Chapter One

PLAYING FOR THE CHAMPIONSHIP

With almost 64,000 fans filling Yankee Stadium, Jackie Robinson was ready to play. His Brooklyn Dodgers had reached the World Series four times during Robinsons career. Each time they had faced the powerful New York Yankees. Each time Robinson and his teammates had ended their season watching the Yankees celebrate another World Series title, making them the champions of Major League Baseball. Would the 1955 World Series be different?

To the Dodgers and their fans, the Yankees were not just another team. Although the two teams played in different leagues and different parts of New York City, they were still rivals. The World Series gave fans of both the Yankees and the Dodgers a chance to see their favorite teams face off, with the winners getting to brag they were the best team in the city, not to mention the major leagues.

But for the Brooklyn team, the bragging had been missing. They had never won a World Series and had only played in three before Robinson joined the team. The Yankees, meanwhile, had won 16 World Series before 1955, including five in a row from 1949 to 1953. Dodger fans affectionately called their team Dem Bums, but it was frustrating to watch the Dodgers lose season after season. All the fans could say was Wait til next year.

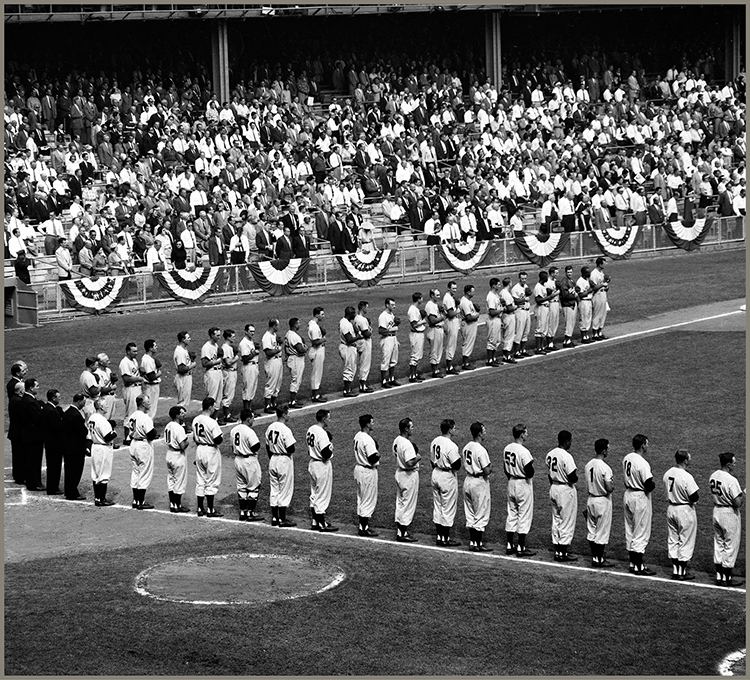

The stars of the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers were ready to take the field: Carl Furillo (from left), Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, Preacher Roe, and Gil Hodges.

A decade before the 1955 World Series, Robinsons baseball skills and personality attracted the attention of was a fact of life. African-Americans werent allowed as guests in hotels and restaurants meant for white customers. Most blacks in the South could not vote, and their children went to inferior schools.

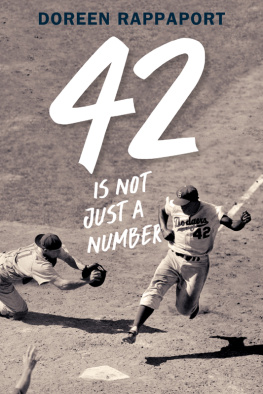

Before Jackie Robinson (left) moved up to the major league Dodgers, Branch Rickey signed him to a contract on October 23, 1945, to play with the Montreal Royals, the Dodgers top minor league team.

When he spoke his mind about racial issues or the treatment he received, some whites thought he was complaining too much. Stepping to the plate or taking his position on the field, Robinson often heard boos. A sportswriter told him that the press and some fans disliked him because he was too aggressive. Few white players would have been criticized for that, or for speaking honestly about their treatment, as Robinson often did.

Robinson officially broke the color line April 15, 1947, when he made his major league debut against the Boston Braves at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn.

Robinson played a huge role in getting the Above anything else, he once said, I hate to lose.

In 1947 Robinson became the first major league player to receive the Rookie of the Year award.

Before the 1955 season began, however, he didnt know how long he could keep playing. Although still a fast runner, he had slowed down a bit. And injuries sometimes limited his playing time. He began thinking about life beyond baseball.

Robinson missed nearly one-third of the 1955 season because of injuries and age. But as the .

The Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Yankees lined up before the start of a 1955 World Series game at Yankee Stadium.

Despite his contributions, some baseball experts wondered whether Robinson would be a starting player in Game 1 of the World Series against the third base.

The Dodgers scored first, getting two runs in the top of the second inning. Robinson contributed with a triple and then scored on a single by Don Zimmer. The Yankees tied the score in the bottom of the inning. In the third, Brooklyn scored again, only to see the Yankees once again tie it. Over the next three innings, the Yankees took a three-run lead. The score was still 6-3 in the eighth when Robinson came to the plate with one out and a man on first. He once again faced the Yankees Whitey Ford, one of the top pitchers in the game. Robinson hit a ground ball that third baseman Gil McDougald could not field cleanly. Robinson reached second on the error, then went to third on a sacrifice fly. The sacrifice had scored the runner ahead of him, so now, with the score 6-4 and two outs, Robinson looked at home plate just 90 feet (27 meters) away.

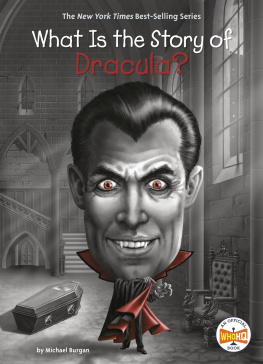

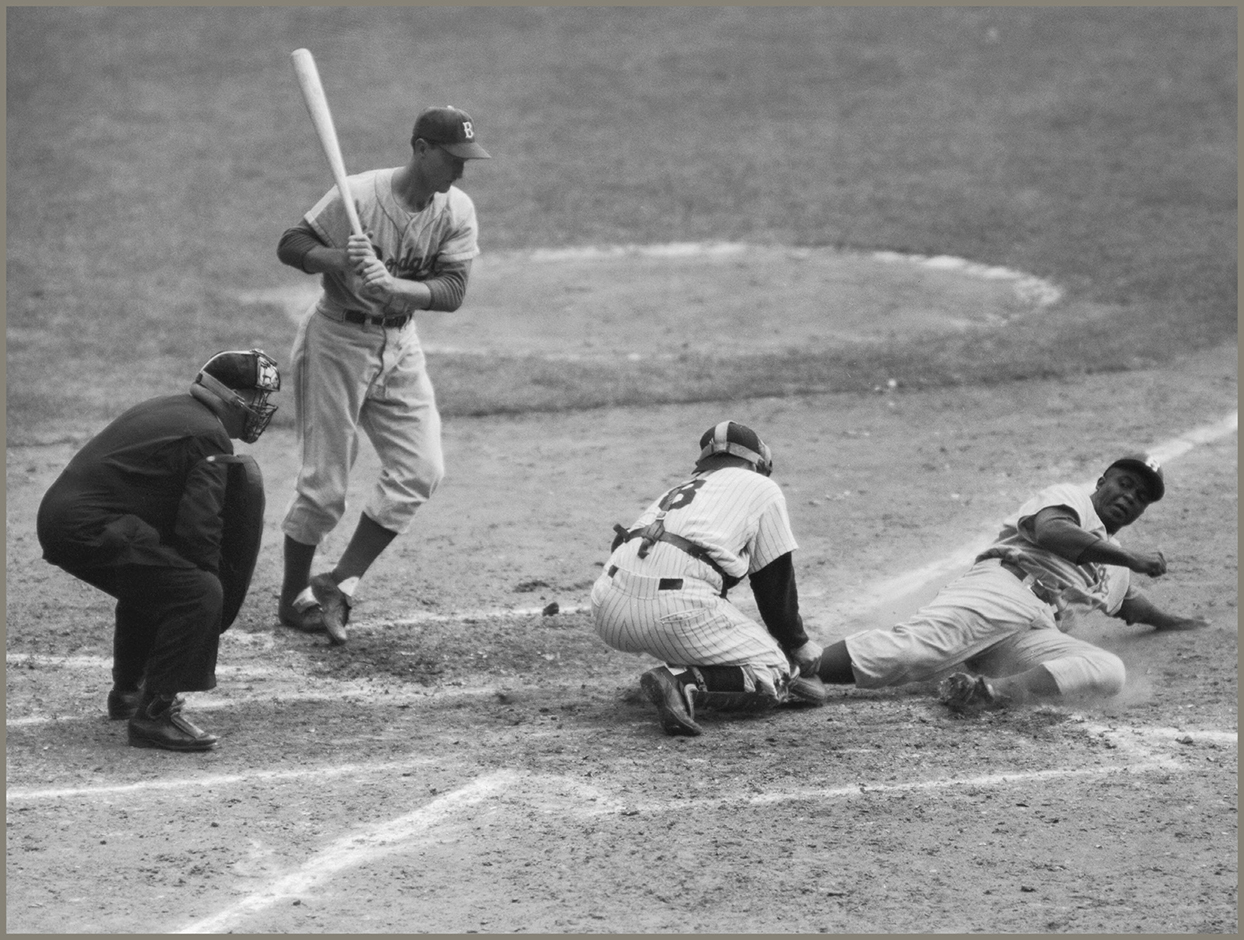

Robinson later wrote that he stood on third base thinking this could be his last year in baseball, his last chance to help Brooklyn win a World Series and defeat their New York rivals. It was not the best baseball strategy to steal home with our team two runs behind, but I just took off and did it.

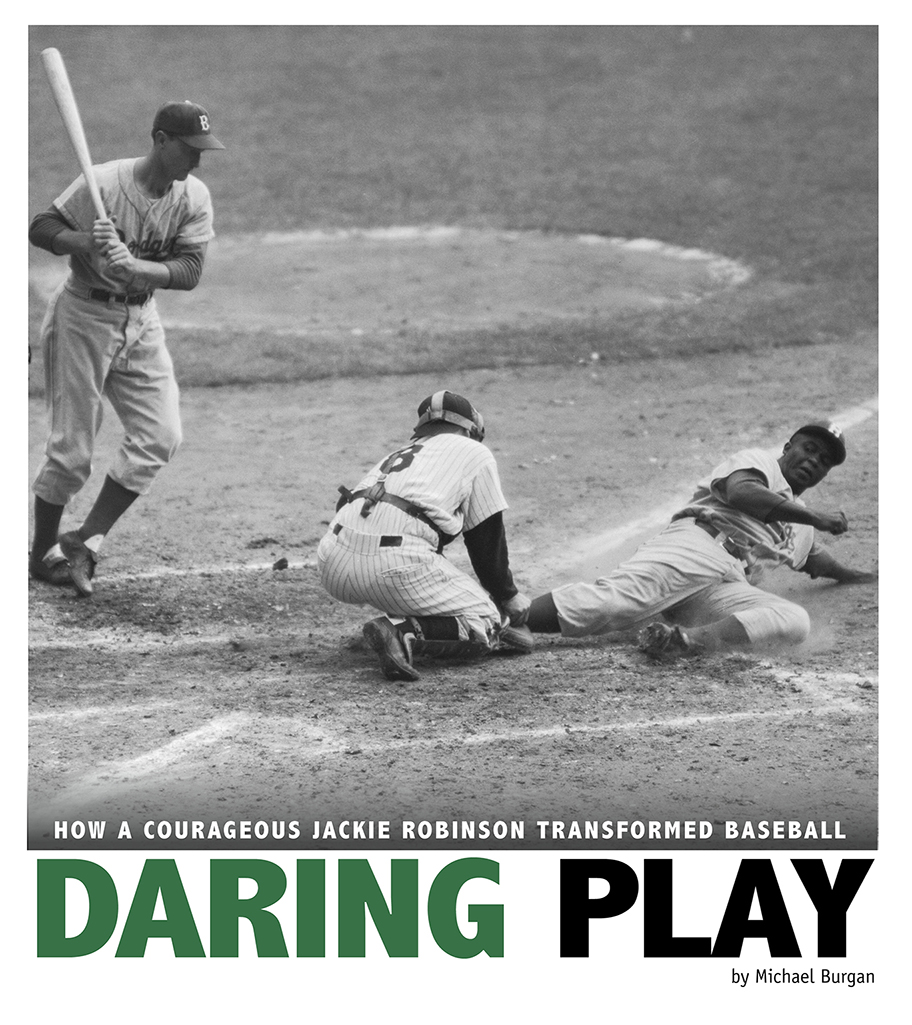

Robinson slides under the mitt of Yankee catcher Yogi Berra to steal home in the 1955 World Series in one of baseballs most famous photographs.

What happened when Jackie Robinson stole home in the World Series led to a controversial call at the plate. It also led to one of the most famous photographs from Robinsons historic career.

THE SLOW PACE OF INTEGRATION

Major League Baseball and sports historians note that while Jackie Robinson made history, he was not the first black to play professional baseball on a team with whites. Robinson made history by breaking the color line that had been in force since the late 1800s. The color line meant that only whites were allowed to play for the major league teams and for the minor league teams that helped train their players.

During the 1870s Bud Fowler became the first African-American known to play professionally for a white club. Like Robinson, Fowler was a skilled infielder. The first black player known to play regularly in a major league was Moses Fleetwood Walker, a catcher. He played for Toledo, which joined one of the first major leagues, the American Association, in 1884. Soon after, however, the color line returned to baseball. Historians place much of the blame on Adrian Cap Anson, the manager and star player of the National League team in Chicago now called the Cubs. Anson had strong racist views and refused to allow his team to play against Walkers team or any other team with an African-American player. By the end of the century, no blacks played in the major leagues or for the top minor league teams.

Robinsons success with the Brooklyn Dodgers answered any questions about whether African-Americans deserved to be in the major leagues. Honest baseball players and fans had known the answer for some time. White stars often played against stars of the Negro Leagues, teams made up of African-American players. White players and fans saw that the talents of the top black players matched or exceeded those of many white major leaguers. Even so, most major league clubs were slow to sign black players. By 1952 only five other teams had joined the Dodgers in integrating their rostersthe Cleveland Indians, St. Louis Browns, New York Giants, Boston Braves, and Chicago White Sox.