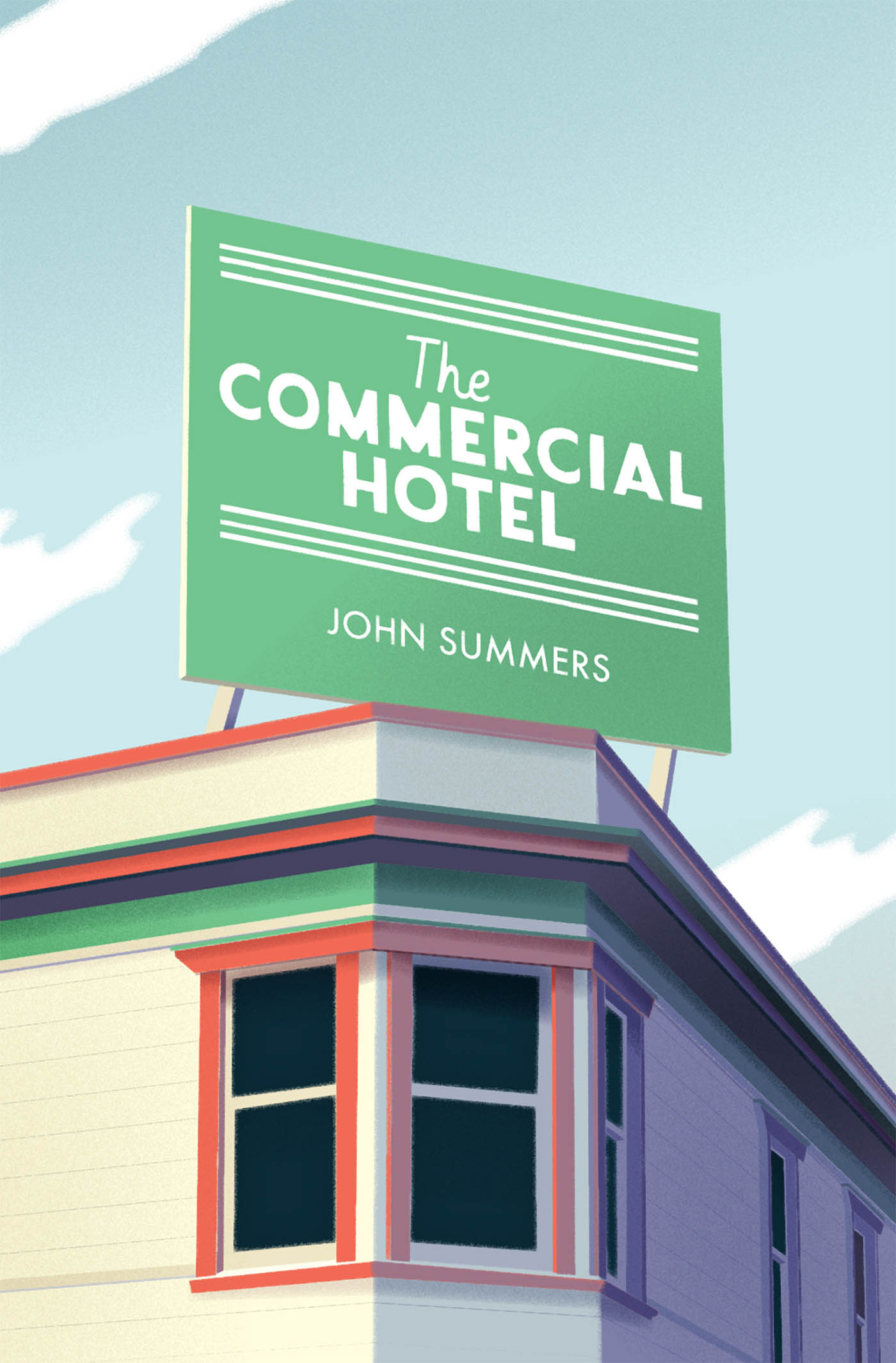

Victoria University of Wellington Press

PO Box 600 Wellington

New Zealand

vup.wgtn.ac.nz

Copyright John Summers 2021

First published 2021

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the permission of the publishers.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

p. 115: Four lines of the text of Lord of the Dance (Sydney Carter, 19152004), 1963 Stainer & Bell Ltd, 23 Gruneisen Road, London N3 1LS, www.stainer.co.uk, are used by permission. All rights reserved.

A catalogue record is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

ISBN 9781776564217 (print)

ISBN 9781776564590 (EPUB)

ISBN 9781776564606 (Kindle)

Published with the support of a grant from

Ebook conversion 2021 by meBooks

for Alisa and Henry

Contents

Within minutes you could erect shelter. Rubbing sticks together was as effective as a cigarette lighter. Such tasks were difficult enough to be interesting but never onerous. And the temperature was always right for swimming.

The Coral Island was a Victorian novel full of Victorian values I doubt it gets read much now and it tells the story of three English boys stranded on a Pacific island. I say stranded, but this was survival as holiday. Some of the happiest hours of my childhood were those spent sitting on the mat, listening to a teacher read from this book. I went about for weeks afterwards craving breadfruit, imagining something between a baked potato and bread fresh out of the oven, and I dreamed of islands, failing to twig that I was already on a Pacific island. In my mind it was somewhere else. These South Seas were too close, too familiar. I wasnt entirely wrong in assuming it was elsewhere. The author, a Scot named Ballantyne, had never been to the Pacific himself. His account was make-believe, a cobbling together of everything hed read. The Coral Island of the title was a veritable PaknSave, where the boys feasted on pigs, taro, yams, sweet potatoes, plums and sugar cane as well as cocoa nuts that could be stuffed a couple at a time in pockets and then opened easily with a knife, the juice lemonade-like. It was a fantasy, and it was very much a white mans fantasy. These were not islands where people lived and worked to make a living, but background, a stage set with all the messy business of school and work and life excised. When the locals did appear in The Coral Island they were just as phoney as the cocoa nuts, the usual cannibals and noble savages of Victorian literature.

And yet, although I know all this now, islands still have their appeal. There is surely a direct line from Defoe to Ballantyne to the House of Travel, and despite my better judgement that line runs within my brain too. The sight of hibiscus stirs something between hope and yearning, emotions similar to those I felt sitting on the mat, listening to my teacher read. And I have holidayed in Smoa, Tonga and Niue, coming to see, in the limited way that a tourist can, the realities of island life but also breadfruit in the wild, the opportunity to dispel that persistent myth, which is perhaps why Ive never eaten it, have allowed it to remain the perfect fruit of my daydreams.

This is all to say that when, on another island holiday, this time in Rarotonga, I came across a battered paperback about a New Zealander who had lived alone for years on an uninhabited Pacific atoll, I had no choice but to read it, to let it creep into any idle hours thought. I am far from alone in this. Tom Neales AnIsland to Oneself was published in 1966 in England, and would be translated into French, German, Dutch and even Persian. Its out of print now, but theres a readership still. Reviews crop up on Amazon and Goodreads, and copies float, flotsam in secondhand bookshops. Its a short book considering the time it covers, but Neale doesnt muck around. His prose is straightforward, as taut as he was photographs reveal the physique of a coat hanger. He allows himself only a brief exploration of the impulse to spend so much time alone on Suwarrow (then known as Suvarov), an atoll in the Cooks, attributing much of it to the influence of Robert Dean Frisbie, an American author who once spent a year there with his five children. The rest is Neales account of his voluntary marooning. Suwarrows last residents had been coast watchers, two bored men told to look out for a Japanese invasion that never came, and Neale moved into the tin shack theyd left behind. He grew a garden, raised chickens and caught fish to feed himself and the two cats hed brought. Easy to rattle off these tasks, but each was its own small feat. Establishing the garden meant hauling topsoil across the island and, once the plants grew, pollinating each by hand there are no bees on remote atolls. It was ten months before Neale saw another person, and all up he was there, alone, for two years, only leaving on a trade ship after suffering from back pain, which in Rarotonga was diagnosed as arthritis. Reason to give it up youd think, but he still craved his lonely island, and would have been back right away but for the Cook Islands authorities. They werent keen on the idea of Neale dying by himself in a remote corner of their territory, and refused him permission to return on any of the local vessels.

And so he went back to his original occupation: keeping shop. He ran a general store, selling kerosene, canned beef and dry goods. Six frustrating years is what hed call this time, describing 1950s Rarotonga as if it were an asphalt jungle. The cars at a nearby petrol station gave off stinking fumes. Life was governed by the clock, and he had to wear trousers on Suwarrow hed gone about in a hat and loincloth. Return would be a relief, and in 1960 he got around the authorities by travelling back to Suwarrow on a private yacht. He lived there for another two years, the time punctuated by the arrival of three castaways, a couple named Vessey and their young daughter Sileia, who were marooned when their yacht tore open against the islands coral reef. They lived with him for two months until all four were able to signal a passing New Zealand frigate. Neale left not long after their rescue, after more people arrived pearl divers from the nearest inhabited island, Manihiki and he learnt they would be returning regularly to dive in Suwarrows lagoon. Other voices, turning his heaven into hell.

Ballantynes The Coral Island would be updated by William Golding as Lord of theFlies bloodlust replacing all that breadfruit. And Tom Neales book has been updated too. While in Rarotonga, I learnt that his daughter, Stella Neale, wrote an epilogue to her fathers book that she hopes to publish one day. I got in touch, and she sent me a copy of her manuscript. Its a tender but clear-eyed document that tells another story a family story that runs alongside the original tale of the man alone on the island. Neale had a son at the time of his first stay on Suwarrow, and by the time he left for the second he was married with two more children: Stella and her brother Arthur. The six frustrating years that he described spending stuck in Rarotonga were in fact six years with his young family. He was a very private man, Stella wrote. To explain a private matter was not who he was, she offered as explanation for why none of this appears in her fathers book, and her description of him is of a loving if reserved father who rationed sweets and taught her his own skills of self-reliance. He had her opening coconuts with a sharpened crowbar and cutting wood with an axe when she was still in the single digits. He was also a stubborn man, certain about how things should be done. A useful quality on a desert island, where self-doubt has time to grow into despair.

Next page