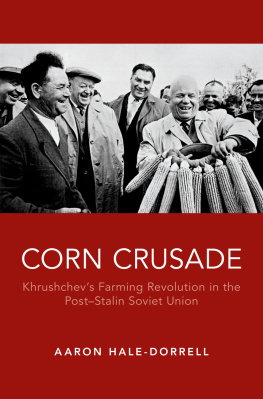

CORN CRUSADE

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hale-Dorrell, Aaron Todd, author.

Title: Corn crusade : Khrushchevs farming revolution in the post-Stalin

Soviet Union / Aaron Hale-Dorrell.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2018. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018019524 (print) | LCCN 2018028937 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190644680 (updf) | ISBN 9780190644697 (epub) |

ISBN 9780190644703 (online component) | ISBN 9780190644673 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeevich, 18941971. |

Corn industrySoviet UnionHistory20th century. |

CornGovernment policySoviet UnionHistory20th century. |

Agriculture and stateSoviet UnionHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HD9049.C8 (ebook) | LCC HD9049.C8 S738 2018 (print) |

DDC 338.1/7315094709045dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019524

Contents

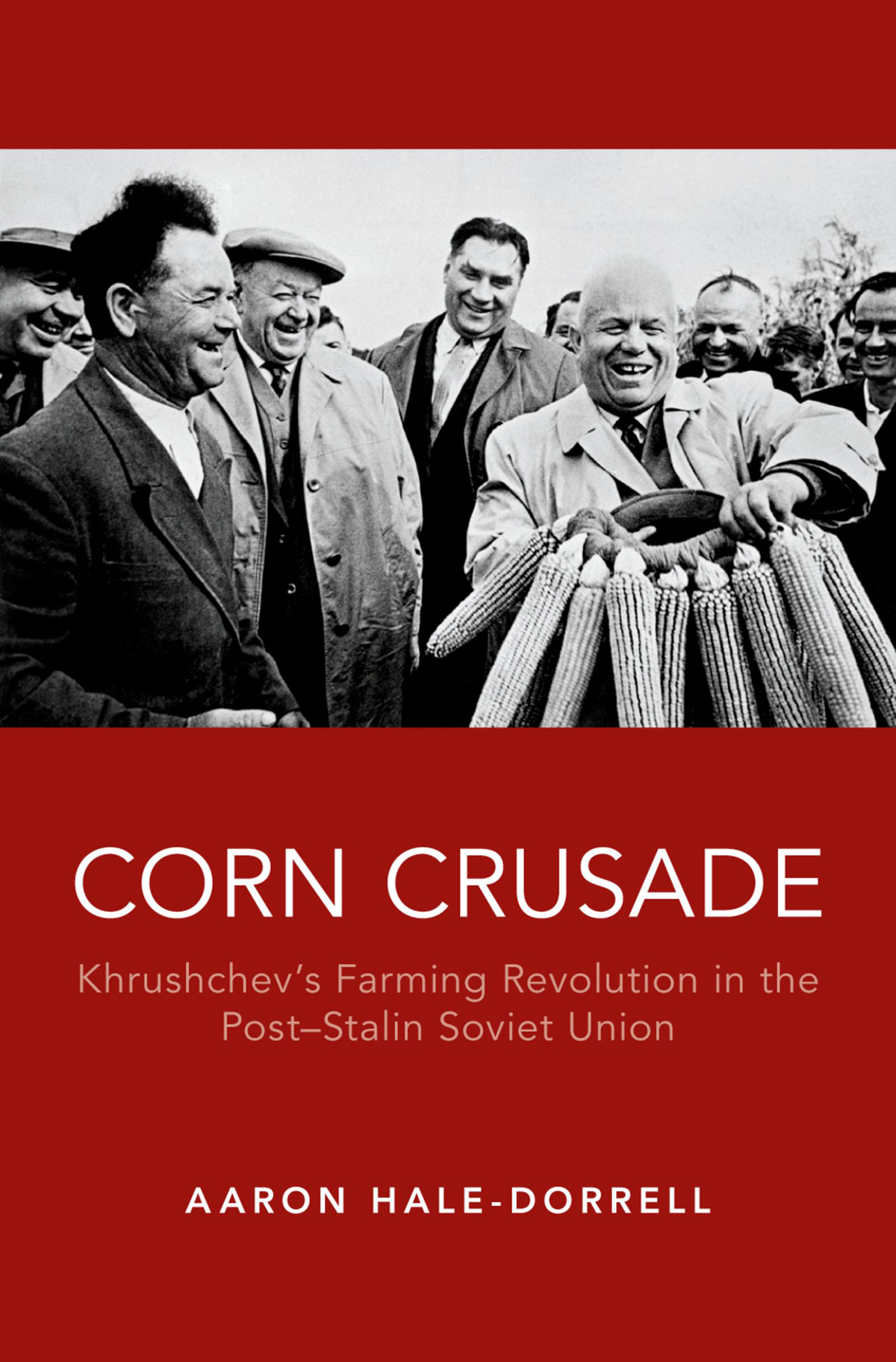

Meant to feed the livestock necessary to provide citizens a rich and varied diet, corn was to contribute to domestic stability, the abundance required by Khrushchevs concept of communism, and success in the Cold War contest against the United States, which he reimagined as a peaceful competition to provide higher living standards. Scholars have long dismissed this corngrowing strategy as irresponsible because the crop demanded warm, humid summers that much of the Soviet Union lacked. Yet a story of climate alone captures only part of a history of modest successes, policy blunders, and the everyday dysfunction inherited from Iosif Stalin.

Long before Khrushchev, rulers of Russia had imposed potentially useful innovations, only to see them frustrated by the realities of governing. The satirist Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin caricatured overbearing sovereigns attempts to reform an empire and people so apparently intractable. His History of a Town, published in 1870, takes the form of a fanciful chronicle of Glupova name derived from the Russian glupyi, or foolishthat serves as an allegory for the whole of Russia. Many town governors benignly neglected their duties, but the dangerous ones aimed to improve the people, culture, and economy.

One of the latter, Vasilisk Borodavkin, resurrected the reforms of Dvoekurov, a predecessor who had been so progressive as to institute discriminant flogging in place of indiscriminant and to compel the townspeople to cultivate mustard. The latter initiative had nonetheless provoked disturbances. Wherever theres flogging, you can bet your life theres a rebellion.... A lot even went to Siberia over that business! the citizens informed Borodavkin when he inquired about Dvoekurovs mustard experiment. Speaking in some detail concerning the basis of society in general, and of mustard as the basis of society in particular, Borodavkin tried to convince the inhabitants to grow it again. The chronicle

Saltykov-Shchedrin drew inspiration for the mustard-planting scheme from efforts during the reign of Catherine the Great in the eighteenth century to coerce peasants to plant potatoes, another unfamiliar New World crop. In a 2011 interview, Sergei Khrushchev linked his fathers program to that episode. He contended that historians misrepresent the policies by claiming that Khrushchev brought corn from America to plant it beyond the Arctic Circle. Defending his fathers legacy, the younger Khrushchev continued, Of course, this was not the case. Father simply ascertained that... corn contained the maximum amount of feed, and said, Lets adopt that. Corn became a joke, but there were no corn rebellions like the potato rebellions of Catherines time. Or, at least, no one overtly revolted.

In hindsight, my decision to write first a doctoral dissertation and then this book about Khrushchevs devotion to corn seems only logical. Fascinated by the Soviet Union, I noticed that many historians offered only a cursory explanation for the seemingly quixotic scheme. Yet the episode spoke to my experience growing up in Americas rural Midwest, where corn is king. In June and July of the summer I turned fourteen, I spent several weeks detasseling corn, a job description likely familiar only to readers raised in the Corn Belt, home to commercial production of hybrid seeds. The work meant getting up before sunrise to ride a school bus to a field. There, from dewy morning to sweltering midday, a crew of teenagers manually completed a job begun by a machine designed to chop the pollen-producing top, the tassel, from corn plants in rows each composed of one genetically uniform line. This ensured that they were pollinated by plants of a different line in a neighboring row, which kept their tassels. This produced seeds sharing desirable characteristics of both lines. Earning only minimum wage, the job functioned as a rite of passage teaching the value of manual labor. Although I returned each working day that summer, by its end I had my fill of tassels. Little did I know that I would recall that work years later while sitting in a Moscow archive reading reports to the Central Committee of the Young Communist League. It turns out that beginning in the late 1950s, teenagers across the Soviet Unions southwestern reaches did the same job as part of Khrushchevs corngrowing program.

I could never have succeeded in the field of history without the many people who helped me along the way and thereby made this book possible. Like all products of academic labor, it would have been impossible without the help, advice, support, and encouragement of colleagues, friends, and family. This book began as my doctoral dissertation at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which I completed under the expert guidance of Donald J. Raleigh. I cannot sufficiently acknowledge all that Don taught me about the craft of history and the hard work of writing it, both of which were substantial, time-consuming endeavors. Moreover, he consistently demonstrated what it meant to be a scholar and mentor.

In the department of history, I also benefited from the mentorship of Louise McReynolds and Chad Bryant, who each readily offered advice and encouragement through every phase of the project. Other faculty members contributed to my graduate training in teaching and scholarship in ways that, while perhaps not obvious, shaped my approach to the topic and to the work that went into the project. Christopher Browning, Donald Reid, Michael Tsin, Lisa Lindsay, Christopher Lee, Miles Fletcher, Marcus Bull, and Theda Perdue all belong on this long list, which is nonetheless not exhaustive.