In tendering thanks, let me begin by rounding up the usual suspects: libraries whose courtesy and friends whose unsparing kindness made this book better than it could have been otherwise. In every archive, the staff worked diligently and energetically to roust out materials that I needed, though, as ever, those running the manuscripts division in the Library of Congress did the most, and with patience and humor. As usual, my chums at the University of Kentucky were trumps. Among those who pored over the chapters and red-penciled purple prose were Jeremy Popkin, Thomas Cogswell, David Hamilton, and David Olster. Besides some shrewd suggestions for ways that the manuscript might expand its focus, Jeremy did what he could to shorten the final work substantially. William R. Childs, at Ohio State, made more sense in his comments than much of the writing he was criticizing, and out at Arizona State, Brooks Simpson applied his expertise on General Grants career to that particular chapter. Still more let me hail Donald Ritchie, whose book on a similar subject might have made him incline to behave as a competitor. Instead, he welcomed the company; many short hours we spent swapping stories about the press gang and treating the reporters with all the cynicism they bestowed on public officials. His glance at the manuscript left it improved in quite significant ways. My appreciation for the painstaking copyediting of Stevie Champion goes beyond words.

A very different debt I owe to my dear wife, Susan Liddle, who let me rant about whole mobs of journalists as if they really existed, and to Ariel, who more than once reorganized the whole work by pushing the pile of pages onto the floor, a summary judgment which some critics may think the best of any. And finally, of course, my thanks go to my parents, Clyde and Evelyn Summers, the smartest, most thorough, and best editors of all. Their mark lies on every page of the finished manuscript.

Reporters Initials & Pseudonyms

Agate Whitelaw Reid, Cincinnati Gazette

Creighton R. W. C. Mitchell, Danbury News

Data W. W. Warden, Baltimore Sun and New York Times

Dixon Sidney Andrews, Boston Daily Advertiser

D. P. Donn Piatt, Cincinnati Commercial and Enquirer

Gath George Alfred Townsend, Chicago Tribune

and New York Graphic

G. G. Grace Greenwood, New York Tribune

Gideon W. S. Walker, Chicago Times

H. J. R. Hiram J. Ramsdell, Cincinnati Commercial

H. V. B. Henry Van Ness Boynton, Cincinnati Gazette

H. V. N. B. Henry Van Ness Boynton

H. V. R. Horace V. Redfield, Cincinnati Commercial

Laertes George Alfred Townsend, New York Graphic

M. C. A. Mary Clemmer Ames, New York Independent

Mack Joseph B. McCullagh, Cincinnati Commercial

Mrs. Grundy Austine Snead, Washington Sunday Capital

Nestor William B. Shaw, Boston Transcript

Observer R. J. Hinton, Worcester Spy

Occasional John Wien Forney, Washington Chronicle

Olivia Emily Edson Briggs, Philadelphia Press

Perley Ben: Perley Poore, Boston Morning Journal

Warrington W. S. Robinson, Springfield Republican

Z.L.W. Zebulon L. White, New York Tribune

THE PRESS GANG

Introduction

You are they

That search into the secrets of the time,

And under feignd names, on the stage

present

Actions not to be touchd at; and traduce

Persons of rank and quality of both

sexes,

And, with satirical and bitter jests,

Make even the senators ridiculous

To the plebeians.

Philip Massinger, The Roman Actor, 1630

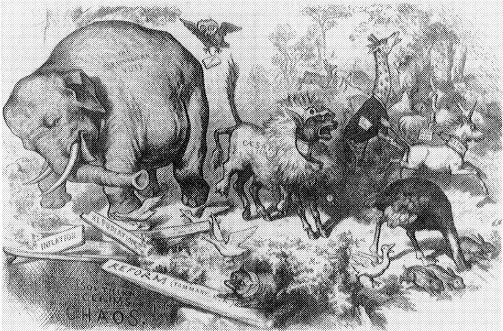

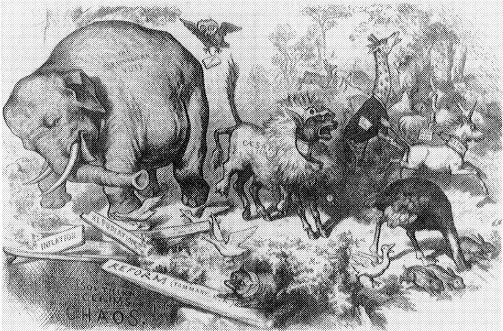

The Third-Term Panic (Thomas Nast, Harpers Weekly, November 7, 1874).

The cartoon from late 1874 is one of Thomas Nasts most famous: barely concealed in a lions skin called Caesarism, a donkey brays and panics the animals of the woodsa monocled unicorn, a frantic giraffe, an owl, and most conspicuously, in its first appearance as a symbol, a Republican elephant stampeding into the political abyss. But why make the New York Times a unicorn? Or the New York Tribune a giraffe, or the World an owl dropping an arithmetic book?

Nasts cartoon, in fact, is a comment on the so-called press gang of his age, and his better-read readers might have grasped the point of his symbols at once. They would have known that the Times was edited by the Englishman Louis J. Jennings; what better beast than one from the British coat of arms? Anyone familiar with Nasts caricatures would connect World proprietor Manton Marbles nose and the beak of a bird of prey; anyone familiar with Marbles editorials would appreciate his reliance on statistics to make his points for free trade or to change a setback for Democratic candidates into a victory. As for the Tribune, the so-called tall tower of its unfinished office building was as conspicuous on Printing-House Square as a giraffes neck, and it just may have been Nasts inspiration.

The fact that all these allusions might be second nature to Nasts audience and not to later historians should give us pause. Rare is the artist today who would feature a newspaper, much less an editors face, in his cartoon, but in the 1870s the caricaturist poked fun at journalists on a regular basis. Even in cartoons where politicians took center stage, newspapermen often showed up in the background, observing, commenting, or just swelling a crowd. Clearly, something was significantly different about the role that the press played in politics, different perhaps from earlier times and certainly from our own.

This book is about that difference and its consequences for the making of policy. It is a study of professional journalism fresh out of the eggshell, just as it is discovering itself as a profession and before it has established standards of conduct and freed itself from the legacy of the past, a legacy of political engagement. It is the story of the independents attempt to turn that legacy to new ends: the political engagement of the outsider, with editors playing the role of Thersites, commenting on the flawed nature of the generals. And it is, in the end, a story of failure, a war with the politicians that the politicians, or at least politics, won.