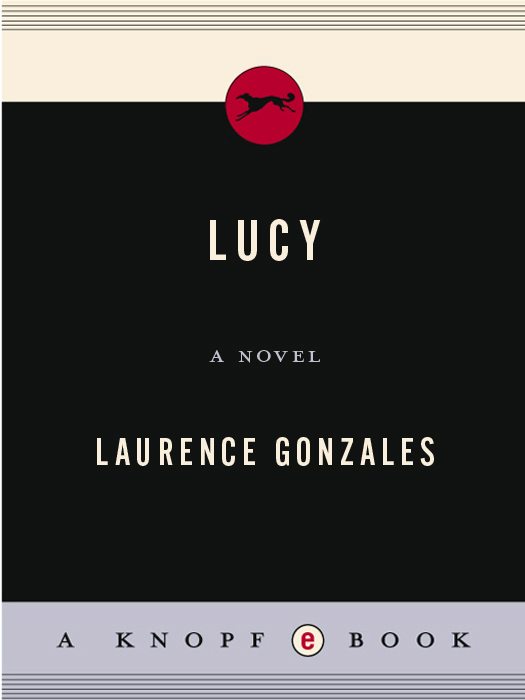

ALSO BY LAURENCE GONZALES

Everyday Survival

Deep Survival

The Heros Apprentice

One Zero Charlie

The Still Point

Artificial Horizon

El Vago

The Last Deal

Jambeaux

This book is dedicated to my children

Elena, Amelia, and Jonas

Contents

beauty remains, even in misfortune.

ANNE FRANK, age fourteen

1

JENNY WOKE TO THUNDER . There was no light yet. She reached into the darkness and found a tin of wooden matches on the ammunition case beside her bed. She selected one and struck it on the case. The flame flared red then yellow and sulfurous smoke rose. Newborn shadows danced on the walls of the hut. She touched the match to the wick of a candle and a light grew up from it like a yellow flower tinged with blue. Smoke hung in the still wet air. The interior of the hut seemed at once bare and cluttered. The walls were unpainted board, the floor was buckled plywood. Against one wall was a crude desk made out of a door, a few photographs tacked to the wall above it: Her mother at home near Chicago. Snapshots of the bonobos. Her friend Donna with the bonobos at the zoo.

Jenny swung her feet to the floor and listened. Shed heard the hissing of the rain all night. But now another sound had crept in. She pulled on her boots and stood, tall and tan and rangy in the yellow light. She ran her hand through her sandy hair and secured it carelessly behind her head.

She heard the sound again: Thunder. But now she heard the metallic overtones as the report echoed up into the hills, then returned. As she grew more awake Jenny realized that she was hearing guns. Big guns. The Congolese insurgents were firing rocket-propelled grenades. It had been a calculated risk for her to be here. But she had found the beautiful great apes known as bonobos irresistible. Year after year she had returned despite the danger. The fighting had flared and died down and flared up again for more than a decade and a half. Now the civil war had begun in earnest and she had to leave immediately. Her old friend David Meece at the British embassy in Kinshasa had warned her in no uncertain terms: You have no value and so they will kill you. When the shooting starts, go to the river as quickly as you can.

A whistling overhead. Another charge of metallic thunder. The concussion shook the pots above the camp stove. She heard answering fire from another direction.

She had expected to have more warning, an hour, half an hour. But they were upon her. She grabbed a flashlight, the machete, and the backpack that she kept ready for travel. She picked up a bottle that was half full of water and drank it in one long bubbling draught. Gasping for air she picked up a full bottle and clipped it to her belt.

She stepped out the door and into the clearing. She knew that entering the forest at night was a risk, but staying would be worse. She looked back at her hut and felt a rush of sadness, even as her pulse pounded in her neck. Then she turned and ran toward the forest, feeling the water sway uncomfortably in her gut.

The rain had stopped. The jungle before her was black and glistening in the flashlight beam. She had promised herself that she would make an effort to reach the British researcher, Donald Stone, whose observation post was on the way to the river. He had been courteous enough the few times shed seen him. But their camps were far enough away that it had made dropping in for a casual visit impractical. All she knew was that he was studying bonobos, too, but didnt seem to want to collaborate. Nevertheless, Jenny had decided to do her best to help him if it ever came to that. Shed heard that he had a daughter and if so Well, this was no place for a child.

As she loped through the forest along familiar paths, she heard the low thump of a mortar, the whistling of the shell, then the steely shock of another explosion to the east. She smelled smoke. Then came the sporadic firing of automatic weapons.

As she hurried on, the first light of day began to penetrate the forest canopy. She switched off her flashlight and let her eyes adjust. Another shell went off and she ran ahead. Think, think: What was next? Check on Donald Stone. Then get to the river. If she could find someone with a radio, David would help. If he was still there. If the embassy was still standing. If, if, if.

She ran on through the day, following the one broad path that she knew led in the direction of Stones camp. She was concerned for the bonobos. They were amazingly strong yet paradoxically delicate creatures. The shock of loud noises could kill them. On the other hand, they were smart. Theyd be miles away by now in the tops of the trees. Sometimes it seemed to Jenny that they were almost human. In graduate school in 1987 she had gone to work with the largest population of bonobos in captivity at the Milwaukee Zoo. They were among the last of the great apes. The first time Jenny had locked eyes with the dominant female at the zoo, she knew that she was looking at a creature who was far more like her than unlike her. Whenever she wasnt working, shed spend hours watching the bonobos. But once shed gone to Congo to see them in the wild she knew where she belonged.

At a bend in the trail, she stopped to listen. The shelling seemed to have moved off to the east. She swatted at the flies and mosquitoes around her face. Sweat had soaked her shirt and was dripping from her scalp into her eyes. She wrapped a bandanna around her head and pressed on. Then a brief but intense rainstorm drenched her and she resigned herself to being wet. At least it had knocked the insects down.

She desperately wanted to rest, but as night fell she took a headlamp from her pack and kept on going. All night long she heard the fighting fade, then move closer, then fade again. Twice in the night she smelled the smoke.

Morning came slowly. A mist began to rise. The path narrowed, and she knew that soon she would see Stones camp. Shed been there only twice before. On both occasions shed suggested that they work together, but Stone had politely pointed out that he had a feeding station for the bonobos while Jenny did not. The two approaches to research were incompatible. She had let it go. She was too busy with her own work to worry about his.

Jenny stopped running so abruptly that she tottered back and forth like a weighted doll. At first she thought she was looking at a twisted branch. Only nownow that her body had stopped without her consentdid she realize that it was a dark brown forest cobra perhaps a meter in length. It was coiled loosely along a branch holding its head high. She remembered what the toxicologist at the university had told her the first time she came to Congo: If you encounter one of these in the wild, dont breathe. They read your carbon dioxide signature. If youre bitten by one a kilometer from home dont bother running: You will die. And youll be conscious the whole time while the venom gradually paralyzes you until your diaphragm stops working.

Jenny began a Tai Chi move, shifting her weight as slowly as she could. She moved back by centimeters. A minute passed. Two minutes. She had moved back only a foot or so when a shell landed. The cobra seemed to startle at the noise. It dropped to the ground and shot off into the undergrowth like a stroke of dark lightning flowing to the earth.