Marcus Tanner is an author and journalist, specialising in Central and Eastern Europe. He was the Independents Balkan correspondent from 1988 to 1994 and was subsequently Assistant Foreign Editor. He is the author of Croatia: A Nation Forged in War; The Raven King: Matthias Corvinus and the Fate of His Lost Library; The Last of the Celts; Irelands Holy Wars: The Struggle for a Nations Soul, 15002000 and Ticket to Latvia: A Journey from Berlin to the Baltic.

Albanias

MOUNTAIN QUEEN

Edith Durham and the Balkans

MARCUS TANNER

Published in 2014 by I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada

Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

Copyright 2014 Marcus Tanner

The right of Marcus Tanner to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every effort has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

ISBN: 978 1 78076 819 9

eISBN: 978 0 85773 504 1

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

ILLUSTRATIONS

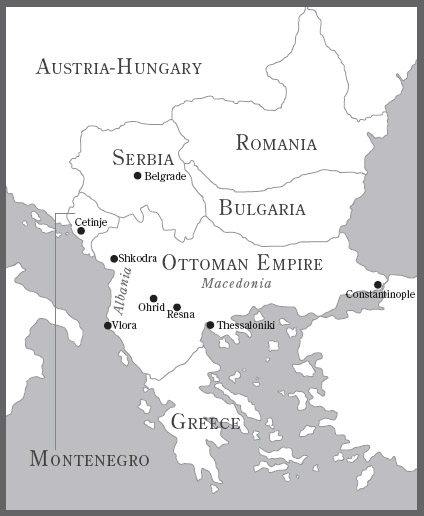

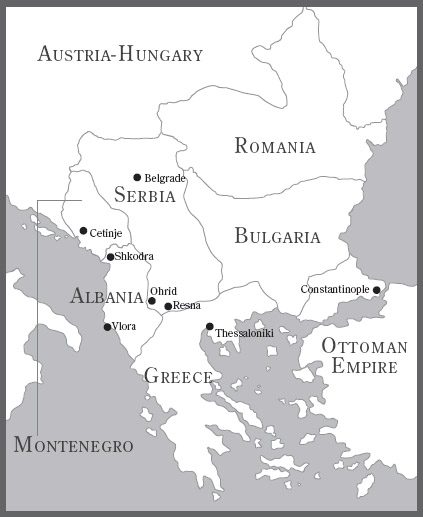

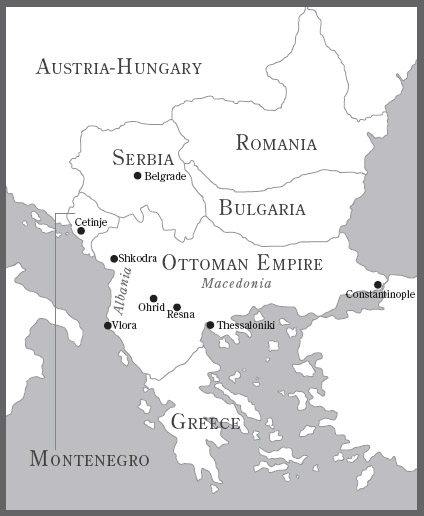

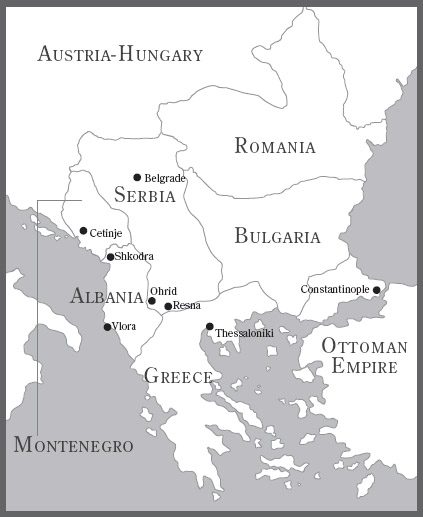

Maps

Plates

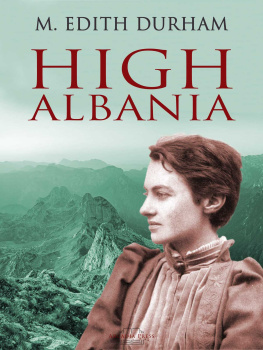

Edith Durham as a young woman

Not to be reproduced without the written permission of the Durham family

King Nikola of Montenegro and his family

Mary Evans Picture Library

King Petar of Serbia

Public domain

Ismail Qemali and the declaration of Albanian independence, November 1912

Public domain

William of Wied

Public domain

King Zog of Albania

Public domain

Aubrey Herbert

Public domain

Henry Nevinson

National Portrait Gallery, London

Robert Seton-Watson

Courtesy of the British Academy

Rebecca West

National Portrait Gallery, London

Albanian tribesmen

Public domain

IMRO leaders in 1903

Public domain

Shkodra in 1897

Public domain

Ohrid circa 1900

Photographed by M.E. Durham. RAI 3799. Courtesy of the Royal Anthropological Institute, London

Cetinje in 1895

Public domain

Resen

Drawn by M.E. Durham. H 388. Courtesy of the Royal Anthropological Institute, London

Macedonian freedom

Punch Limited

Edith Durham School in Tirana

Public domain

NOTE ON SPELLING

I T IS HARD to be entirely consistent about spellings in a region where so many places have changed their names over the past century, or are spelled in different ways, each sending a different message as to which community owns it. I have opted to use modern names and spellings for most place names, as these probably are now the best known. Thus: Edirne, not Adrianople; Bitola, not Monastir; Thessaloniki, not Salonika; and Drres, not Durazzo. For the same reason: Kosovo the internationally recognised name of the republic not Kossovo (the old-fashioned English spelling), or Kosova, as Albanians usually call it; and Metohija Serbias preferred expression. I have made an exception for Constantinople, as this term remains familiar to everyone. Regarding personal names, generally I have used modern spellings rather than English translations. Thus: Petar, not Peter, of Serbia; and Nikola, not Nicholas, of Montenegro. I have stuck with William of Wied, not Wilhelm, because that is how he is normally styled in English. Likewise, on the grounds of familiarity, Nicholas II of Russia and Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary rather than Francis Joseph or Franz Josef. With Albanian and Ottoman names, I have followed the same principle. Thus: Essad Pasha Toptani, not Esad Pashe; and Ahmed, not Ahmet, Zogu. Both Abdul Hamid and Abdulhamid are commonly used in English for the Ottoman Sultan. I have opted for Abdulhamid.

Introduction

I WAS STAMPING MY feet outside a freezing courthouse in the grim town of Mitrovica in northern Kosovo when I first heard of Edith Durham. A rookie reporter, I had been sent there by a British newspaper in October 1989 to cover the trial of Azem Vllasi, the recently arrested leader of the League of Communists of Kosovo in what then was the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia. Inside that federation, in which Kosovo was imprecisely linked to next-door Serbia, Serbias assertive new leader, Slobodan Miloevi, had resolved to scrap Kosovos autonomy and absorb the province into Serbia. With a view to frightening the mainly Albanian population of Kosovo into submission, he was having their leader arrested.

Vllasi, a saturnine man with vaguely matinee-idol looks, was up for the typical communist-era, catch-all charge of counter-revolutionary nationalism and separatism. Outside the chilly courthouse in Mitrovica we didnt see it, but it was the beginning of the end of the Yugoslav state that the Entente powers had helped to set up 70 years earlier, following the end of World War I.

The Serbs, a shrinking and embittered minority in Kosovo, were all for sending Vllasi to prison, if not to the scaffold.not realise was that by violently unravelling this knot with hard yanks, they would end up unravelling all the other cords that bound Yugoslavia together. The conflict that began in Kosovo in the mid-to-late 1980s spread from one republic to another like fire through thatch.

Vllasi, meanwhile, was on trial in Titova Mitrovica Titos Mitrovica, as it was styled in homage to the late Yugoslav strongman. Titos or not, the town was grim even by the undemanding standards of the Balkans. Mitrovica had been an industrial centre of some significance in communist Yugoslavia, lying close to the important Trepa zinc and lead mines. But, by 1989, nine years had passed since Tito had expired in a clinic in Slovenia, and the industrial and economic boom he had overseen was over. Yugoslavia had been in the grip of an economic crisis since the oil crisis of 1983. Now these economic strains showed in the fractious relations between the six republics and in the drawn, flyblown appearance of towns like Mitrovica.

Jobless or semi-jobless Serbs and Albanians sat stony-faced, puffing away on their cigarettes and sipping grainy black coffees in separate but equally grey cafes that faced one another on the dilapidated main square. The Albanians complained bitterly of the arrest of Vllasi and of Miloevis plans to do away with the autonomy that Tito had granted the province at the end of World War II.sides of the ethnic divide had hurled onto the banks of the Ibar, the river that bisected the town. Many still lay forlornly on the river bank, smashed to pieces and rusting away slowly.

It was while I was waiting outside the courthouse for news to emerge of Vllasis trial that a journalist colleague suggested I take a look at his copy of a book by Edith Durham

Next page