Table of Contents

TO DIMITRI GONDICAS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am deeply grateful to Phil Nord for allowing me to spend two years at Princeton, where I have been blessed with an extraordinary group of friends and colleagues. My thanks in particular for their comments, advice, guidance and criticism in connection with this project to: Peter Brown, Marwa Elshakry, Laura Engelstein, Bill Jordan, Tia Kolbaba, Liz Lunbeck, Arno Mayer, Ken Mills and Gyan Prakash. Molly Greene and Heath Lowry patiently introduced me to Ottoman realities; Polymeris Voglis and Dimitris Livanios made many valuable suggestions and criticisms. In London, Peter Mandler gave me advice and assistance. Johanna Weber offered huge encouragement, and challenged my prose line by line: my debt to her is beyond words. My thanks too to Nicholas Dirks and Tony Molho for opportunities to try out portions of my argument at Columbia and Brown Universities, and to Fergus Bremner for his refreshing and nourishing ideas. I am indebted to the British Academy and the Leverholme Trust for their generous support of my work. Over many years, Dimitri Gondicas has turned the Program in Hellenic Studies at Princeton into a major center for research and intellectual exchange. To him, as token of my long-standing gratitude, admiration and deep affection, I dedicate this book.

Modern Library Chronicles

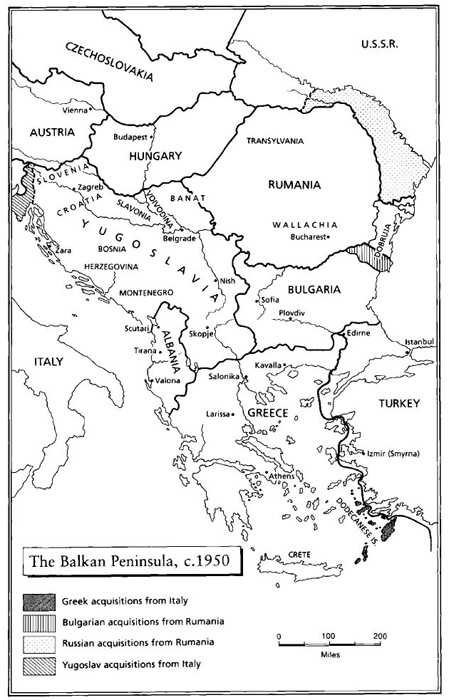

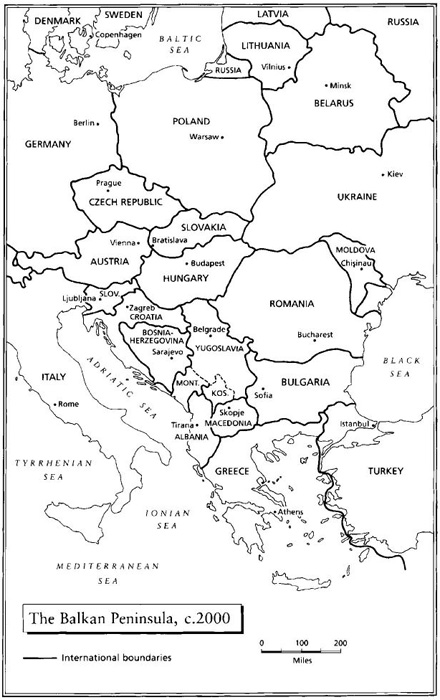

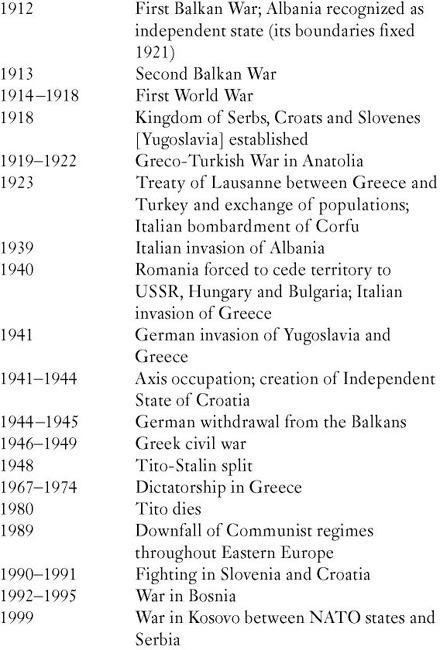

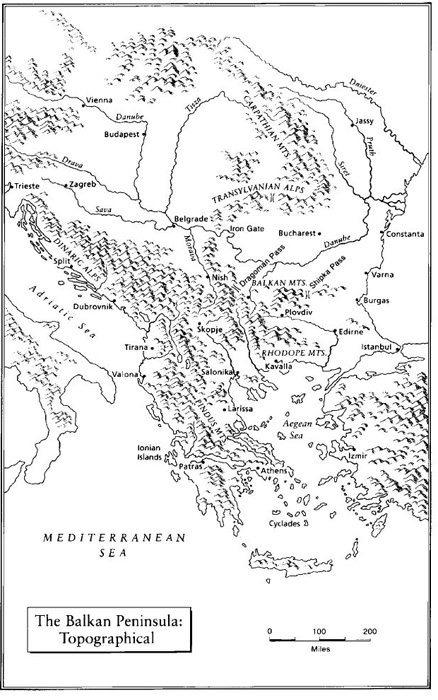

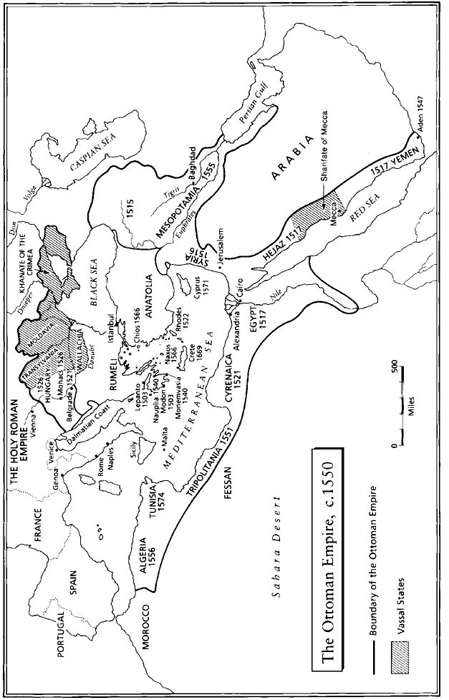

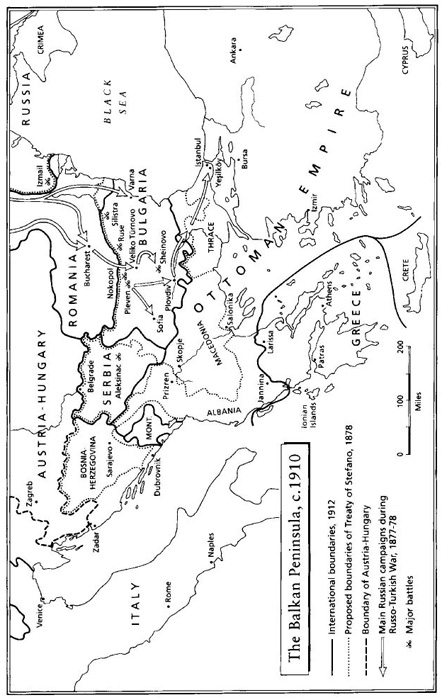

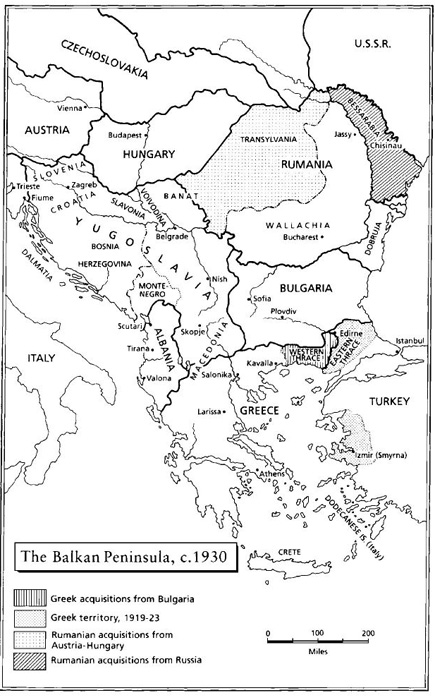

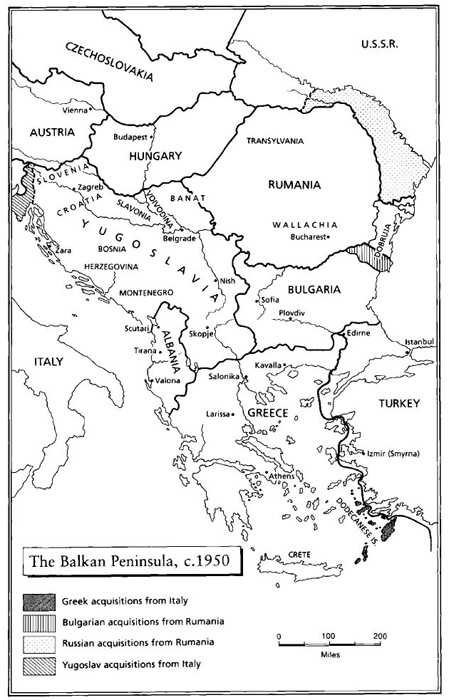

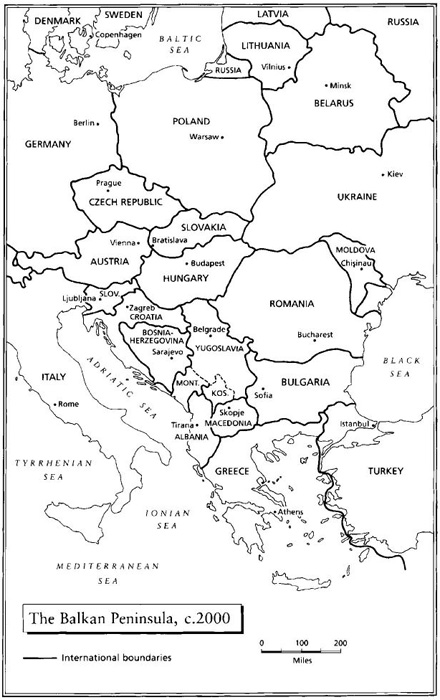

MAPS

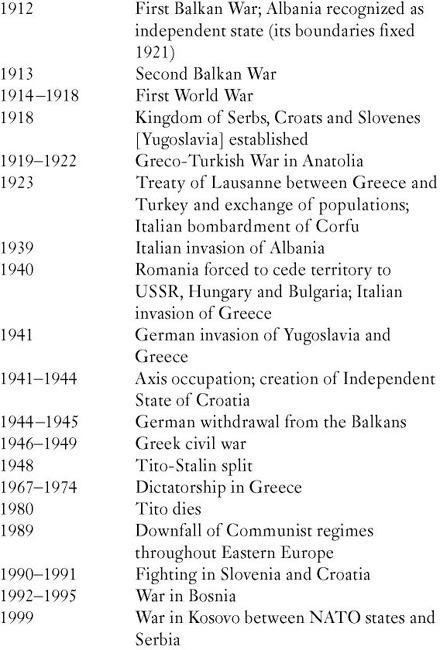

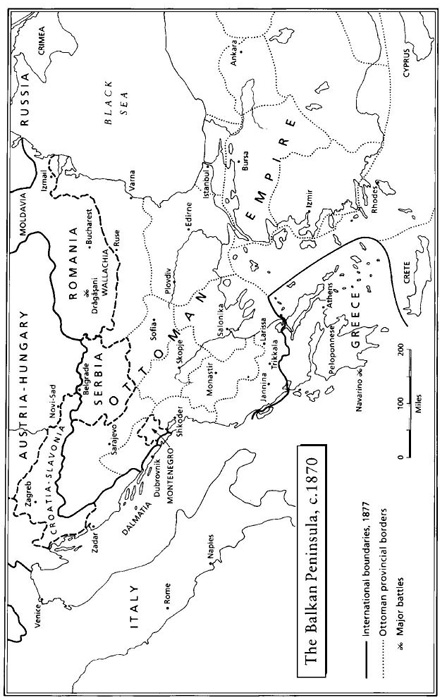

CHRONOLOGY

Please note that some dates are approximate or speculative

INTRODUCTION: NAMES

The reputation, name and appearance, the usual measure and weight of a thing, what it counts fororiginally almost always wrong and arbitrary... all this grows from generation unto generation, merely because people believe in it, until it gradually grows to be part of the thing and turns into its very body. What at first was appearance becomes in the end, almost invariably, the essence and effective as such. FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE 1

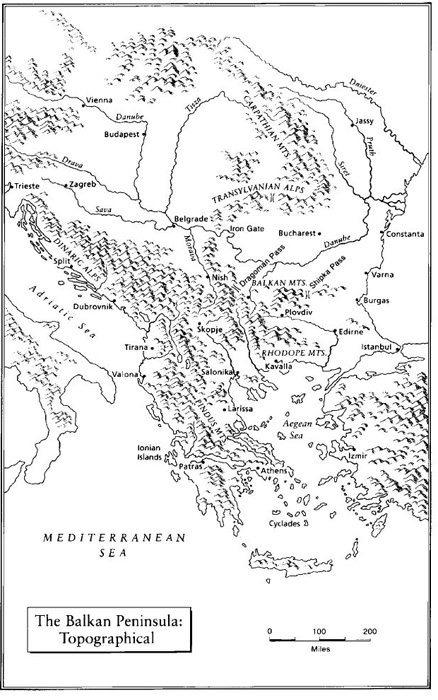

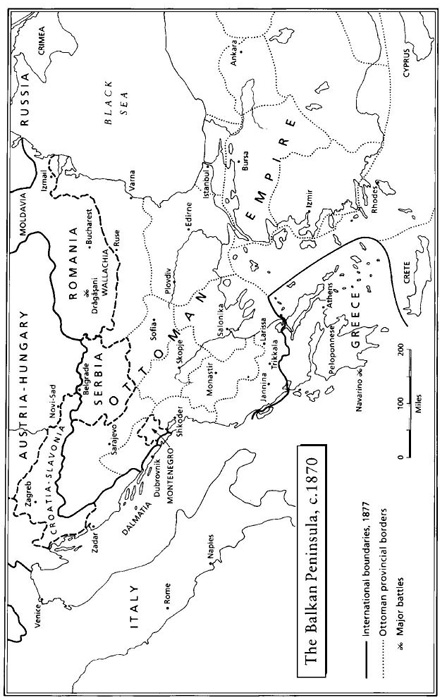

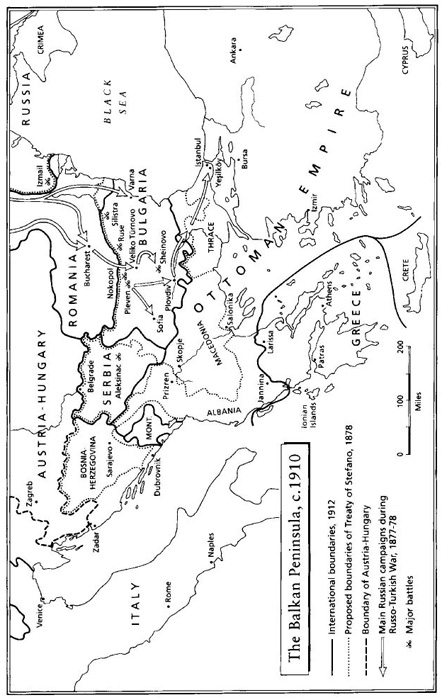

At the end of the twentieth century, people spoke as if the Balkans had existed forever. However, two hundred years earlier, they had not yet come into being. It was not the Balkans but Rumeli that the Ottomans ruled, the formerly Roman lands that they had conquered from Constantinople. The Sultans educated Christian Orthodox subjects referred to themselves as Romans (Romaioi), or more simply as Christians. To Westerners, familiar with classical regional terms such as Macedonia, Epirus, Dacia and Moesia, the term Balkan conveyed little. My expectations were raised, wrote one traveler in 1854, by hearing that we were about to cross a Balkan; but I discovered ere long that this high-sounding title denotes only a ridge which divides the waters, or a mountain pass, without its being a necessary consequence that it offer grand or romantic scenery.2 Balkan was initially a name applied to the mountain range better known to the classically trained Western traveler as ancient Haemus, passed en route from central Europe to Constantinople. In the early nineteenth century, army officers like the Earl of Albemarle explored its little-known slopes. The interior of the Balcan, wrote a Prussian diplomat who crossed it in 1833, has been little explored, and but a few, accurate measurements of elevation have been undertaken. Little had changed twenty years later, when Giacomo August Jochmuss Notes on a Journey into the Balkan, or Mount Haemus was read to the Royal Geographical Society. It was across these mountains that the Russian army advanced on Constantinople in 1829 and again in 1877. The crossing of the Balkans, wrote the author of a popular history of the Russo-Turkish War of the latter year, must be reckoned one of the most remarkable achievements of the war.3

By this time, a handful of geographers had already stretched the word to refer to the entire region, mostly on the erroneous assumption that the Balkan range ran right across the peninsula of southeastern Europe, much as the Pyrenees demarcated the top of the Iberian. In the eighteenth century, geographical knowledge of the Turkish domains was very vague; as late as 1802, John Pinkerton noted that recent maps of these regions are still very imperfect. Most scholars, including the Greek authors of the earliest study from the area, used the much commoner term European Turkey, and references to the Balkans remained scarce long into the nineteenth century. They are, for instance, absent in the writings of the savant Ami Bou, whose minute exploration of the entire region La Turquie dEurope of 1840set standards of accuracy and detail not matched for generations.4

Nor before the 1880s were there many references to Balkan peoples either. The world of Orthodoxy encompassed Greek and Slav alike, and it took time for ethnographic and political distinctions between the various Orthodox populations to emerge. In 1797, the revolutionary firebrand Rhigas Velestinlis, inspired by the French Revolution, predicted the downfall of the Sultan and proclaimed the need for a Hellenic Republic in which all the peoples of Rumeli, Asia Minor, the Archipelago, Moldavia and Wallachia would be recognized as citizens, despite their different races and religions. In Rhigass vast future republic, Greek was to be the language not only of learning but also of government. As late as the 1850s informed commentators were still scoffing at superficial observers, who consider the Slavonic races as Greek because the great majority of them are of the Greek religion. Even the German scholar Karl Ritter proposed calling the whole region south of the Danube the Halbinsel Griechenland (Greek peninsula). Till quite lately, wrote the British historian E. A. Freeman in 1877, all the Orthodox subjects of the Turk were in most European eyes looked on alike as Greeks. 5

Next page