The author wishes to apologize for the constant use of the word English in speaking of the British Expedition to France. At the beginning of the war this was a colloquial error into which we all fell over here, even the French press. Everything in khaki was spoken of as English, even though we knew perfectly well that Scotch, Irish, and Welsh were equally well represented in the ranks, and the colors they followed were almost universally spoken of as the English flag. These letters were written in the days before the attention of the French press was called to this error of speech, which accounts for the mistakes persisting in the book.

June 3, 1914

Well, the deed is done. I have not wanted to talk with you much about it until I was here. I know all your objections. You remember that you did not spare me when, a year ago, I told you that this was my plan. I realize that you more active, younger, more interested in life, less burdened with your past feel that it is cowardly on my part to seek a quiet refuge and settle myself into it, to turn my face peacefully to the exit, feeling that the end is the most interesting event ahead of me the one truly interesting experience left to me in this incarnation.

I am not proposing to ask you to see it from my point of view. You cannot, no matter how willing you are to try. No two people ever see life from the same angle. There is a law which decrees that two objects may not occupy the same place at the same time result: two people cannot see things from the same point of view, and the slightest difference in angle changes the thing seen.

I did not decide to come away into a little corner in the country, in this land in which I was not born, without looking at the move from all angles. Be sure that I know what I am doing, and I have found the place where I can do it. Some time you will see the new home, I hope, and then you will understand. I have lived more than sixty years. I have lived a fairly active life, and it has been, with all its hardships and they have been many interesting. But I have had enough of the city even of Paris, the most beautiful city in the world. Nothing can take any of that away from me. It is treasured up in my memory. I am even prepared to own that there was a sort of arrogance in my persistence in choosing for so many years the most seductive city in the world, and saying, Let others live where they will here I propose to stay. I lived there until I seemed to take it for my own to know it on the surface and under it, and over it, and around it; until I had a sort of morbid jealousy when I found any one who knew it half as well as I did, or presumed to love it half as much, and dared to say so. You will please note that I have not gone far from it.

But I have come to feel the need of calm and quiet perfect peace. I know again that there is a sort of arrogance in expecting it, but I am going to make a bold bid for it. I will agree, if you like, that it is cowardly to say that my work is done. I will even agree that we both know plenty of women who have cheerfully gone on struggling to a far greater age, and I do think it downright pretty of you to find me younger than my years. Yet you must forgive me if I say that none of us know one another, and, likewise, that appearances are often deceptive.

What you are pleased to call my pride has helped me a little. No one can decide for another the proper moment for striking ones colors.

I am sure that you or for that matter any other American never heard of Huiry. Yet it is a little hamlet less than thirty miles from Paris. It is in that district between Paris and Meaux little known to the ordinary traveler. It only consists of less than a dozen rude farmhouses, less than five miles, as a bird flies, from Meaux, which, with a fair cathedral, and a beautiful chestnut-shaded promenade on the banks of the Marne, spanned just there bylines of old mills whose water-wheels churn the river into foaming eddies, has never been popular with excursionists. There are people who go there to see where Bossuet wrote his funeral orations, in a little summer-house standing among pines and cedars on the wall of the garden of the Archbishops palace, now, since the separation, the property of the State, and soon to be a town museum. It is not a very attractive town. It has not even an out-of-doors restaurant to tempt the passing automobilist.

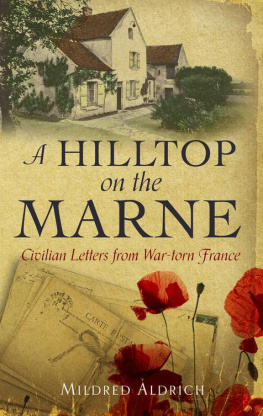

My house was, when I leased it, little more than a peasants hut. It is considerably over 150 years old, with stables and outbuildings attached whimsically, and boasts six gables. Is it not a pity, for early associations sake, that it has not one more?

I have, as Traddles used to say, Oceans of room, Copperfield, and no joking. I have on the ground floor of the main building a fair-sized salon, into which the front door opens directly. Over that I have a long, narrow bedroom and dressing room, and above that, in the eaves, a sort of attic workshop. In an attached, one-story addition with a gable, at the west of the salon, I have a library lighted from both east and west. Behind the salon on the west side I have a double room which serves as dining and breakfast room, with a guest chamber above. The kitchen, at the north side of the salon, has its own gable, and there is an old stable extending forward at the north side, and an old grange extending west from the dining room. It is a jumble of roofs and chimneys, and looks very much like the houses I used to combine from my Noahs Ark box in the days of my babyhood.

All the rooms on the ground floor are paved in red tiles, and the staircase is built right in the salon. The ceilings are raftered. The cross-beam in the salon fills my soul with joy it is over a foot wide and a foot and a half thick. The walls and the rafters are painted green, my color and so good, by long trial, for my eyes and my nerves, and my disposition.

But much as I like all this, it was not this that attracted me here. That was the situation. The house stands in a small garden, separated from the road by an old gnarled hedge of hazel. It is almost on the crest of the hill on the south bank of the Marne the hill that is the watershed between the Marne and the Grand Morin. Just here the Marne makes a wonderful loop, and is only fifteen minutes walk away from my gate, down the hill to the north.

From the lawn, on the north side of the house, I command a panorama which I have rarely seen equaled. To me it is more beautiful than that we have so often looked at together from the terrace at Saint-Germain. In the west the new part of Esbly climbs the hill, and from there to a hill at the northeast I have a wide view of the valley of the Marne, backed by a low line of hills which is the watershed between the Marne and the Aisne. Low down in the valley, at the northwest, lies Isles-ls-Villenoy, like a toy town, where the big bridge spans the Marne to carry the railroad into Meaux. On the horizon line to the west the tall chimneys of Claye send lines of smoke into the air. In the foreground to the north, at the foot of the hill, are the roofs of two little hamlets Joncheroy and Voisins and beyond them the trees that border the canal.

On the other side of the Marne the undulating hill, with its wide stretch of fields, is dotted with little villages that peep out of the trees or are silhouetted against the skyline Vignely, Trilbardou, Penchard, Monthyon, Neufmortier, Chauconin, and in the foreground to the north, in the valley, just halfway between me and Meaux, lies Mareuil-on-the-Marne, with its red roofs, gray walls, and church spire. With a glass I can find where Chambry and Barcy are, on the slope behind Meaux, even if the trees conceal them.