DEATH VALLEY NATIONAL PARK

Splendid Desolation

by

Stewart Aitchison

*****

SIERRA PRESS

Smashwords Edition

Copyright 2010 Sierra Press

*****

Smashwords Edition License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personalenjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away toother people. If you would like to share this book with anotherperson, please purchase an additional copy for each person. Ifyoure reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was notpurchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.comand purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard workof this author.

*****

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author and publisher wish to thank theNational Park Service including Coralee Corky Hays, Chief ofInterpretation, and Terry Baldino, Assistant Chief ofInterpretation, along with Charlie Callagan, Dale Housley, MarkNeuwald, and Vickie Wolfe. Special thanks also to Barbara Doram,Bill Helmer, and Pauline Esteves of the Timbisha Shoshone Villagewho were also helpful in providing information. Thanks, too, toJanice Newton, Executive Director of the Death Valley NaturalHistory Association, and her staff. Ann Kramer and Kaye Aitchisonreviewed the rough draft, and Nicky Leach, editor extraordinaire,smoothed out the rough spots.

*****

CONTENTS

*****

Death Valley, late afternoonview from Dante's View

In the cooldark, I drive up the road in the Black Mountains first graded backin the 1920s to provide tourists with a startling view of DeathValley. An early advertisement had boasted, You might enjoy a tripto Death Valley, now! It has all of the advantages of hell withoutthe inconveniences. A common poorwill, not the devil, flushes inthe headlights.

There is just a hint of day along the easternhorizon as I pull into the parking lot of Dantes View, located morethan 5,000 feet high in the Black Mountains. From there, Icarefully follow a primitive trail that climbs the ridge north ofthe parking area. The crunching of stone breaks the profoundsilence. Is it the movements along the great faults that createdthis landscape? No, just my boots hitting trail. Suddenly, a shrilltrilling sends a chill up my spine. Rattlesnake! Then a flash ofiridescent green and rose red sweeps bynot a snake but abroad-tailed hummingbird frantically looking for open blossoms.None here. And the hummer is gone.

A half-mile walk brings me to Dante Peak.Here I sit and wait. In the clear western sky, the pink boundarybetween night and day slowly descends until a snow-capped, distantpeak to the northwest catches fire. That particular summit is MountWhitney, at 14,491 feet the crown of the Sierra Nevada and thehighest point in the contiguous United States. The rising sunbegins to illuminate the top of Telescope Peak in the PanamintRange and reveals the yawning, shadowy graben in front of me. Thebare bones of the earth are exposed, colorful, naked scarps andundulating foothills. With no trees, buildings, or familiarobjects, the scale is deceptive. Badwater Basin, the lowest pointin the Western Hemisphere, is an unfathomable vertical mile belowme. To the south are the Avawatz and Owlhead Mountains. To theright of the Owlheads is Wingate Wash, used by some of the 1849argonauts to escape Death Valley and later by the legendarytwenty-mule team wagons. North are the Cottonwood Mountains on thewest and the Grapevine and Funeral Mountains on the east side ofthe great valley. Behind me, backlit against the risingbright-orange sun, are the Spring Mountains over in Nevada.

I snooze but awake later hot and sweaty,cotton-mouthed and exposed skin already glowing red. Several turkeyvultures teeter by me, broad dark wings held in the characteristicdihedral, drifting ever higher on a rising thermal. I move toconvince them and myself that I am not dead. The sunlight hits theglistening white saltpan of Badwater. A persistent tale says thatthe Paiute cursed Death Valley with the name Tomesha,ground afire, an appropriate name for sure, but simply acorruption of Tumbisha, the Timbisha Shoshone village at the mouthof Furnace Creek and actually closer to meaning red ochre.

In the harsh midday light, the mountains arebrooding masses of burnt iron. Most have no introductory hills, themountains rising abruptly out of the flat, burning basin. Fromhere, no plant life is discernible on the valley floor, but I knowthat on this spring morning desert gold, brown-eyed eveningprimrose, purple mat, and gravel ghost are in their glory.

Is that a dust devil twirling in theshimmering heat of Cottonball Basin? Do I see the long, dark lineof a laboring mule team? Are those tall wagons loaded with boraxlooming in the haze? See the dusty figure high on the wagon box?Can I hear the rumble and chuckle of the great wheels? The creak ofharnesses? The jangle of chains? The fiery voice of the teamsterraised in encouragement? Do I see ghostly silhouettes of severallanky camels left over from the California-Nevada Border Survey of1861 or the re-enactment done 121 years later? Perhaps it is theLost Montgomery Train, a mythical horror story that grew over thedecades from rumor and retelling until one version had an entireband of 400 emigrants perishing in the valley in the 1800s andtheir bones scattered for miles by the coyotes and buzzards. Thetwenty-mule team and the bleached skeletons of lost souls are iconsof Death Valley but, like so many things about the valley, it isdifficult to separate the illusions, mirages, and dreams fromfact.

Across the valley, I can barely make outHanaupah Canyon, cut into the dry flank of the Panamint Range justbelow Telescope Peak. Thats where one dreamer, Alexander ShortyBorden, hand-built a 10-mile road to his lead and silver diggingsback in the 1930s. Like so many of the mining ventures in the area,the cost to transport the ore to a smelter proved more than the orewas worth. Shorty eventually abandoned mining and lived offhandouts from passing tourists. Today, the flowing sweet streamlined with willow, mesquite, and wild grape masks the lost dreamsof the old prospector and beguiles the hiker who climbs into thiscanyon sanctuary.

I take a sip of warm water from my canteenand retreat down the mountain to my air-conditioned car. Ill cookif I wait here for late afternoon, when long golden rays ofsunshine will turn the mountains into radiant ships on a calm sea.Dantes Viewindeed.

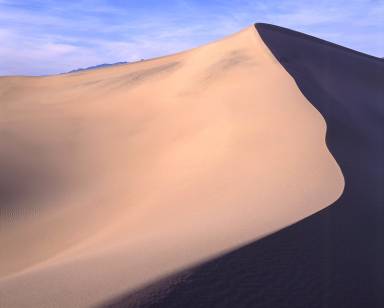

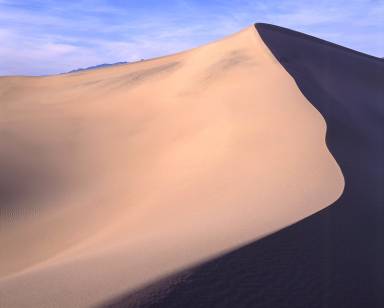

Sunset, Mesquite Flat anddistant mountains

Death ValleyNational Park is a land of sailing rocks, musical dunes, sublimevistas, and tall tales. Lets look at some of the dry facts:ecologically, Death Valley lies within the very northern part ofthe Mojave Desert and is also part of the Great Basin, a regioncovering much of the intermountain West. In the Great Basin riversand streams do not flow out to an ocean but into valleys or basinswhere the water sinks, evaporates, and/or becomes a saline lake.Death Valley and its surrounding mountain ranges are also withinthe geologic province called the Basin and Range, where stretchingand large-scale faulting of the earths crust has produced a seriesof roughly parallel, north-southtrending valleys andranges.

By the 1920s, Death Valleys scenic wonderswere becoming known to the outside world, and some mine operatorsthought that there might be more gold in the pockets of touriststhan in the rocks of Death Valley. One former borax mining companyemployee, Stephen Mather, became the first director of the NationalPark Service and a strong promoter of setting the valley aside as anational park. Furthermore, popular books and articles in theSaturday Evening Post boosted visitation, and on September 30,1930, a new radio show called, Death Valley Days aired. Matherssuccessor as park service director, Horace Albright, convincedPresident Herbert Hoover to sign an executive order temporarilywithdrawing Death Valley from further exploitation. During his lastdays in office in 1933, Hoover signed the proclamation establishing1,600,000 acres as Death Valley National Monument.

Next page