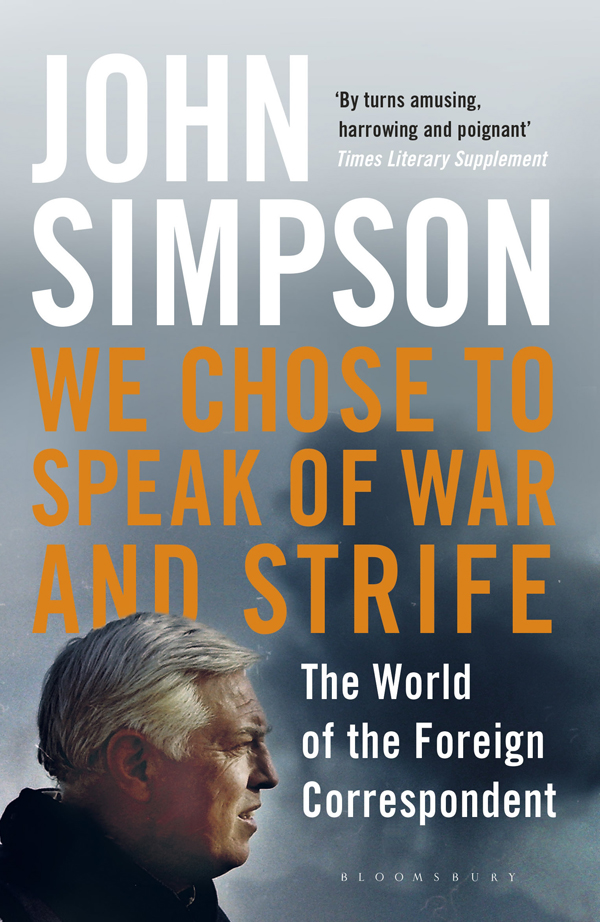

A NOTE ON THE AUTHOR

JOHN SIMPSON is the BBCs World Affairs Editor. In a BBC career spanning fifty years he has reported on major world events from all corners of the globe, and was made a CBE in the Gulf War honours list in 1991. He has twice been the Royal Television Societys Journalist of the Year, and has won three BAFTAs, the News and Current Affairs award in 2000 for his coverage, with the BBC News team, of the Kosovo conflict, and, in 2001, an Emmy for his report on the fall of Kabul. He has written four bestselling volumes of autobiography: Strange Places, Questionable People; A Mad World, My Masters; News from No Mans Land and, more recently, Not Quite Worlds End. He lives in Oxford.

To Rafe, who is to me what Du Fus son was to him:

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Strange Places, Questionable People

A Mad World, My Masters

Days From a Different World

Not Quite Worlds End

News from No Mans Land

The Wars Against Saddam

Unreliable Sources

WE CHOSE TO SPEAK OF WAR AND STRIFE

The World of the Foreign Correspondent

John Simpson

CONTENTS

MEMORIAL

We spoke, we chose to speak of war and strife

a task a fine ambition sought

and some might say, who shared our work, our life:

that praise was dearly bought.

Drivers, interpreters, these were our friends.

These we loved. These we were trusted by.

The shocked hand wipes the blood across the lens.

The lens looks to the sky.

Most died by mischance. Some seemed honour-bound

to take the lonely, peerless track

conceiving danger as a testing ground

to which they must go back

till the tongue fell silent and they crossed

beyond the realm of time and fear.

Death waved them through the checkpoint. They were lost.

All have their story here.

James Fenton

[Ms Merritt and Ms Lloyd-Roberts at the headquarters of the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity]

Lloyd-Roberts: Good morning, my name is Sue Lloyd-Roberts, Im here from the BBC and this is Mary Merritt, a former Magdalene Laundry worker.

Unidentified representative of the order: Youve already sent in a request and I think youve got your answer to that request.

Lloyd-Roberts: No, weve been refused an interview but we have some very important questions to ask.

Transcript from BBC Newsnight, September 2014

You could see right from the start that it wasnt going to be the usual kind of commemoration service. People trooped in quietly and sat down, without saying much to each other. Often these media gatherings are a chance for everyone to talk loudly and show off, and maybe score a point or two off someone else. Here, though, the mood was different. Nashs masterpiece, All Souls, Langham Place was as full as Id ever seen it for an occasion like this, but normally there would be an expectant buzz of conversation, almost an enjoyment about the whole thing, as though it was part of a last performance by the person we were commemorating. There would be a sort of half-expectation that they might come on stage soon, the same as ever, and cheer us all up and give us something to laugh about.

Ive been to plenty of memorial services like this, and I hope that one day therell be one for me that people will sing the hymns loudly and enthusiastically, and laugh at the reminiscences of the hare-brained things Ive done, then troop out in jolly mood at the end, clapping each other on the back and saying, Fancy a spot of lunch somewhere? That, after all, is the finest way to be remembered: with affection and amusement, in an atmosphere of camaraderie.

The service for Sue Lloyd-Roberts wasnt like that at all. She had died of leukaemia at the age of sixty-four, at the height of her powers, as beautiful and witty and spikily charming as she had been when I first met her, thirty years earlier. No one in All Souls can have felt that this was a life which had reached its logical, dignified end. On the contrary, everyone must have felt a sense of unfairness, of potential not fully realised, of personal loss. When the last strains of a song Sue had loved, Bye-bye Miss American Pie, had faded away, and the congregation was standing up reluctantly to leave, my wife, who had known Sue as well as I did, turned to me with her eyes full of tears and said, I dont want to talk to anyone. I felt the same. We actually did have a lunch to go to, but when we got to the restaurant we both found it hard to shake off the sense of gloom that hung over us. One of the sunniest people either of us had ever known had been taken out of our lives.

Sue was born in 1950, and never entirely lost the cut-glass accent (modified by a delightful lisp) which she learned at home in Belgravia and at Cheltenham Ladies College. She went on to St Hildas, Oxford, where she worked on the student magazine Isis with Tony Hall, the future director-general of the BBC. She was a lifelong socialist, and always maintained an unshakeable sympathy with the underdog. Throughout her career, first at Independent Television News and then at the BBC, she did some of her very best reporting on human rights issues, from the Soviet bloc in the 1970s to Burma in the 2010s.

Thereve been too many untimely deaths in recent years. Among others, Marie Colvin of the Sunday Times; John Harrison, John Schofield, Kate Peyton, Brian Hanrahan and Brian Barron of the BBC; Terry Lloyd and Gaby Rado of ITN; James Forlong of Sky News; Rick Beeston of The Times; Daniel Pearl, James Foley, Steven Sotloff: all died at the height of their powers, killed by disease or violence or accident or the pressure of the job, and the friends and admirers who went to services of commemoration for them felt very much the same as those who went to the one for Sue Lloyd-Roberts.

Still, other things being equal, foreign correspondents tend to live at least as long as any other section of the community, and by no means all commemorations are gloomy affairs. Sir Charles Wheeler died, full of honours, in 2008 at the age of eighty-five. Dick Beeston of the Daily Telegraph, the father of Rick, died at eighty-eight. The man whos generally regarded as the founder of the profession, William Howard Russell, was eighty-six when he died, having reported on the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny, the American Civil War and the Franco-Prussian War. Martha Gellhorn, who smuggled herself onto a hospital ship in order to reach the D-Day beaches, ended her life peacefully in Chelsea at the age of eighty-eight; only a year or so before, she had visited Brazil to write an article on the murder of street children by the police. Clare Hollingworth of the Daily Telegraph and the Guardian, who reported from the Polish border on the outbreak of the Second World War, is 104 at the time of writing and, though very frail, still turns up most days at the Foreign Correspondents Club in Hong Kong. Not every foreign correspondent, fortunately, dies before their time. Even Nathaniel Butter, the great-great-grandfather of British journalism, whose story appears in the next chapter, lived to be eighty-one, dying in 1664.

This book is intended to be various things: in particular, an affectionate celebration of a trade which, I fear, is on its way out. I would also like to think that over the course of the stories I tell in the following pages it will constitute a kind of guidebook to the origin, development and practice of the foreign correspondents profession. What it isnt, is an exhaustive history. I have followed the advice of Lytton Strachey in his bitchy but influential book