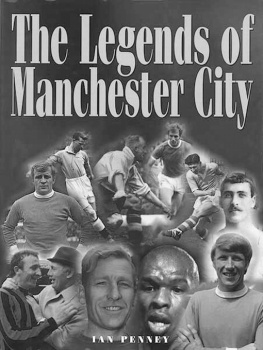

For Stuart and the fallen heroes of the team he loved with a quiet but steadfast passion...

Neil Young (19442011)

Mike Doyle (19462011)

George Heslop (19402006)

Harry Dowd (19382015)

A NOTE ON THE AUTHOR

James Lawton first started covering top-flight football as a 19-year-old for the Daily Telegraph in 1963 and, after a seven-year stint in North America, went on to become chief sports writer of the Daily Express and the Independent. He was three times voted sportswriter of the year and was also awarded the sports columnist and sports feature writer of the year titles. He has written 12 books, including an award-winning collaboration with Sir Bobby Charlton on his two volumes of autobiography.

Contents

One of the lesser distinctions of the Manchester City side which filled the late sixties with football of sometimes heartbreaking ambition was that, as it turned out, they were the team of my youth. They were the bearers of light, the recreators of long-dormant hope, the boys who said to anyone who was listening that if you wanted something badly enough, well, there might just be ways and means of getting it.

The best part of 50 years may strike you as a long time to gain a proper understanding of the meaning of a single football team but then, dont we know the older we get, there are a few distractions along the way.

Maybe you will also find it strange that the impetus to return to a side that was filled with the most thrilling optimism and spirit, and some gloriously swift accomplishment, should be born in, of all places, a cemetery.

Odd, perhaps, because so often we go to a funeral not so much to recognise the passing of anothers life, however dear or engaging or influential it was to brush against, or even inhabit to some degree, but the loss of a certain purpose and optimism in our own. We sit in a church stall and we think of how it once was and how it can never be so again. We consider the erosion of the years and the seepage of hope, in our own existence and that of the one we are there to acknowledge.

Yet it isnt always so, and certainly it wasnt when we came out of the bright autumn sunshine and into the crematorium chapel to pay our last respects to Malcolm Allison.

Maybe we had gone there to regret the pain and the sad detachment and confusions of his last years, but we felt another force, sudden and contagious, and afterwards when we stood in the churchyard we spoke of it freely, even exultantly. We were no longer mourners but celebrants. And what was it we celebrated? It was a time in our lives when anything seemed possible, when everything was before us, and when a group of young footballers, ageing now but extremely proud, so brilliantly embraced the idea that if they worked hard enough, if they explored all of their resources, there might not be anything theyd fail to achieve.

There was, of course there always is a degree of failure and the reality of this weighed most heavily on the man to whom we said farewell that October afternoon in 2010. But there was solace for those who cared most about him, so often in spite of the worst of his destructive nature, and it was expressed in this surge of the spirit, this quickening of the stride.

It was as though he was, as the imprisonment of dementia slid away, restored to all of his old outrageous glory.

We could look around and see how many people he had touched, for good and bad, for great and no doubt frequently reckless pleasure and also pain. Francis Lee, the superbly pugnacious player so important to the achievements of Manchester City between 1967 and 1970 that would always represent the peak of Allisons work, put it most succinctly. He cocked his ear at the sound of a police car siren blaring along the nearby Princess Parkway and as he thought of all the scrapes and dramas of the man he had once described, not without a degree of affection and admiration, as an arrogant bastard, he said with his most puckish grin, Theyre too late. Malcolms got away one last time.

From their first meeting, Lee had been a particular delight of Allisons as he shaped his startling team in those brief, good years when he still listened to his mentor, Joe Mercer. Allison loved Lees hauteur, his edge, his ability to inflict himself on any situation and, maybe most of all, the sense that he would never renege on the commitments he had made to himself. One of Allisons warmest memories was of Lees protest at slow service in a San Francisco restaurant. In mock exasperation, Lee had plucked flowers from a bowl on the table and began to chew them.

Allison, with some reason, believed that he had created extraordinary potential and appetites in his team, and having done so was entitled to speak of his players in superlatives.

So Lee was filled with the authority of a gunfighter. Colin Bell was Nijinsky, named for the great thoroughbred not the mad dancer. Mike Summerbee was a man of fierce talent and unbreakable pride. Tony Book was the quick and knowing veteran, rescued, almost entirely by him, from a mediocrity which would have been the most unjust of fates.

They mingled now, the old elite of Manchester City in the last of the sunlight, and they formed an animated consensus with former colleagues like Joe Corrigan, the young, towering goalkeeper who had, with Allisons help, defied all doubts about his native talent, and the Cheshire cousins Glyn Pardoe and Alan Oakes, who were so quickly persuaded by their new coach that they were great players. Everything they said was a vindication of a man they believed had been too easily discounted, too readily scorned.

Allison had his faults, and not too few to mention, but still they had to be measured against quite what he had first given, and when you thought of that, when you considered the extent of the gift, so many of his misadventures, and the ensuing red ink which had so smeared the details of his later life, were surely reduced sharply in this last accountancy, if not washed away.

Allisons striking eldest daughter, Dawn, had stood up in the chapel and put aside all of the disruptions and discomfort and hurts that had accompanied her fierce love for a father who was so often absent. She said that if she had learned anything from him it was that you should never waste a second of your life. That was his dogma when his career was most exciting and productive, and here were so many witnesses to say that his ability to transmit the value of that belief had never left them, even in the most unpromising of circumstances.

But then this, if you were wondering, is not the story of Malcolm Allison, the details of which have been recounted and, perhaps, retouched often enough, but it is one which would never have begun to unfold had he not parked his beaten-up Borgward which had a Shell sticker on the windscreen in place of a current road tax label in front of Citys old Maine Road stadium on an early summer morning of 1965. It is an account of a brief passage of time seen through the eyes of a football team which made itself permanent in the hearts of all those who played in it and so many who saw it. Certainly for a young reporter of those thrilling years it seemed that the strength of what happened, the extraordinary force of it, might now be assessed afresh, not just for its impact on those half-forgotten days but for the durability of a legacy that was still so alive and evocative in all the lives that it had touched.

At least that was my instinct as I drove away from Southern Cemetery, Manchester, with such an overwhelming sense that something from deep in the past had been awakened. I may have gone there to consign, with sadness and maybe a tinge of old guilt, those players and their creator to some obscure page of sporting history, some recess of an unformed, abandoned memory, but now there was the feeling that maybe this just wouldnt do. Perhaps there was something more to be said about what happened all those years ago and its unshakeable consequences for all those who took part? Maybe there were questions to ask again, a time, a mood, a state of mind to reassess along those iron chains of recollection that ultimately hold against all neglect?