Two Pioneers

Other Titles from Potomac Books

The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the

Negro Leagues, by Bob Luke

Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story, by Curt Smith

Jewish Sports Legends: The International Jewish Sports Hall of

Fame, fourth edition, by Joseph M. Siegman

Two Pioneers

HOW HANK GREENBERG AND JACKIE ROBINSON TRANSFORMED BASEBALLAND AMERICA

ROBERT C. COTTRELL

Copyright 2012 Potomac Books, Inc.

Published in the United States by Potomac Books, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cottrell, Robert C., 1950

Two pioneers : how Hank Greenberg and Jackie Robinson transformed baseballand America / Robert C. Cottrell.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59797-842-2 (hardcover: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-59797-843-9 (electronic edition)

1. Baseball playersUnited StatesBiography. 2. Greenberg, Hank. 3. Jewish baseball playersUnited StatesBiography. 4. Robinson, Jackie, 19191972. 5. African American baseball playersBiography. I. Title.

GV865.A1C67 2012

796.3570922dc23

[B]

2012000672

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standards Institute Z39-48 Standard.

Potomac Books

22841 Quicksilver Drive

Dulles, Virginia 20166

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Sue and Jordan,

and in memory of Sylvia Light Cottrell,

a lifelong St. Louis Cardinals fan

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Once again, I owe a debt of gratitude to my literary agent Robbie Hare of Goldfarb & Associates. She provided entre to Potomac Books, where I have had the pleasure of working with senior editor Elizabeth Demers and production editor Aryana Hendrawan.

This book acquired its gestation many years ago, receiving impetus from an extended stay in Cooperstown, New York, where I conducted research at the Baseball Hall of Fame Library. Helping me rifle through files and examine photographs were my wife, Sue, and my then nine-year-old daughter, Jordan, who photocopied a large number of materials on both Hank Greenberg and Jackie Robinson. Tim Wiles, director of research at the Baseball Hall of Fame, proved friendly, helpful, and supportive. I returned to Cooperstown on other occasions, and also carried out research at the Sporting News Archives in St. Louis, where Steven P. Gietschier, director of historical records, also assisted in my research endeavors. Visits to the Library of Congress provided additional useful information, enabling me to acquire primary documents on Robinsons military service and to pore over a large number of microfilm reels, particularly those associated with newspapers in Brooklyn, New York City, and Detroit; black-run newspapers; and sports publications such as Baseball Magazine, Sporting Life, and The Sporting News. More recently, John Horne of the Photo Archives at the National Baseball Hall of Fame has been very kind in fielding queries, providing information, and delivering pristine images of my two subjects.

As always, Sue and Jordan were supportive throughout the entire writing process, serving as sounding boards and fans of two of baseballsand Americasmost important sports figures.

INTRODUCTION

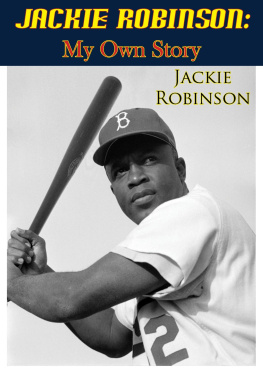

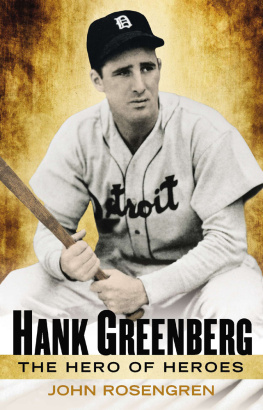

Hank Greenberg and Jackie Robinson are forever linked because of the barriers they encountered, the discrimination they endured, and the athletic gifts they exhibited. Greenberg was the first great Jewish major leaguer and Robinson the first African American player in organized baseball during the twentieth century. Both suffered ridicule and abuse. Each nevertheless excelled. Greenberg became one of the preeminent sluggers of the 1930s and 1940s. Robinson, from the mid-1940s into the following decade, helped bring back speed and a thinking mans approach to the game, both of which had largely been discarded for a generation.

Greenbergs numbers, compiled in a sport where statistics are more important than in any other, are arguably more impressive. He garnered four home-run and runs-batted-in (RBI) titles, came within two round-trippers of tying Babe Ruths single season mark, and fell one RBI short of Lou Gehrigs American League record. Greenbergs lifetime home run total when he retired after the 1947 season was the fifth greatest in major league history, and he had been awarded a pair of most valuable player awards. Even Greenbergs career batting average, .313, was two points higher than Robinsons. Robinsons record was impressive in its own right. It included one year when he got over 200 hits, six seasons when he scored more than 100 runs, six campaigns when he batted over .300, a batting championship, two stolen base titles, and an MVP crown of his own. Robinson helped lead his Brooklyn Dodgers to six National League pennants and their only World Series championship when the Boys of Summer finally defeated the New York Yankees in the 1955 Fall Classic. Greenbergs Detroit Tigers won four pennants and a pair of World Series, in 1935 and 1945.

Both men, along with their teams, undoubtedly would have accomplished even more on the baseball diamond but for fate and the circumstances they faced. Because of injuries and extended military service, Greenberg effectively played major league ball for only nine-and-a-half years. His 1936 season was all but aborted due to a broken wrist, while World War II pulled him away from the ballpark for four-and-a-half years when he was at the pinnacle of his game. Robinson, another military veteran and one who suffered a court-martial because of his refusal to accept Jim Crow practices, did not sign a contract with the Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey until he was twenty-six years old. He entered the majors almost two years later. The color barrier had kept out Robinson, as it had so many other stellar African American ballplayers. At the same time its presence in other sports, including professional football and professional basketball, ironically enough compelled Robinson to become a racial pathfinder in organized baseball. Had pro football not contained racial strictures of its own, Robinson, a star tailback at UCLA, undoubtedly would have been drafted by a National Football League team. If the American Basketball League and the National Basketball League, predecessors to the Basketball Association of America (which itself evolved into the National Basketball Association in 1949, following a merger with the National Basketball League), had not closed their doors to black players, Robinson, a two-time college conference scoring champion, could have played professional basketball. With a foot in the NFL or a professional basketball league, he likely never would have entered major league baseballbaseball was hardly his favorite sportor even played with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro National League, as he did for a season before signing with Brooklyn.

The two mens paths literally crossed during the epochal 1947 seasonRobinsons first and Greenbergs last in the major leagueswhen they collided

Nine years after that collision at first base, Greenberg was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Robinson joined him six years later. But the athletic prowess of the two men, as considerable at it was, was overshadowed by what they experienced and represented. Throughout much of the period in which Greenberg starred in the American League, anti-Semitism flourished as never before, even considering its lengthy history. Greenberg joined the Tigers lineup as the 1933 season began, just months after Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany. Five years later Greenberg ended the 1938 season, having failed to homer in any of the Tigers last five games in a futile attempt to match Ruths single season home run record. On November 9, 1938, the Nazis conducted

Next page