At various times, Benigno Aguirre, Ronet Bachman, John Barnshaw, Joan Best, Peter Blum, Anne Bowler, Gerald Bracey, Spencer Cahill, Karen Cerulo, Joan DelFattore, Gary Alan Fine, David Grazian, Robert Hampel, Philip Jenkins, Aaron Kupchik, Kathe Lowney, Brian Newby, Larry Nichols, David Schweingruber, and Rhys Williams made helpful comments on various versions of this work.

I also want to thank the people at the University of California Pressespecially Naomi Schneider and Dore Brownfor once again shepherding my work into print. Ellen F. Smith, the copy-editor, was especially helpful.

CHAPTER ONE

LIFE IN AN ERA

OF STATUS ABUNDANCE

I live surrounded by excellence. On a drive to our local shopping center, I find myself behind an SUV with a bumper sticker declaring the driver's pride in being the parent of a middle-school honor roll student. In the parking lot, I wind up next to a car bearing a red, white, and blue magnetic ribbon that says, U.S.A.-#1. Several of the storefronts in the shopping center sport banners or other signs reporting that the stores have received statewide honors. I live in a small state, and I realize that it must be easier to be designated the Bestin Delaware than it would be elsewhere. Still, these signs tell me that our small shopping center contains a remarkable number of establishments that have been designated as offering outstanding services (our state's best preschool and its best veterinarian) or for selling terrific merchandise (Delaware's best Chinese take-out and burgers). The sandwich shop has a wall covered with framed certificates declaring that it has won various awards for serving the state's best cheesesteaks, hoagies, deli, etc., etc. Before the video store closed, it was filled with DVD boxes identifying movies that had received Oscars, film festival awards, or at the least two thumbs up. At the newsstand, I can find magazines rating the best colleges, hospitals, high schools, employers, places to live, places to retire, and on and on. The party store features an Award Center rack with an array of colored ribbons that can be awarded to a Good Eater, a Star Singer, or someone who has turned fifty or is having some other birthday evenly divisible by ten. Back home, when I log onto my computer, my university's home page features today's news items, a large share of which report that some professor or student on our campus has won a prize. And so on. Several times each day, I encounter claims that someone has been designated excellent by somebody else.

The fact that some third party has made these designations is key. If I own a pizza parlor and put up a sign declaring that I bake the best pizzas around, most customers will be skeptical of my self-serving claims. But, if after counting the ballots submitted by their readers, Delaware Today magazine or the Wilmington News Journal newspaper identifies the best pizza in Delaware, that information somehow seems a little more convincing, and a merchant who displays a banner announcing such an award seems to be doing more than just bragging. Somebody elsesome third party, whether it's expert judges or just whoever responded to some pollhas vouched for the excellence of this hamburger, that preschool, or whatever.

We pass out praise and superlatives freely. Americans have a global reputation for being full of ourselves. We chant, U.S.A.Number One! U.S.A.Number One! We confidently describe our country as the world's greatest, its sole superpower. But self-congratulation is far more than a matter of national pride. It is a theme that runs throughout our contemporary society.

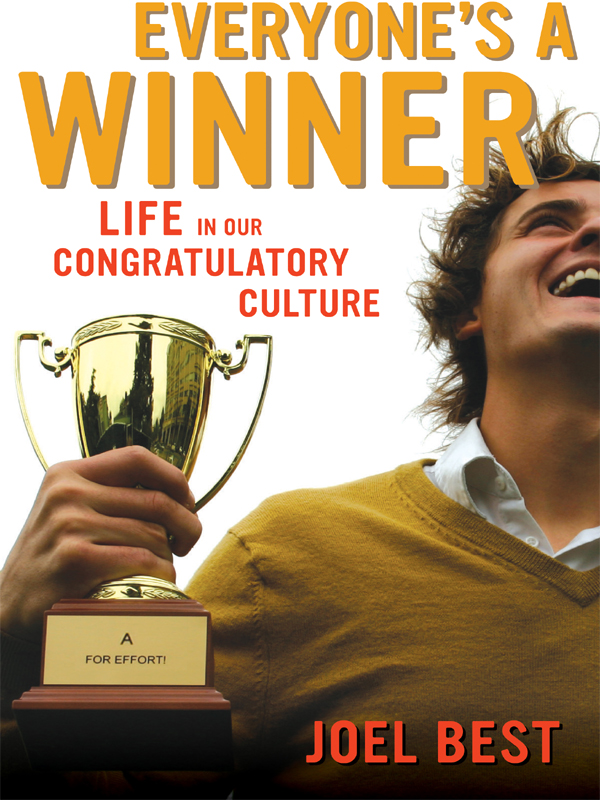

The kudos begin early. These days, completing elementary school, kindergarten, even preschool may involve a graduation ceremony, complete with caps and gowns. Many children receive a trophy each time they participate in an organized sports program, beginning with kindergarten soccer or T-ball, so that lots of third graders have already accumulated a dresser-top full of athletic trophies. Many elementary school classrooms anoint a Student of the Week. Experts justify this praise by arguing that children benefit from encouragement, positive reinforcement, or warm fuzzies. As the commentator Michael Barone sees it: From ages six to eighteen Americans live mostly in what I call Soft Americathe parts of our country where there is little competition and accountability. Soft America coddles: our schools, seeking to instill self-esteem, ban tag and dodgeball, and promote just about anyone who shows up.

But children aren't the only beneficiaries of our self-congratulatory culture. Awards, prizes, and honors go to adultsand to companies, communities, and other organizationsin ever-increasing numbers. It is remarkable how much of our news coverage concerns Nobel Prizes, Academy Awards, and other designations of excellence. And, at the end of life, obituaries often highlight the deceased's honors (Bancroft Dies at 73. Won Oscar, Emmy, Tony). Congratulatory culture extends nearly from the cradle to the grave.

This isn't how we like to think of ourselves. Michael Barone insists: From ages eighteen to thirty Americans live mostly in Hard Americathe parts of American life subject to competition and accountability. Hard America plays for keeps: the private sector fires people when profits fall, and the military trains under live fire. easily. There is stiff competition, and only the best survive and thrive. This vision begins American history with no-nonsense Puritans whose God expected them to work hard and receive their rewards in heaven. People were to live steady lives and gain the quiet admiration of others for their steadfast characters. Pride was one of the seven deadly sins. In this view, our contemporary readiness to praiseand to celebrate our own (or at least our middle schoolers) accomplishmentsseems to be something new.