Europe today is a powder keg and the leaders are like men smoking in an

arsenalA single spark will set off an explosion that will consume us all

I cannot tell you when that explosion will occur, but I can tell you where

Some damned foolish thing in the Balkans will set it off.

Otto Bismarck at the Congress of Berlin 1878

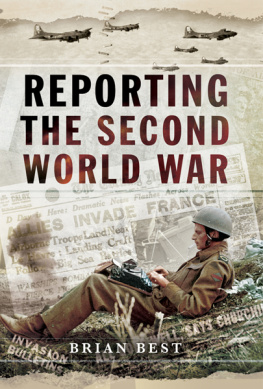

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

PEN AND SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Brian Best, 2014

ISBN 978 1 47382 117 0

The right of Brian Best to be identified

as the author of this work has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in Times by CHIC GRAPHICS

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family history, Pen & Sword Maritime,

Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local history,

Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When,

The Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

In researching this book many hours were spent in libraries and archives, notably the British Library and the British Newspaper Archive, where the staff were unfailingly helpful. The Times Archive, now banished to the northern outskirts of London, was a particularly fruitful source for information and I am grateful to Anne Jensen for her knowledge and help. My special thanks, however, are reserved for Sally Baker, formerly of The Times, who volunteered to proof read and edit my manuscript, turning my offering into readable prose for which the reader will be grateful. Thanks also to Irene Moore from Pen & Sword.

Finally, thanks to Michael Clayton, a former BBC correspondent from the wars of Vietnam, Cambodia and the Middle East, whose advice was eagerly accepted and who has kindly contributed the Forward.

Foreword

It has been truly said that truth is the first casualty in war. In both world wars it was standard practice for the military top brass on all sides to manipulate coverage of the conflict in the media.

However, the role of the war correspondent in the First World War was distorted to a scandalous extent. The British Government and the military top brass relied on jingoism and news management to ensure a ready supply of recruits for a war whose very cause is still a subject of confusion and debate.

Having reported something of battles in Vietnam, Cambodia and the Middle East I am well aware that media coverage remains a military headache, but in the Great War managed news eventually led to cynicism at home and encouraged mutiny among troops on all sides.

When conscription became necessary to reinforce mightily the British Expeditionary Force after catastrophic early losses, it was deemed even more necessary to keep the full truth about trench warfare from the public at home.

Brian Best has performed a considerable service in describing the 191418 war from the viewpoint of correspondents who were at first forbidden even to visit the front line. Taking unauthorised pictures of battle was punishable by a firing squad.

Correspondents worked under excruciating censorship and other pressures from the senior military and politicians. Only years later did some correspondents write truthfully of what they had seen and apologise for their reports during the war. Many of their published accounts were so distorted that correspondents were often despised by those serving in the trenches.

Brian Best rightly apportions considerable blame to the newspaper proprietors. he is fair in emphasising the work of a few correspondents who were prepared to buck the system, and produced truthful reports, especially from the disastrous Gallipoli campaign. his narrative of the Great War through the press coverage which helped to prolong it provides a clear guide to the conflict from an important aspect often overlooked.

This is a fascinating contribution to 191418 literature offering valuable lessons on the conduct of war reporting which are still relevant.

Michael Clayton

Prologue

With the passing of the Victorian age, so also passed the so-called Golden Age of war reporting. In a period of about fifty years, stretching from the Crimean War to the Second Anglo-Boer War, the specials, as the war reporters were known, enjoyed a freedom and popularity which made them the stars of their newspapers. It was a time when war reporting actually sold newspapers. Often armed with little more than a bag of sovereigns, a notebook and a revolver, the special was free to wander the battlefield and, in some cases, become involved in the fighting.

In the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny, it was William Howard Russell of The Times who inspired other adventurous spirits with a literary bent. Men like Archibald Forbes of the Daily News, who rode 110 miles in 20 hours through enemy-infested territory to be the first to file the news of the Zulus defeat at Ulundi in 1879. This kind of determination to be first with the news began to sow the seeds of resentment among many senior military officers who felt that their triumphs were being trumped by the newspapers.

General Sir Garnet Wolseley, who benefitted from exposure by the press, confided in his wife: Confound all this breed of vermin Shall I never be strong enough to be honest and tell these penny-a-liners how I loath them and their horrid trade.

One officer in particular harboured a visceral hatred of the press and for over fifteen years did all he could to keep reporters away from the action and force them to report only what suited the army. he was Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, Lord Kitchener of Khartoum. During the Sudan War of 1898, he famously snapped at a group of reporters standing outside his tent: Get out of my way, you drunken swabs. he also imposed a news blackout which foreshadowed what was to come.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the war correspondent could still accompany the army on minor expeditions but increasingly had to adhere to guidelines that did not allow the reporting of poor morale, bad conditions for the troops or cruelty towards the native population.

The final fling before the curtain came down for ever was the Balkan War of 191213. This heralded the descent into the horrors of the Great War. For the war correspondent it saw the end of freedom to write reports on what he had seen in the name of patriotism. It effect, war correspondents evolved into the mouthpiece of the military, enjoying the flattery they received from the generals, wearing smart uniforms and turning a blind eye to the reality of what the ordinary soldier endured. In doing so, they turned what had been a noble profession into one to be reviled.

After the First World War most of them had pangs of conscience and wrote books about their part in the war with a genuine regret that they had masked the truth. It was to be many years before the public and, more particularly, servicemen would believe what was published in the newspapers.

Next page