Dedication and Acknowledgments

To Wendy and Richard, my two main corn lovers.

A big thanks to all the people at Storey Books who made Corn a possibility. I feel fortunate to have collaborated with such a good crew. It takes a lot of work by a lot of people to get a book through the production line, into the stores, and into the public eye, and I couldnt have done it without your help.

Special thanks go to my editor Dianne Cutillo, whose creative editorial and organizational skills were the driving force behind this revision. She is an inspirational editor to work with. Project editor Karen Levy, for her Sherlock Holmesian instincts to sift through so many facts and details. Publicity manager Stephanie Taylor, and all the sales associates.

The following people, who generously shared their recipes: Brian and Margaret Ann Ball of The Red Fox Restaurant in Snowshoe, West Virginia; Susan Curtis, owner and director of the Santa Fe School of Cooking in Santa Fe, New Mexico; Ross Edwards; Michael Kramer, partner and executive chef of McCradys restaurant in Charleston, South Carolina; Megan Moore of Moore Fine Food in Great Barrington, Massachusetts; Christy Velie, head chef at Caf Atlntico in Washington, DC; and the Zurschmeide family of Great Country Farms in Bluemont, Virginia.

The following people and organizations, for furthering my education about corn: Tony Bratch, commercial horticulture specialist at Virginia Tech in Blackburn, Virginia; Debbie Dillion, urban horticulturist at Loudoun County Extension in Leesburg, Virginia; Cary Nalls of Nalls Farm Market in Alexandria, Virginia; The National Corn Growers Association; state corn growers associations and associated state universities; Lori Warner at The Popcorn Institute in Chicago, Illinois; The Virginia Corn Growers Association; The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services; and Bruce Zurschmeide.

Contents

Preface

O beautiful for spacious skies,

For amber waves of grain,

For purple mountain majesties

Above the fruited plain!

America! America!

God shed His grace on thee

And crown thy good with brotherhood

From sea to shining sea!

When Katharine Lee Bates wrote these famous lines in 1893, she was on top of Pikes Peak in Colorado Springs. Looking down over the plains, she was overcome by the beauty of her country. Although the amber waves of grain she saw were most likely prairie grasses or acres of wheat, her evocation could easily apply to vast fields of corn with their golden tassels gleaming in the summer sun or bronzed corn stalks heavy with ears of dried ornamental corn.

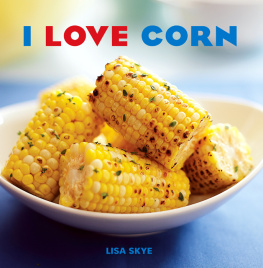

With its bright green husk and ornamental golden tassel, corn has been a motif in American art since prehistoric times. In fact, there is no vegetable, or fruit, more exclusively American than corn. It is the symbol of our bountiful land and of summers abundant harvest. Indeed, for thousands of years, the appearance of the first crop of ripe corn has been cause for celebration. Today, corn is celebrated throughout the world as a major food source for humans and animals. And with its myriad by-products, corn is the fiber in the fabric of life that binds the Americas to the rest of the world from sea to shining sea and from the mountains to the plains.

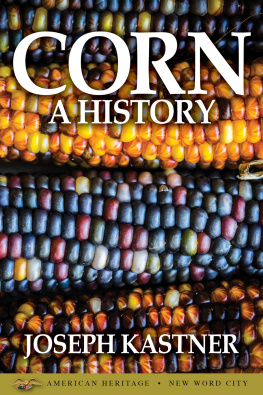

The History of Corn

Corn is the only important grain indigenous to the Western Hemisphere, and its proliferation has sown the seeds of civilization throughout the Americas for thousands of years. The great civilizations of the Incas, Mayas, and Aztecs were founded on the cultivation of corn. Indeed, agriculture was at the very center of their religion. Corn was their life source, and they depended on the rain to make it grow. In the name of corn, the Aztec people sacrificed young women to two of their most important deities, the rain god, Tlaloc, and the corn goddess, Chicomecoatl.

Corn was also the staple grain of the North American Indians. They considered it a gift from their gods and referred to it as Sacred Mother. Many rituals were developed to summon the rain to ensure a good harvest. (Although corn is somewhat drought resistant during its last stages of growth, rain is essential during the reproductive tasseling stage when the silks emerge and the kernels begin to swell.) Native Americans called corn mahiz, which means our life.

It was once common belief that corn had been brought to the New World from Asia during prehistoric migrations. In 1950, anthropologists discovered fossilized wild corn pollen 200 feet below Mexico City. Radiocarbon dating determined that the pollen was 80,000 years old, predating the arrival of human beings in the Western Hemisphere and proving that corn was indigenous to the North American continent. Other expeditions during the 1950s unearthed tiny, half-inch ears of cultivated corn that were carbon-dated to as early as circa 5000 b.c.e.

It took centuries for corn to be carried north from Mexico by Native Americans migrating to what would later be the Four Corners region of New Mexico and Arizona. The appearance of corn in that region around 1200 b.c.e. contributed to a dramatic increase in population as corn farming was adopted in the Southwest. It took several centuries more for corn to reach Native Americans living in what would become the northeastern United States.

In the 15th century, the Spanish discovered that corn was grown by many Native American tribes throughout the Americas from the tip of South America to as far north as present-day Canada. Returning from a post in Cuba in 1492, a scouting party informed its leader, Christopher Columbus, that his maz could be baked, dried, and ground into flour. Within a few years, maize was introduced to Europe. From Spain, it spread to France, Italy, Germany, Austria, and Eastern Europe; the Portuguese took maize seeds with them on their travels to Africa, the East Indies, and Asia. By the late 16th century, corn was grown in many corners of the world.

The British colonists in Jamestown, Virginia, would have starved to death in 1607 if they hadnt planted corn under the guidance of Captain John Smith, who had procured seeds from the Powhatan tribe. Hoping to find gold when they arrived, Smiths colony finally found it in the corn they grew. The people of Jamestown were so successful with their corn harvests that by 1630 they were exporting corn to Massachusetts and the Caribbean. During the late 17th century, when legal currency was insufficient to meet public demand, the Corn Exchange Bank was established and corn kernels were used in lieu of money.

The Native Americans method of preserving maize under mounds of sand also saved the Pilgrims during their first winter in Massachusetts in 1620. When the Mayflower arrived at Plymouth, the Pilgrims were nearly devoid of supplies. Walking inland, they found a buried stash of corn, which not only fed them during that winter but also left them with enough kernels to plant in the spring. Learning from Native Americans, the settlers used corn in a variety of ways and, experimenting with the indigenous methods for making cornmeal breads, developed their own recipes.

Indian Wheat, of which there is three sorts, yellow, red, and blewis light of digestion, and the English make a kind of Loblolly of it to eat with Milk, which they call Sampe; they beat it in a Mortar, and sift the flower out of it; the remainder they call Homminey, which they put into a Pot of two or three Gallons with water and boyl it upon a gentle Fire till it be like a Hasty Pudden; they put of this into Milk, and eat it. Their bread also they make a Homminey so boyled, and mixe their Flower with it.