THE MODERN

BALKANS

A History

RICHARD C. HALL

REAKTION BOOKS

For Audrey, as ever

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2011

Copyright Richard C. Hall 2011

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

MPG Books Group

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Hall, Richard C. (Richard Cooper), 1950

The modern Balkans : a history.

1. Balkan Peninsula History 19th century.

2. Balkan Peninsula History 20th century.

1. Title

949.6-DC22

eISBN: 97481780230061

Contents

Introduction

T he Balkan Peninsula of Southeastern Europe was the first part of the continent to achieve civilization. In ancient times it formed an important link between eastern Mediterranean and European civilizations. After the Middle Ages, however, the region seemed to fade into itself. First Orthodox culture and then Ottoman rule isolated the region from the rest of Europe.

Only at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries did the region again come into contact with the outside world. Especially important were contacts with Western Europe. As a result of these contacts the peoples of Southeastern Europe struggled to emulate the more economically and politically developed Western European states. These efforts led to much instability and war during the twentieth century. The Communist interlude also isolated the region from the rest of Europe to a degree, but imposed peace. Cold War concerns, however, increased Western interest in the region.

The end of Communism brought to the region the hope of restoration of its European identity. It also brought violence. Romania underwent a short but bloody revolution. The situations in Albania and in Yugoslavia compelled the European Union, the United Nations and NATO to intervene in order to establish stability. Only Bulgaria escaped bloodshed during this transition.

With the onset of the nineteenth century, Southeastern Europe began to achieve recognition as a distinct region of the continent. This recognition was based on the singularities of the area. Its geography was more complicated, its peoples more exotic and its politics more arcane than the rest of Europe. It seemed to have a penchant for mystery and violence. Southeastern Europe appeared to be a part of another world, often referred to as The Balkans. The assocition of the name Balkan with obscurity and violence became a clich.

A variety of works on the region appeared in English at the beginning of the twentieth century. Most of these emphasized the distinct characteristics of the Balkans. A good example is the American historian Ferdinand Schevills History of the Balkans from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. It is particularly good on the interaction of the region with the rest of Europe.

Southeastern Europe is now undergoing a process of integration with the rest of Europe. For this reason the terms Balkans and Southeastern Europe will be used interchangeably to refer to the region throughout this book. Recent studies of the region, such as John R. Lampes Balkans into Southeastern Europe and Andrew Baruch Wachtels The Balkans in World History, emphasize that the region is now integrating with the rest of Europe. Now, with most of the countries members of NATO and the European Union, integration offers the region another opportunity for peace and prosperity.

one

Geography

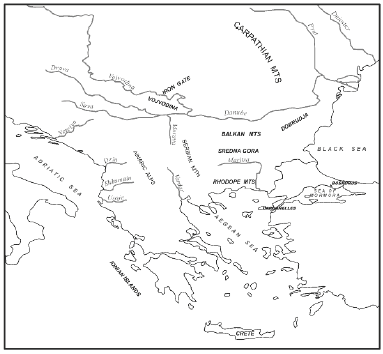

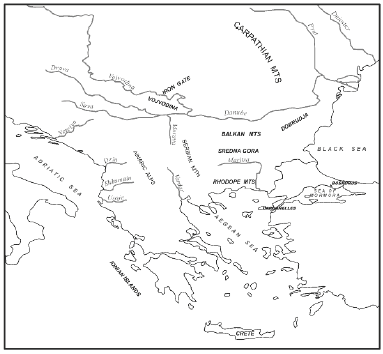

T he natural setting of any region is a significant factor in understanding the course of human events over time. Natural setting has played a particularly important role in the history of Southeastern Europe. Southeastern Europe is a peninsula, often termed the Balkan Peninsula. Wide in the north, it tapers down to the Peloponnese, itself a peninsula, and from there to a series of rocky islands off its western, southern and eastern coasts. The main groups of these islands are the Ionian Islands in the Adriatic and Crete and the Cyclades in the Aegean. Rocky fragments of the Dinaric Mountain chain span the entire coastline of the Adriatic Sea from Istria to the Peloponnese. The construction of the Corinth Canal across the narrow isthmus which links the Peloponnese to the rest of mainland Greece in 1893 provided a direct water link between the Aegean and Ionian Seas. There are significant bodies of water on three sides of Southeastern Europe. In the west is the Adriatic Sea and to the south is the Aegean Sea; these two bodies of water are arms of the much larger Mediterranean Sea. To the east is the Black Sea, a self-contained body of water, accessible to the Mediterranean only through the narrow passage way of the Dardanelles, Sea of Marmara and the Bosporus. The two large islands in the eastern Mediterranean, Crete and Cyprus, although located at some distance from the mainland, have both played important roles in the political history of the region.

Mountains are another defining characteristic of Southeastern Europe. Almost 70 per cent of the region is mountainous. The mountains impose an irregular and rugged topography over the entire region. Two main mountain systems dominate the region. The first is a generally barren limestone alpine system often called karst. These mountains generally run from northwest to southeast along the entire length of the western portion of the peninsula. They are known as the Dinaric Alps in Croatia and Bosnia, the Albanian Alps in Albania and the Pindus Mountains in Greece. These mountains often run right down to the Adriatic Sea. Along the Dalmatian and Greek coasts there are many islands resulting from the continuation of the mountain system under sea. Crests of this system generally reach 1,800 m (6,000 feet). In some areas, notably the Albanian Alps in northern Albania and the Pindus Mountains in northwestern Greece, the peaks reach as high as 2,400 m (8,000 feet). Along the easterly edge of these mountains in Albania, Macedonia and Greece there are a number of fresh-water lakes. These include Lake Scutari, which lies between Albania and Montenegro, Lake Ohrid between Albania and Macedonia, and Lakes Prespa and Doiran between Greece and Macedonia.

Balkan geography.

The other mountain system is more easterly. In Romania, the thickly forested Carpathians impose a reverse S-shape on the northeastern region The Bulgarians themselves call the Balkan Mountains the Stara Planina, or Old Mountains. There are numerous points of access across these mountains. The best known of these is Shipka Pass, which was the scene of an important battle in the nineteenth century. A smaller range, the Sredna Gora (Middle Mount ains), parallels the Balkan Mountains to the south. This is really just a line of hills arising from the Thracian Plain. Often the forest cover is absent in the Balkans and Sredna Gora. The southern Bulgarian mountain system is known as the Rhodope Mountains. Peaks there, such as 2,289 m (7,510 foot) Vitosha, located directly south of Sofia, and Rila, the highest of these mountains at 2,925 m (9,596 feet), can retain some snow all year round. Parts of the mountain forests remain in the Balkan Mountains. The Carpathians, the highest of the southeastern mountains and the Rhodopes still retain most of their forest cover.