Contents

a SAVOR THE SOUTH cookbook

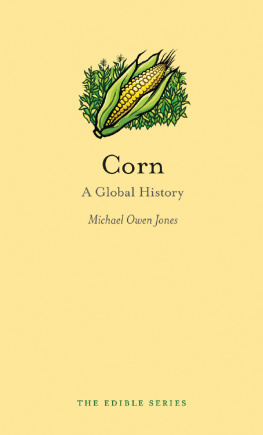

Corn

SAVOR THE SOUTH cookbooks

Corn, by Tema Flanagan (2017)

Fruit, by Nancie McDermott (2017)

Chicken, by Cynthia Graubart (2016)

Bacon, by Fred Thompson (2016)

Greens, by Thomas Head (2016)

Barbecue, by John Shelton Reed (2016)

Crabs and Oysters, by Bill Smith (2015)

Sunday Dinner, by Bridgette A. Lacy (2015)

Beans and Field Peas, by Sandra A. Gutierrez (2015)

Gumbo, by Dale Curry (2015)

Shrimp, by Jay Pierce (2015)

Catfish, by Paul and Angela Knipple (2015)

Sweet Potatoes, by April McGreger (2014)

Southern Holidays, by Debbie Moose (2014)

Okra, by Virginia Willis (2014)

Pickles and Preserves, by Andrea Weigl (2014)

Bourbon, by Kathleen Purvis (2013)

Biscuits, by Belinda Ellis (2013)

Tomatoes, by Miriam Rubin (2013)

Peaches, by Kelly Alexander (2013)

Pecans, by Kathleen Purvis (2012)

Buttermilk, by Debbie Moose (2012)

2017 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America.

SAVOR THE SOUTH is a registered trademark of the University of North Carolina Press, Inc.

Designed by Kimberly Bryant and set in Miller and Calluna Sans types by Rebecca Evans.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

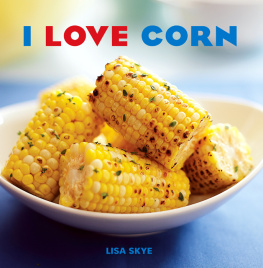

Cover photograph: istockphoto.com / YinYang

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Flanagan, Tema, author.

Title: Corn / Tema Flanagan.

Other titles: Savor the South cookbook.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2017] |

Series: A savor the South cookbook | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016036905 | ISBN 9781469631622 (cloth : alk. paper) |

ISBN 9781469631639 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Cooking (Corn) | Cooking, AmericanSouthern style. | LCGFT : Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX 809. M 2 F 54 2017 | DDC 641.6/315dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016036905

For John Patrick and John Silas, and for my family

Contents

SIDEBARS

a SAVOR THE SOUTH cookbook

Corn

Introduction

On every breakfast plate in the South there always appears a little white mound of food. Sometimes its ignored. Sometimes insulted. But without it, the sun wouldnt come up, the crops wouldnt grow, and most of us would lose our drawl.

So said Bill Neal in his Good Old Grits Cookbook (1991). And he was right, though in saying it he pointed to a larger truth. The fact is, without cornnot just gritsthe South would cease looking, sounding, and, most importantly, tasting like the South. The sun wouldnt come up. The crops wouldnt grow. And we would all most certainly lose our drawl.

Any good southerner can tell you just how important corn is to southern culture and cuisine. But corns siren call can be heard regardless of region, and that is especially true when it comes to corn-on-the-cob. There are few things on earth more satisfying than the crunchy, juicy sweetness of a fresh ear of corn, stripped of its silken sheath, plunged ever so briefly in boiling water, and dabbed with a little butter. As Garrison Keillor put it, People have tried and they have tried, but sex is not better than sweet corn. Theres no doubt that corn-on-the-cob is messy, delicious summertime fun.

Corn-on-the-cob may be the shining jewel on corns golden crown, but its just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the remarkable Zea mays. This oversized grass is capable of providing sustenance in an astonishing array of forms: as a fresh vegetable, dried grain, ground meal, legumelike hulled hominy, oil, and alcohol (not to mention the industrial additives and sweeteners that are now also wrought from it).

Corns versatility is the reason we get to indulge in everything from sweet corn chowder to handsomely browned cornbread, from soft corn tortillas to luxuriously creamy grits, and from crunchy caramel corn to a good, stiff bourbon drink on the rocks. That same versatility makes corn a year-round cooking companion. High summer calls for fresh corn eaten on the cob or shaved into salads, sauts, and soups, studding them with milky-sweet kernels. When fall and winter come, its time to make cornmeal biscuits, muffins, cobblers, and hotcakes, along with silky spoonbread and sausage-kissed cornbread stuffing. And the heaviest hitterscornbread and gritsare mainstays all year round. In one form or another, corn makes for good eating (and drinking) in every season, at any occasion, and at every time of day.

Corn-on-the-cob may be beloved everywhere, but when it comes to corn in its entiretyin all its many forms and fashionsI believe it must be best loved in the South. Where would southern cooking be without cornbread, grits, and hominy, for heavens sake? Indeed, corn has sustained southerners for generations, making southern cooking a natural and able guide to corns many culinary splendors. This cookbook is a testament to the place of corn in southern cooking, both throughout history and on the table today.

From Wild Grass to Maize

Corn is one of the few truly indigenous North American food crops. Not only are the genetic roots of the plant found on North American soil (in Central America, to be exact), but it was Native Americans who domesticated the plant thousands of years ago, long before European settlers made their way to the New World.

But where did corn come from, and what did it look like before it was shaped by human hands? For a long time, that remained a mystery, but we now know that corns genetic ancestor is a wild grass still in existence called teosinte. While the stalks and leaves are similar enough, teosintes grains bear little resemblance to the large, golden-kerneled cobs we know and love today. Teosintes seeds are much smaller and arranged in a slender stack that looks only vaguely like an ear of corn. And the grains themselves are nestled inside a rock-hard casing.

With teosintes grains locked up in armor, the plant would initially have had limited appeal as a grain. As Anthony Boutard reports in his book Beautiful Corn (2012), it likely first captured the attention of the hunter-gatherers of Central America not for the seeds but for the sugar that ran through its veins. Like sugarcane and sorghum, teosintes stalks could be chewed to release a sweet nectar. While tasty, the sugars in the grass were nowhere near nutritious enough to bear the weight of a civilizations growth. So it wasnt until the grains were unlocked that corn became the life-sustaining staple it remains today.

In that regard, corns early domesticators likely had a little help. It is thought that the domestication process started with a genetic mistake: a mutation that caused teosinte to produce naked kernels, without the hard shell. Early Native American farmers slowly isolated and bred the plants with naked kernels and other desirable traits. After hundredsif not thousandsof years, the result was an entirely new creation: maize (from the Arawak mahiz).

Starting in present-day Central America, indigenous peoples brought maize (in breathtakingly diverse variety) with them as they migrated north, into the borders of what is now the United States. So diverse was the plant at this time that it was capable of growing in just about any climate and altitude. On the east coast of the United States, where European settlers would eventually make landfall, hard-kerneled, flint-type corn predominated in the north, while softer, starchier, dent-type corn made its home in the South (more on that later).