yet, but this was the eve of a military confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union that was potentially the most dangerous ever.

The President attended Sunday Mass and flew to Niagara Falls, New York, where he climbed into an open car for a motorcade into Buffalo. A girl jumped up and down, shouting, I can see his hair! I can see his hair! After speaking on the steps of the Buffalo City Hall, he was scheduled to fly back to Washington in midafternoon.

Then his press secretary, Pierre Salinger, told reporters that there had been a sudden shift of plans: now the President would stop in New York City on Sunday evening to consult with Adlai Stevenson, his Ambassador to the United Nations.

Stevenson had been spending a weekend with friends at Rhinebeck on the Hudson when asked to rush to the Presidents side. Flown by helicopter to New York Citys Idlewild Airport at 6:35 P.M. , he was still wearing a country tweed jacket and sweater when he shook Kennedys hand and followed him into the presidential limousine.

The two men were driven to the Carlyle Hotel, where the President kept a thirty-fourth-floor duplex with antique French furniture and glittering night views of Manhattan. He chatted with Stevenson for an hour about Cuba and the Congo. Then Stevenson left the hotel, telling reporters, Just a routine briefing.

The newsmen did not discover that Stevenson was quietly followed into Kennedys suite by the Presidents gregarious old Harvard roommate, Torbert Macdonald, a Congressman from Malden, Massachusetts. Dinner was brought in. After three hours, Kennedy and Macdonald emerged from the Carlyle and were driven to La Guardia Airport, where they boarded Air Force One, bound for Washington.

Far below the presidential plane as it swept over Washington was an outpost of the Central Intelligence Agency, hidden on an upper floor of a car dealership five blocks from the floodlit U.S. Capitol. Inside the darkened suite, photo experts leaned over light boxes, staring at images taken that morning of Fidel Castros Cuba. A U-2 spy plane had provided the first close look in five weeks at the western reaches of the island.

Secret agents and Cuban exiles had reported to the CIA that the Soviet Union was moving missiles into western Cuba capable of launching nuclear warheads against the United States. Kennedy had sent the U-2 to assure himself that these reports were wrong.

His Sovietologists had reminded him that Nikita Khrushchev had never allowed Soviet nuclear missiles to go outside the Soviet Union. They had insisted that the Chairman would never be so reckless as to send them in secret to an area so close to the United States and an island ruled by a leader so erratic and unpredictable as Castro.

On Monday, weary from campaigning and his late night at the Carlyle, the President did not arrive at the Oval Office until 11:27 A.M. , almost three hours later than usual. As he sat down at the famous desk carved from the timbers of the H.M.S. Resolute, his back hurt. On the South Grounds of the White House, the Army Band was tuning up and crowds were gathering for the landing by Marine helicopter of Ahmed Ben Bella, Prime Minister of newly independent Algeria.

Every morning, in bed or in his office, Kennedy donned the horn-rimmed reading glasses he never wore in public and looked through a top-secret document called The Presidents Intelligence Checklist. The CIA tailored this paper to the reading habits of each President it served. Under Kennedy, the Checklist used the almost wise-guy language that the President and his intimates used in private.

This mornings edition said, The Saudis, fed up with the unending overflights of their territory by Egyptian aircraft, have obliquely warned Cairo to knock it off. A well-placed source in Vientiane tells us that the cabinet on Friday was treated to a blistering harangue by Phoumi Vongvichit of the Pathet Lao.

The men at the Agency knew that this Presidents attention could be caught by salacious secrets about foreign leaders. Kennedy was intrigued to hear that the President of Brazil, Joo Goulart, had had his wifes lover shot to death. He was given a transcript showing what the belligerent West German Defense Minister, Franz-Josef Strauss, talks like when drunk.