Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my mother and her motherand to my grandfather, who loved them both

Im fascinated by World War II, having been a participant. I read everything I can and everything thats ever written about it. I must read it, you know?

HANK GREENBERG , 1980

A Note to the Reader

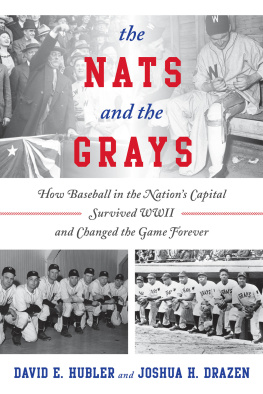

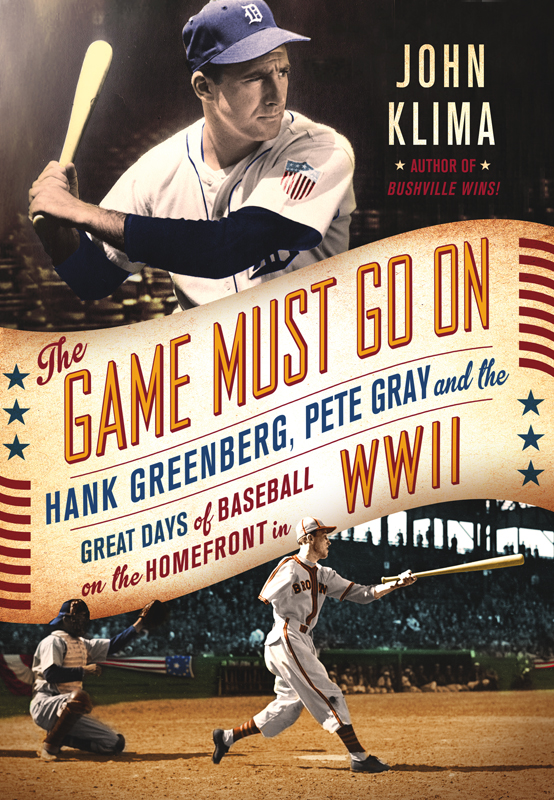

The story of the war and baseball is the story of us. If you care about baseball, everything you know about baseball comes from what happened during World War II. If you care about World War II, this is a new version of the war story you have never read. The war created who we are and it created modern baseball, and from that came the evolution of modern professional sports today, because the games we play changed because of the battles we fought.

I set out to write this story because I thought that the people who write about baseball dont know much about World War II, and the people who write about World War II dont know much baseball. I grew up with both in my life and always felt that the grand story of baseball and the war had never been told in a cohesive, narrative style that explained why the two are connected, and how we can see it, even if we dont realize it, in our lives today.

When I would find the few books written about baseball during the war, I couldnt stand the lack of knowledge about the wars basic campaigns, personalities, or machines. As for the war writers, theyre interested in the war, so they never stopped to ask what baseball meant to the soldiers and to the home front or who was involved. But this connection between baseball and the war was part of our national identity and remains a pivotal part of our history.

Back in the war, pilots had maps printed on their silk scarves in case they were shot down. So in this note, Id like to provide the reader with a short road map of what to expect, a comfortable fit, one that welcomes you into the world of your parents and grandparents, so that you can visit them again, whether they are here with you or not.

The basics: Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941, in the baseball off-season. Nobody knew if baseball would be permitted to continue because the war was going to require millions of men. We needed them for the Army, the Air Force, the Navy, and the Marine Corps. Somebody had to build all the equipment. That meant millions more men and women working in factories at home and a tremendous strain on the resources that made possible baseball and everything else routine in American life.

The baseball commissioner was Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis. He asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt what baseball should do. Landis wanted to know if baseball was important enough to continue during the war. This was a complicated decision. After much pondering, FDR wrote a note called the Green Light Letter, saying, in effect, the Game Must Go On.

The reader should be introduced to three principal characters before we begin this story. They may or may not be known to you. One man is Hank Greenberg. He was a big-time home-run hitter for the Detroit Tigers. He was the first major league baseball star to enter the Army, and soon, every other significant star followed him into the war effort. One by one they left the majors: players such as Bob Feller, Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, and Stan Musial. So did lesser-known ballplayers, who are well worth meeting: Buddy Lewis, Phil Marchildon, Jake Jones, Bert Shepard, Hank Bauer, Bill Greason, Warren Spahn (he was a nobody when the war began), and others introduced throughout this story.

Another player you should all meet is Pete Gray, who lost his arm at age six when he was essentially run over by a truck. He played baseball his whole life, longing for a chance to play professionally, but because he was an amputee, he was rejected and often ridiculed. The wars manpower shortage created his opportunity, and he got to play in the big leagues for one year because the Army would not take him because of his disability. He became the symbol of the imperfect players who kept the majors going on the home front. He was also an inspiration to wounded servicemen everywhere. Petes story resonates especially now, as a generation of amputees have come home from Iraq and Afghanistan to become wounded-warrior athletes who prove the power of determination.

The final player is a boy named Billy Southworth, who, for the young parents reading this, could have been just like your son. He was a promising ballplayer headed to the big leagues. He had it made because his father was the manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, the best team of the war years. But Billy wanted to fly and wanted to serve, and he got his wish, quitting baseball, then flying and fighting aboard a B-17 bomber in the skies of Europe.

I wonder if the culture of vanity and narcissism we have created in this country today would permit such wide-scale selfless sacrifice at the cost of money, fame, and career. In the war years, thousands of athletes from all sports, amateur and professional, from all nations, decided that winning the war, a collective goal, was more meaningful than individual accomplishment. Playing a professional sport, while requiring great commitment, effort, and dedication, is not the same as fighting a war. The level of sacrifice and commitment from the World War II generation was far more substantial than wearing a flag pin on the lapel or singing the national anthem as if it were a tryout for a TV talent show.

Professional athletes have become an untouchable class in modern American society. In the war years, they were also celebrated, but they were not permitted to put career above country. The president of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, said so. The result was the baseball manpower shortage of World War II, the greatest crisis the game has ever faced, the price to be paid for keeping baseball going as a morale booster for the war effort at home and at the front. It is also why modern professional baseball looks the way it does, and because the other American sports, namely football and basketball, have copied baseballs evolution, which adapted to the manpower shortage, so, too, can it be said that the modern sporting landscape we have as Americans can be traced to what happened to baseball during the war. The manpower crisis changed the entire way modern athletes are bought and sold, placing a focus on youth. Now, the zest to discover and celebrate adolescent athletes borders on disturbing.

Most of what Americans know about baseball, or their other favorite sports, comes from what happened to baseball in World War II. The amateur draft, the integration of African-American and Latin players, unionization, free agency, big media deals, franchises changing cities, construction of new stadiums, rapid economic expansion and growth, all came from baseball and the war. The war made the country come of age and took the games we play with it. This is that story, too.

The war is the dividing line between baseball as it developed in America from the 1860s until the 1940s, and baseball and modern American sport as it has developed from 1941 to 1945 and into the twenty-first century. The saga of baseball and World War II is the earths crust of baseball history. Nothing matches its wide-scale influencenot gambling scandals, not drug and steroid scandals, not labor stoppages or skyrocketing salaries, not any one era, not the achievements of any individual player, team, game, or series. Baseball in the war belongs with the ages.