First Mariner Books edition 1999

Copyright 1998 by the Estate of Henry Mitchell

Introduction copyright 1998 by Allen Lacy

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Mitchell, Henry, date.

Henry Mitchell on gardening / Henry Mitchell,

p. cm.

A Frances Tenenbaum Book.

ISBN 0-395-87821-7

ISBN 0-395-95767-2 (pbk.)

1. Gardening. 2. GardeningWashington Region. I. Title.

SB 455.3. M 574 1998

635.9dc21 97-35353 CIP

e ISBN 978-0-544-34356-6

v1.0714

The drawings by Susan Davis are used by permission.

Copyright 19831993 by Susan Davis.

The material in this volume originally appeared, in slightly different form, in the Washington Post.

FOR SUSAN DAVIS

Introduction by Allen Lacy

F OR A COUPLE OF DECADES the luckiest gardeners in the nation were those who subscribed to the Washington Post. Every Thursday they could turn to Henry Mitchells Earthman column to find out what was on his mind that week and what was going on in his garden in the District of Columbia. At a time when most garden writing was lethally dull and as impersonal as a committee report, Henry Mitchell was the great exception. He was often funny. He was always passionate, for his loves were many, although by the evidence he was especially enamored of bearded irises, roses, and dragonflies. He was endlessly quotable, whether he was telling his faithful readers that marigolds should be used as sparingly as ultimatums or reminding them that to go from winter to summer you have to pass March. Many of his readers clipped and saved his columns. I know, for friends in the Washington area often photocopied and sent them to me, knowing I would appreciate them. And I did. Henry Mitchell was the best garden writer in America, but he was more than that. He was a master essayist, with such a highly distinctive voice and style that his newspaper pieces didnt really need a byline. Two or three sentences were sufficient to make it clear that Mitchell had written them.

Those of us who were unable to read his Earthman columns when they first appeared have rejoiced that many of them have been collected in book form, first in The Essential Earthman (1981), then in One Mans Garden (1992), and now in Henry Mitchell on Gardening. These books will continue to find and delight new readers long into the coming century, for they are classics. I can make this claim without fear of being contradicted, for Henry Mitchell is no longer with us. Were he alive, he would almost certainly say, Classics? No, the books were just old newspaper columns, nothing more.

The three books give no clue that their author did virtually nothing to bring them into print, but his wife, Ginny, loves to set the record straight. When John Gallman of the University of Indiana Press approached Mitchell about publishing the columns that became The Essential Earthman, he had to go to Washington himself to collect the columns, and he, not the author, decided which ones would go into the collection and in what order. Later, when Ginny Mitchell found four unanswered letters from publishers expressing interest in another Earthman collection, her husband said, No one wants to read these things; theyre worthless. Ginny disagreed and offered to buy the rights, and the deal was made; Henry sold her the rights for one dollar. All Americans who love to read and who love to garden are the richer for this remarkable transaction.

I can think of no other writer so innocent of self-importance. There is an explanation, however. Henry Mitchell loved the English language as much as he loved roses and dragonflies, and he loved the works of William Shakespeare in particular. Shakespeare was the standard he judged himself by, and according to that standard he believed that he was only a journalist. Shakespeare was universal. Henry Mitchell considered himself to be merely local and parochial.

He was wrong about himself, of course. The truly universal turns out to be precisely the local and the parochialthe beastly days of deep winter or high summer, the marauding insect enemies, the orange marigolds that offend the eye when theyre planted right next to annual salvias of fire-engine red, the grace that comes on the air with the sweet and heady perfume of roses, the bright visitations of dragonflies. Henry Mitchell knew all these things and wrote of them. In his pages we can find themand him, and us.

Henry Mitchell was born in Memphis, Tennessee, the son of a prominent physician. He attended the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, but his career as a student was interrupted by military service during World War II. After the war he married Helen Virginia Holliday. For two years the Mitchells lived in Washington, where he began his newspaper career as a copy boy for the Washington Star. Later they moved to Memphis, where he became a columnist for the Commercial Appeal, a position he held for some twenty years. In 1970 he and his wife and their daughter and son moved back to Washington, where he was a reporter for the Washington Post.

Mitchells career as a garden writer began in 1973, when he began his weekly Earthman column. Three years later he undertook another column, Any Day, which dealt with any topic that struck his fancy. When he retired in 1991, he gave up that column, but he continued to write and delight his Earthman readers right up to his death in 1993.

No occupation is so delightful to me as the culture of the earth and no culture comparable to that of the garden.

Thomas Jefferson, 1811

JANUARY

When a Bloom Looms Large in Memory

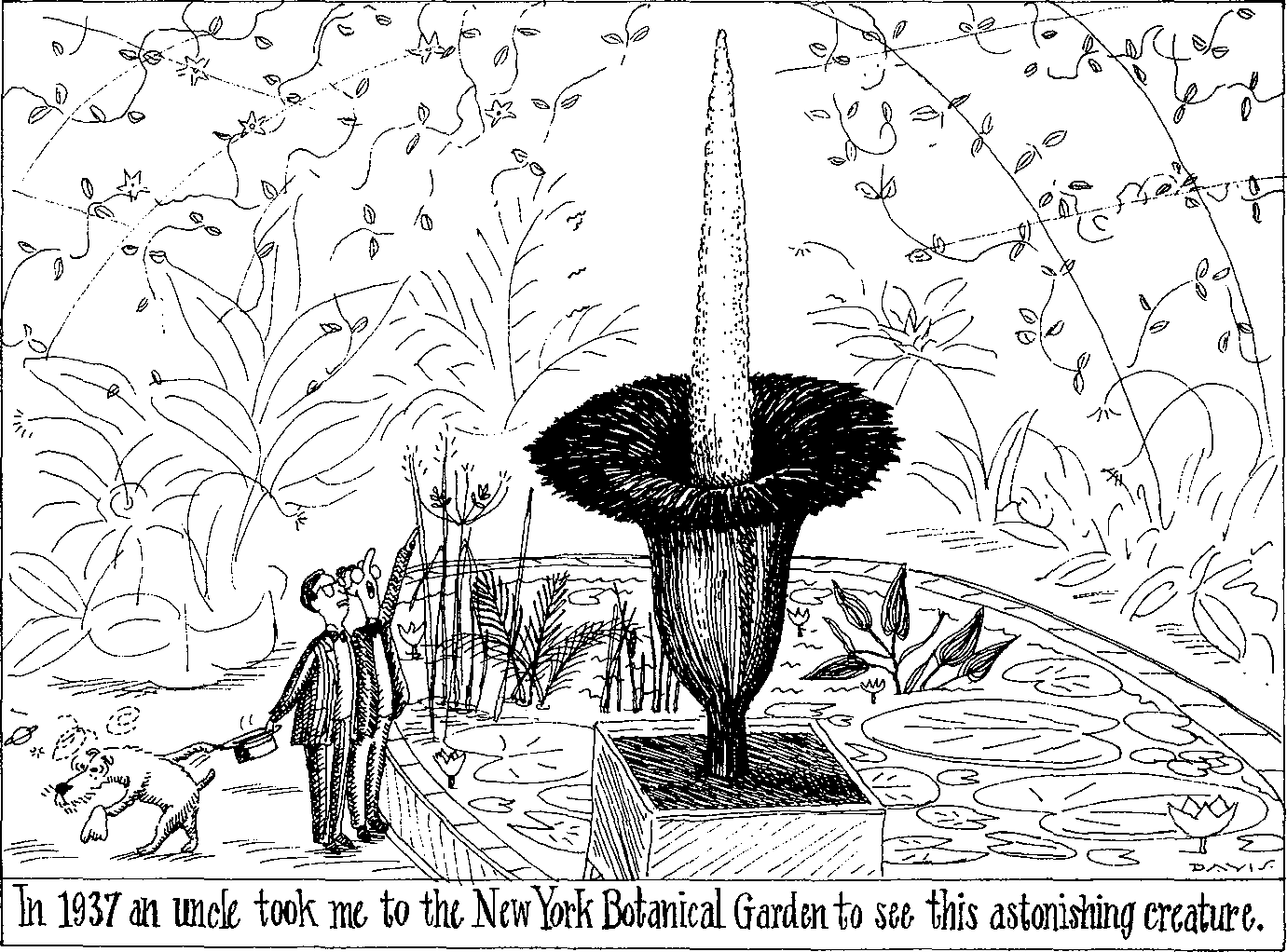

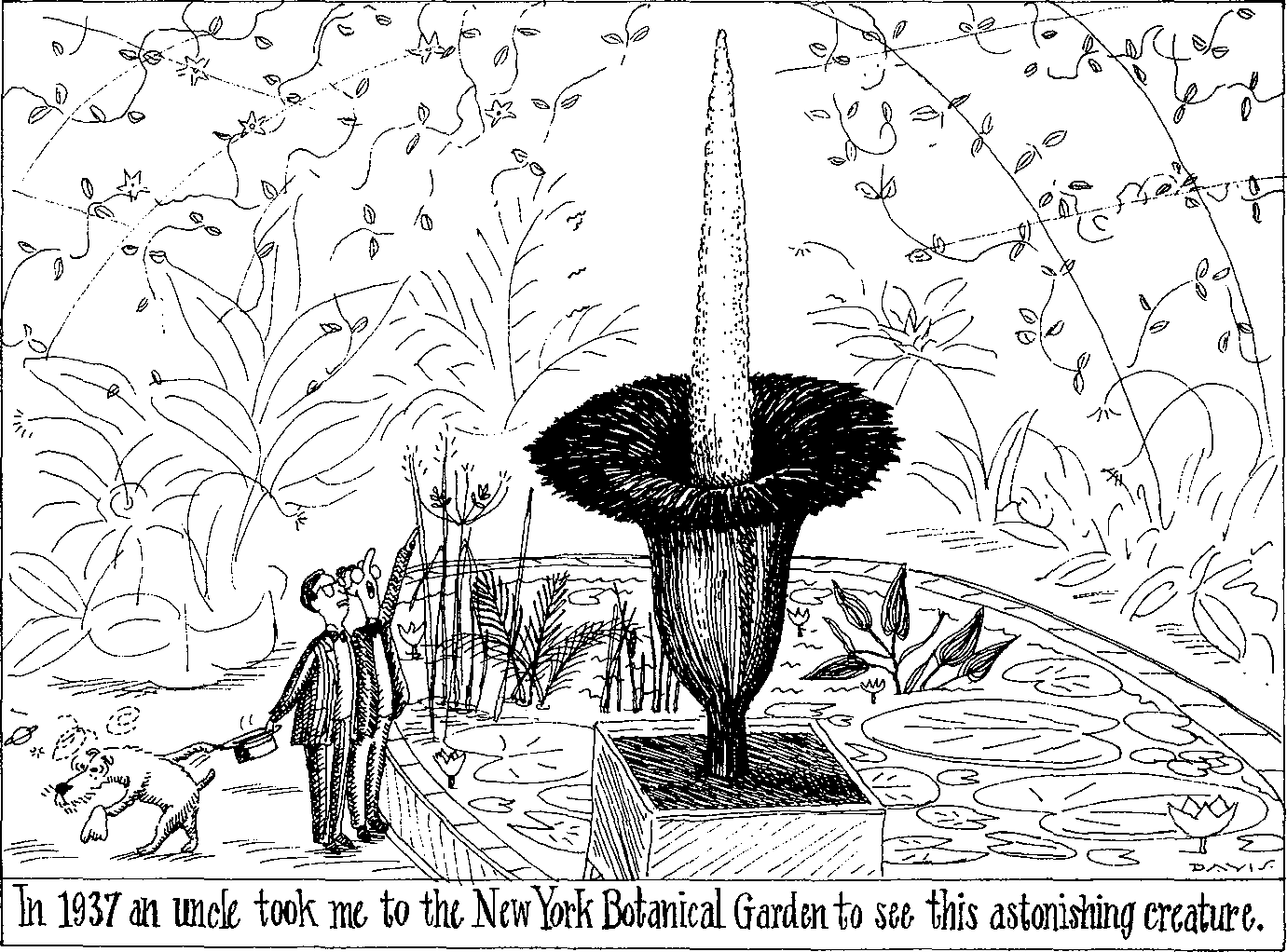

SOMETIMES A SINGLE FLOWER is enoughenough to be remembered clearly for more than half a centuryand while the flower I speak of, Amorphophallus titanum, is not for us regular steady gardeners, the point is still the same, that even in a city garden a single daffodil or water lily or iris or rose may be so beautiful that it is remembered always.

Once I had a bloom of unearthly beauty on a daffodil, Wedding Bell, and while that variety is hardly in the running for most beautiful daffodil, that one flower was glorious beyond reason. Other flowers of that variety were nice enough but nothing to go mad over.

There are individual roses and irises, individual blooms, that so far surpassed the usual and expected performance for that variety that I have never forgotten them. And the message here is that no matter how small the garden, it is large enough to produce a flower that the gardener will value in his memory long after he has forgotten whole fields of auratum lilies.

An allusion I once made to the great krubi, as the amorphophallus is called in its native Sumatra, inspired a number of gardeners to ask for more details about it. More than one person doubted that such a flower existed. Such is distrust in America today.

When I was a lad in 1937 an uncle took me to the New York Botanical Garden in June to see this astonishing creature. The garden had acquired a corm from Sumatra in 1932, and although it weighed sixty pounds it did not flower for five years.

I once spent a few hours with the late Thomas H. Everett, senior horticulture specialist at the garden. He was a remarkable man who single-handedly wrote the multivolume New York Botanical Garden Encyclopedia of Horticulture.

Next page