Sex, Drugs, and

Rock 'n' Roll

Sex, Drugs, and

Rock 'n' Roll

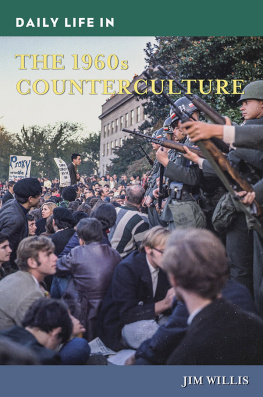

The Rise of America's 1960s

Counterculture

Robert C. Cottrell

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2015 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

Cottrell, Robert C.

Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll: The rise of America's 1960s counterculture / by Robert C. Cottrell.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-4606-5 (cloth : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-4422-4607-2 (electronic)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To Harry, Edie, Ruthie, Steve, Sharon, Bill, and Sue,

children of the 1960s

and to Jordan, a child of children of the 1960s

Preface

They believed, like good sons and daughters of a new American frontier, in the possibility of rebirth, of renewal, of regeneration. They saw themselves as born anew, ironically, in the manner of religious fundamentalists, as spirits whose souls had been cleansed once more. Some considered their quest to be very much in the American vein; others likened it to a sacred journey to the East. Many sought to rekindle a democratic and communitarian tradition that had apparently long since dissipated. Their example, they keenly reasoned, would help to revitalize not only their fellow citizens but humankind in general.

There was certain innocence in their quest, and yes, a very real naivet and arrogance as well. They presumed that they could transform society and achieve spiritual bliss in a manner only the sanctified few had ever accomplished. They deemed their way as wholly righteous, drawing as it did on religious preachments of both the occidental and oriental variety. They were sure that their path toward illumination was eased or ensured altogether by lifestyle changes they effected, by their discarding of the competitive and rational ways that had brought so much misery to so many, and by the ingesting of pharmacological substances that seemingly promised instant enlightenment.

They were the hippies of the 1960s, the proponents of a counterculture, which stood in opposition to established ways, values, and verities, and to the so-called Establishment itself. Indeed, they saw themselves and were viewed by others as a group apart, as either the progenitors of a new and better means of making ones way in the world or a faddish, ungrateful, and aberrational force in the midst of American plenty. Again, each side had it right, at least from the perspective of its celebrants. For the hippies proved to be a short-lived phenomenon, perhaps because they were considered ingrates and freaks in the eyes of others, with their rejection of the American way. Yet for a time, the best, the most idealistic of them strove to attain something both more elemental and purer, no matter how frivolous and lighthearted they appeared to others.

Perhaps the intensity of the reaction to the hippies, both laudatory and accusatory, indicates as much. They were likened by some to a band of new Christs and Madonnas, and by others as the latest brand of American Adams and Eves, out to chart a new course in the wilderness of human existence. They were viewed as such by millions of the young in age and in spirit, who desperately sought new answers or a guiding light as an apparent age of darkness threatened to apocalyptically envelope the national landscape. They were damned by others as diabolical creatures, more Satanic than God-like, or at the very least as wholly irresponsible sorts, who were determined to waste their own lives, while leading youthful cohorts astray and perverting America. They were seen as little likely to usher in a new millennium, but rather as bound to bring about the collapse of the social order, which was already more tenuous than it had been for decades or longer, and hardly required anything akin to a misguided childrens crusade.

The hippies, like the antebellum communitarians, Greenwich Village bohemians of the preWorld War I period, and the beats who haunted Eisenhowers America, were an integral part of their age. The utopians were part of the spate of reform movements that flourished in the United States before the Civil War. The bohemians characteristically exuded the innocence and exuberance of the Lyrical Left of John Reed, Mabel Dodge, Floyd Dell, and Bill Haywood, which developed during the progressive era. The beats stood in stark contrast to the complacency, conservatism, and conformity of the 1950s, a security-riddled period seemingly haunted by ever-present communists, both authentic and phantasmagoric. The hippies appeared during the same period that the New Left supposedly threatened the ideological hegemony of the liberal center, which shone briefly thanks to the appeal of the New Frontier and the Great Society.

Thus, all but one of the countercultures of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including that of the 1960s, evolved when the reform spirit was ascendant and an American left present. Indeed, the hopefulness and expectations raised by presidents John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Lyndon Baines Johnson, as much as disillusionment spawned by fading dreams and visions of the early part of the decade, set the stage for the arrival of the cultural rebels of the mid- and late sixties. Still, those rebels were undoubtedly influenced by images from Birmingham and Dallas, Watts and Saigon, Memphis and Los Angeles, which filled the pages of local newspapers and the small screens of television sets. Likewise, they took to heart tales of the new Greenwich and Liverpool, Golden Gate Park and Monterey, Paris and Chicago. The hippies truly were children of a media-driven age, with its panoply of adrenalin-like fixes and its haunting images from the McLuhanesque global village.

Their icons were multifold, and, notwithstanding suggestions to the contrary, not all were of the simplistic or nonliterate variety. Some, at least, read widely, including Buddhist masters, European Nobel laureates, Middle Eastern poets, British folklorists, American science-fiction writers, popular novelists, beats, and sexologists, in addition to Timothy Learys instructional manual The Psychedelic Experience or Ken Keseys One Flew over the Cuckoos Nest. Many idealized rock musicians, with none more revered than four young Englishmen and a tousle-haired former folk musician from Americas heartland. A good number venerated the ways, the style, the social patterns, and the grace of those often depicted as outsiders, particularly Native Americans and outlaws of one kind or another. Indeed, many of their heroes boasted antiheroic stripes.

The hippies attempted to shape an idealized existence, through their own music and poetry, their communes and collectives, their underground press and other alternative institutions, their clothing and dietary habits, their drug and sexual experimentation, and their religiosity and spirituality. Some of their endeavors were more successful than others, and some longer-lived. All, for better or worse, influenced how Americans came to interact with one another in their most intimate relationships, in educational and recreational spheres, and even in the corporate world. Similarly, hippie modes and manners affected apparel and hair styles, foods consumed or refused, as well as language and general patterns of thought.

Next page

![Robert Greenfield - Timothy Leary: A Biography [excerpts]](/uploads/posts/book/113331/thumbs/robert-greenfield-timothy-leary-a-biography.jpg)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.