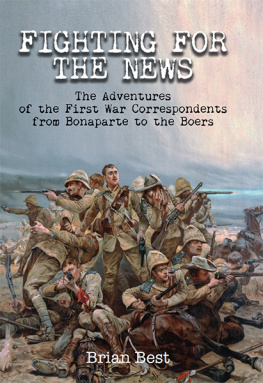

FIGHTING FOR THE NEWS

The Adventures of the First War Correspondents from Bonaparte to the Boers

This edition published in 2016 by Frontline Books, an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS.

Copyright Brian Best, 2016

The right of Brian Best to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-437-4

PDF ISBN: 978-1-84832-440-4

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84832-439-8

PRC ISBN: 978-1-84832-438-1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in 10.5/13 point Palatino

For more information on our books, please email:

,

write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

Contents

Introduction

I t is now two centuries since a newspaper conceived the idea of sending a reporter overseas to observe, gather information and write about war. With no experience to draw upon, both newspaper and correspondent gradually worked out a procedure that has evolved into todays incredibly sophisticated form.

Mans fascination with wars is as old as war itself. Memoirs and first-hand accounts have always found a ready public from the time of Ancient Greece. Until printed books became available, tales of warfare were imparted by storytellers and minstrels. Even today there are parts of the world beyond the reach of television and newspapers where the storyteller still relates tales of old battles as though they were only recently fought. On the route of Alexander the Great, for instance, the storyteller still recounts to the inhabitants of some remote village the battles fought during the Greek conquest.

With Johann Gutenbergs invention of the moveable-type press in 1456 and its development over the following centuries, a literate public could have access to current information. Thus the daily newspaper began to evolve. By the early nineteenth century there was a need for more accurate and immediate reporting of overseas events, particularly the exploits of Napoleon Bonaparte, the man who dominated European affairs for so long.

At first, newspapers relied on the accounts of serving army officers. The problem with accepting a soldiers version of war was that it was couched in favour of the soldiers own institution, limited in its view of the larger picture and unlikely to give any insight into the realities of war. For overseas news, the newspapers also relied on accounts from diplomats, travellers and sailors, as well as government bulletins, which were often published long after the event.

It was The Times that led the way, as it has so often done, with the employment of the first special overseas correspondent. This undertaking was to cover the Napoleonic Wars and, although not altogether successful, it created enough interest for the experiment to be repeated in later conflicts. At the high water mark of Victorian power, Specials were the stars of journalism, and what they wrote sold newspapers. The reports of William Russell and Archibald Forbes markedly increased the circulation of both The Times and the Daily News. Russells reports from the Crimean War are credited with bringing down Lord Aberdeens Government and an improvement, however marginal, in the conditions of the ordinary soldier. George Steevenss accounts from the Sudan put the infant Daily Mail and its proprietor, Alfred Harmsworth, on the road to success. The artist reporters like Melton Prior and Frederic Villiers brought great success to The Illustrated London News and The Graphic respectively and, even today, their drawings are still used to embody the steadfast British Tommy holding back the heathen hordes.

Photography, which started in the Crimean War, became increasingly used as the century progressed. By the Boer War, cinematography began to be employed despite the clumsy equipment.

The military establishment hated this new phenomenon as they were now open to public scrutiny. Unwieldy and bureaucratic, the military were slow to control the specials, who were free to wander the camps, picking up scraps of information and gossip. They became close observers of fighting and critics of incompetent commanders. Rather than try to embrace this new breed in order to influence what was written, the military establishment sullenly tolerated newsmen because their political masters ordered they should do so. By the end of the century, thanks almost entirely to Lord Kitchener, the beginnings of censorship began to hamstring this freedom and, by the First World War, the Golden Age was a faded memory.

These war reporters were a tough and resourceful band, whose adventures made a read as exciting as the wars they reported. They were often physically unprepossessing, being overweight and balding like Melton Prior, or short and elderly like Frederic Villiers, who was still travelling to wars into his late seventies. Appearances, however, could be deceptive, for both Prior and Villiers had enormous reserves of grit and determination which overcame any physical shortcoming. Pioneers like Russell and Archibald Forbes, had to learn as they went along. Without backup teams and shunned by the military, they had to provide for themselves. Armed with little more than writing materials, a bag of sovereigns and a revolver, these men had to rely on their guile and stamina to obtain their news. Most were excellent horsemen and they thought little of riding 100 miles to reach the nearest telegraph, filing their report and then riding back to the fighting. With their flamboyant quasi-military garb, often displaying foreign medal ribbons, they cut dashing figures. It is small wonder that they attracted adventure-seeking young men to their ranks; men like Frank Power and Hubert Howard, both destined to die in the Sudan on their first assignments.

The Victorian Specials saw themselves not only as viewers of war but also participants, acting with the same patriotism and heroism as the soldiers. In order to get good stories, they had to be close to the fighting and many were killed or wounded trying to achieve the scoop. They also took risks in getting their stories back to their papers ahead of their rivals. In spite of the competition, there was a camaraderie fostered by common dangers and hardships, often resulting in the sharing of resources and services.

This Golden Age was short-lived as set-piece battles became a thing of the past. The twentieth century dawned with the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War, a new style of conflict with fighting that covered vast areas. Now newspapers sent teams of reporters and, although they still enjoyed freedom of movement, censorship was starting to restrict freedom of writing. There were still plenty of the old school of Specials around, but scoop-hungry new men like Edgar Wallace were imposing themselves. The demise of the glamorous swashbuckling correspondent began in earnest during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, when the Japanese employed a most effective censorship which acted as a model for the British during the First World War.

In 1914, after initially trying to seek and report the truth, newspapers effectively became part of the government propaganda machine. By choosing to boost morale on the Home Front and give all support to the military leaders, costly blunders and horrific casualties were glossed over or concealed. The reporters were generally decent men who managed to convince themselves that compromising their calling in the name of patriotism was the right thing to do. Some, like Philip Gibbs and William Beach Thomas, later wrote of their shame and remorse for misleading the public. The public and the common soldier, however, were in no mood to forgive, and reporters were held in low esteem for many years after the war.

Next page