The Long Journey 1852

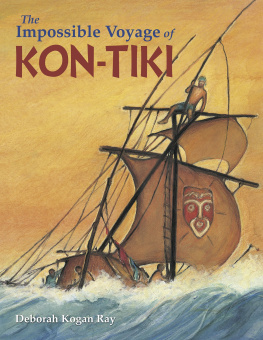

IT SEEMS STRANGE that so common a thing as sauerkraut could change the course of history and speed up Man's study of the earth's surface. But that is what happened. From the time of the early Phoenicians, Western Man had made remarkable progress in exploring the seas and mapping the land masses that were discovered all over the world, except in the South Pacific. There, the distances between land areas, much greater than anywhere else, defied the old-time sailing ships to traverse the seas without some means of conquering scurvy, that dreaded enemy of long voyages. It was not until the 18th century that this was finally overcome and sauerkraut was the means of laying low this ancient foe. British science demonstrated in the 1770's that scurvy could be prevented by stocking cabbage on every ship and requiring all on board to eat a little each day. Thus were the map makers and the ships' crews freed from the fear of long voyages.

The South Pacific is an ocean area of about 6,000,000 square miles, with thousands of small islands dotting its surface. There is about one square mile of land in each 600 square miles of ocean, even harder to find than a needle in a haystack! To add to the difficulty, most of the islands were low, not showing much above the ocean's surface, therefore not visible to a ship at any great distance. Only a few were lofty enough to be seen 100 miles away. It is not surprising, therefore, that the process of discovery and charting of these islands was very slow in that period of slow travel. The western group of islands, known as the Carolines, had been discovered in part by the Spanish in the 16th century, but most of this group remained uncharted until the beginning of the 19th. Ponape (pronounced Po-na-pay), one of the highest and largest of this group, had gone undiscovered until 1825, but forthwith there developed a lively commercial exploitation of the natives by American, English, and German traders and whalers.

When these natives first arrived on Ponape and from whence they came has never been established, for there were no written records of their past history, only legends. That they had been there a very long time was evident. It is thought by scientists who have studied this matter that they have been there for well over a thousand years. From whence did they come? This is quite un-unknown. Their legends speak of two canoes having come from the rising sun, filled with their people who settled here and became the progenitors of the present tribes. The "rising sun" concept points toward the east, perhaps to South America or some of the islands between Ponape and that distant continent. One theory held by anthropologists is that the Polynesian race came from South America in the 3rd or 4th century. Some hold that they came from the Asian side.

That these natives were not the original inhabitants of the islands is suggested by their legend that these first two canoe loads of new arrivals found a race of giants already established there. This legend has it that these giants had been quarreling and fighting among themselves and were almost completely exterminated when the newcomers arrived. It seems possible that there had been another people on the island. Sturges tells us in his journal that there are "remains of antiquity found in all parts of the island, and they are truly wonderful, consisting of stone walls, piers and vaults." The most remarkable of these are on several small islands near the weather harbor. On one there is an enclosure consisting of a double wall, the outer one 25 feet high and 15 feet thick. In the center of the enclosure is a stone vault in which several articles were found which indicate that the vault was once used for burial purposes. Next to the walls are elevated platforms, apparently for speakers. This suggests the idea that the place was a great temple where ceremonies for the dead were performed. Through the main wall is a gateway. Several openings near the ground were most likely for private entrance. Some have thought these walls were for defense and that they were the work of a more civilized people than now live here.

"I see no necessity for either," says Sturges, "as the whole would seem to be of use in the religious rites of the present natives, and there is nothing about them requiring any more skill than is found among these people. The only thing wonderful is that so much labor could have been performed without machinery. They are built of prismatic stones found on the north side of the island. Some of these prisms are 19 feet long and 3 feet thick. How such heavy masses could have been moved for a distance of 30 or 40 miles and then elevated into the walls is not easy to see. To complete so many structures, and so huge, must have required the labor of thousands, for ages. From the present natives we can get but little reliable information, but this is not strange, as they are slow to tell what they know to outsiders. They seem very ignorant of the past. There are still sacred rites performed around these antiquities and they are regarded as residences for Spirits. Almost every nook and corner has some peculiar rite connected with it.

"The natives tell us that these ruins were made by a race of giants once inhabiting the island. They point out some of the huge prisms as having been ear ornaments for these monsters.

"When [they were] built and [for] what, will never be determined but as monuments of former perseverance they will ever stand, and as faithful preachers proclaim man's short-lived glory. Alas! how these people have dwindled, how unlike what they were when they reared such mighty structures. Thus it is with every nation without the Gospel. They have no food for mind or body and from necessity must grow weak and die. No wonder the little remnant now here fail to identify themselves with their busy and numerous ancestors."

Missionary Sturges, after a long residence on the island among the natives, had the conviction that the "giants" were not a separate race but the same people in a stronger and more virile stage of their civilization. Their population had grown to large numbers and by sheer numerical strength the people, he thought, had been able to perform building feats that later, to their debilitated descendants seemed gigantic and superhuman. He points out that there was abundant evidence that Ponape must have had a population at one time of at least 20,000, and perhaps even as much as 30,000, but by 1850 it was down to about 10,000 and declining very rapidly. Infanticide and debauchery ( kava drinking) had for centuries been reducing their numbers and since 1825 some new diseases (especially syphilis), alcohol (new to the island), and prostitution had greatly accelerated the downward spiral.

Thus, we know that these islands had been discovered at least once and perhaps twice prior to the arrival of the white man, in 1825. Such discoveries had been by Stone-Age people, but the latest brought in a more advanced culture which at once precipitated an inevitable struggle for survival. This struggle had been going on for only 27 years when a new phase of it began with the arrival of a small company of Christian missionaries.

This company was destined to alter very greatly the struggle between the Stone-Age and the Iron-Age civilizations, guarding the former from the certain extinction toward which they were headed and already moving fast. Not only would it forestall their extinction but also it would conserve the good and valuable in this primitive race and help to mold them into a new people, able to take their place in the modern world.

The party of missionaries landed on Ponape in August, 1852, from a tiny sailing vessel that had been home to them for a number of weeks, since departing from Honolulu in July. They had touched at several other islands, where they had gone ashore for brief visits to gain a general idea of the situation into which they had committed themselves, but now on Ponape they had reached the end of the exploratory trip as they had planned it, and six of the ten were to remain and make this island their home. The other four would go back 300 miles to the island of Kusaie, where a second mission headquarters would be established. Then the ship would return to Honolulu.