Mark Mazower

WHAT YOU DID NOT TELL

A Russian Past and the Journey Home

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in the United States of America by Other Press, LLC 2017

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2017

Copyright Mark Mazower, 2017

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover image: Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock Photo

ISBN: 978-0-241-32137-9

For Selma and Jed

and for their cousins

Nina and Clara

Rachel, Cleo and Nicholas

Max, Seth and Elliot

INTRODUCTION

On West Hill

I thought I knew Dad well, but the day he died I began to realize how much of his life was unknown to me. We had come back home from the hospice and somebody asked what kind of funeral his parents had had. As none of us was sure, I did what my historians training and instinct suggested: I went to the archive. Upstairs in the wardrobe were his boxes of family papers, and on one of them he had written: Diaries, 19411996. I climbed on a chair and fetched it down and sat with it on my parents bed. I am pretty sure it was the first time I had opened it.

I had always felt close to Dad, and when my brothers and I were growing up, he had been the most comforting of presences. Once, I remember, we were driving through the Cotswolds, just he and I. It was a spring day, and I must have been twelve or thirteen. We were looking at houses because he and Mum were thinking about buying a weekend cottage. The map was spread out on my lap, and I recall feeling proud that he was relying on me for directions. He drove and I gazed out of the window as the fields flashed past, comfortable in our easy silence and mutual trust.

A comfortable silence is not an impenetrable one. Dad had not been a talkative man, and he shied away from the personal like a nervous horse. Difficult questions could elicit a faint smile before he responded. But we could ask him anything, and he would tell us stories about his childhood and his parents. Some years before his death, he and I decided to get these stories downhe was a grandfather by then and time was passingso we went to his room at the top of the house and I switched on the tape recorder. Our conversations ran over several afternoons, and I dont remember that there was anything he refused to talk about. The limits were really inside me: I felt inhibited about raising some things with him, and there were many others it never occurred to me to ask.

Inside the box there were a couple of old address books and half a centurys worth of his Letts pocket diaries, neatly arranged in chronological order. He had used them mostly to jot down appointments and I soon found the information we needed. There were no intimate confessions or emotional outpouringsno surprise thereand you could have counted on the fingers of one hand the points at which Dad had recorded a mood or feeling. Yet those resolutely unintrospective pages spoke after their fashion, and as I read on, I slowly began to piece together the pattern of daily movements and social contacts that had characterized his life.

He had grown up in the North London neighborhood of Highgate and the diaries testified to his enduring attachment to it. At the start of January 1942, when he noted in his Schoolboy Diary that he saw Daddy off in Waterlow Park, he was just sixteen. He was about to return to the school he was attending in Somerset as an evacuee; his rapidly aging father was making his way through the bombed-out city to his wartime job in postal censorship. A decade later, Oxford and military service were behind him, and the year his father died was also the year his cousins visited from Paris and he took the children for a walk on the Heath. Children did not mean my brothers and .

When they became parents, Mum and Dad started filming us, and as we grew older a favorite treat on wintry weekend afternoons was to get out the projector, draw the curtains, and watch ourselves as toddlers: Daves first steps, tottering towards the camera across the sands in Devon; Ben in the pram in our back garden; Jony on the climbing frame. One of their earliest efforts dates from the summer of 1958. It is a sunny day and Mum must have been holding the camerathey had borrowed it from a friend. They are on Hampstead Heath for a picnic and as usual they have laid the tartan rug on the ground because the grass is often a little damp even in July and August. Dad is on his back, holding me above his head: He is full of life and looks strong and happy, much as I remember him throughout my childhood. Yet when I freeze the frame, I notice something else now, lurking in the distance: There behind him, across the ponds and above the tree line, is the spire of St. Michaels at the top of Highgate West Hill. It marks with a strange precision the very spot where I would wait each day to catch a cab to visit him in hospital half a century later, in the last few months of his life.

It was the summer of 2009 and a sabbatical had brought me back to London. Shortly after I arrived, his health had taken a turn for the worse. Not having a car, I used to walk up Highgate Hill and wait there for a taxi. The autumn was unusually mildas I remember, there were hardly any rainy daysand the stroll allowed my mind to float away from the image of Dad lying in his ward towards the things he liked to talk about: the war, his childhood, history, Russia.

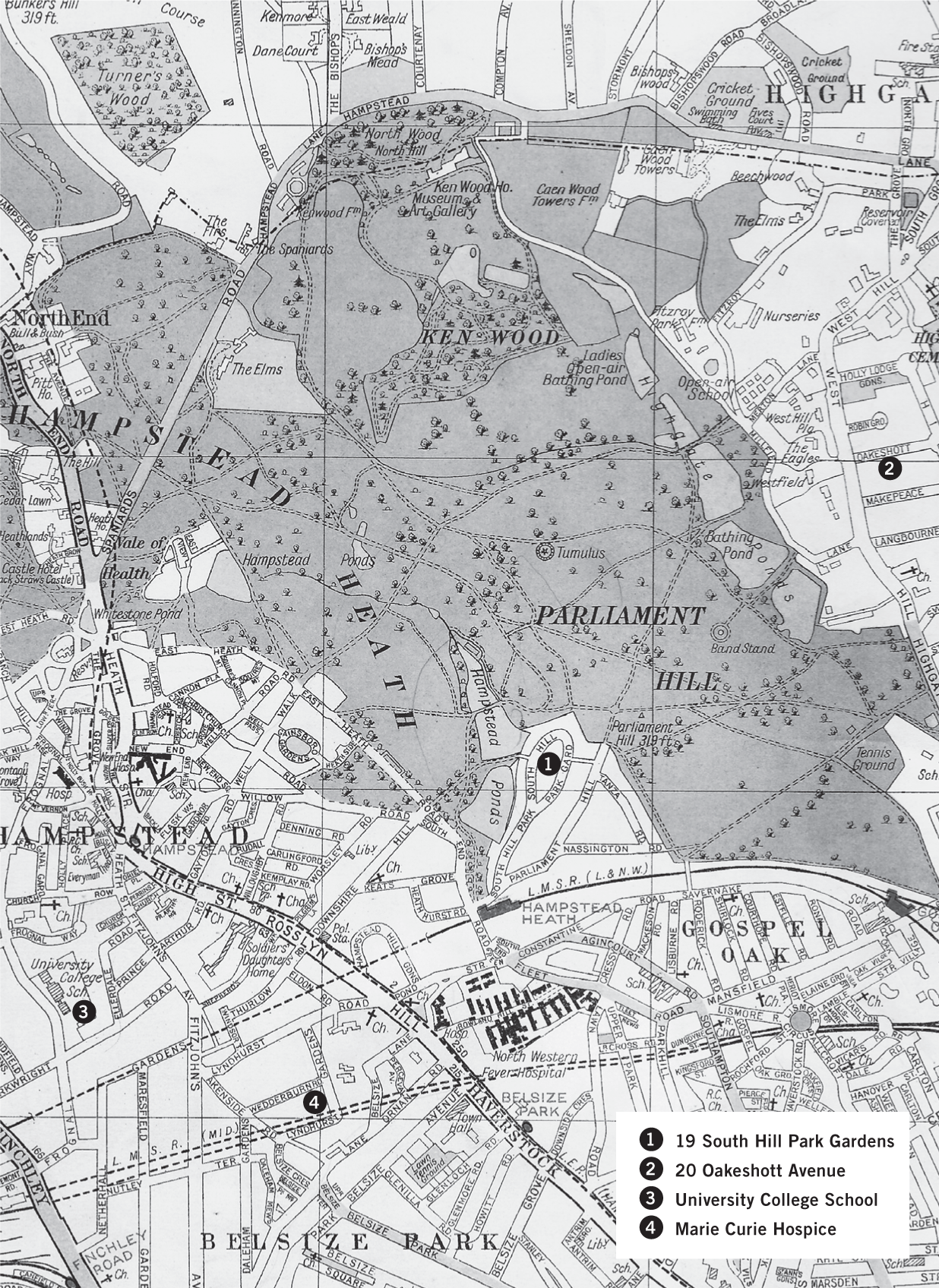

About fifty yards from where I would be standing there was a sign that marked a fork in the road: It had one arrow pointing to Highgate Village, the other to The North. As the cars sped past, in and out of town, there was something about that signperhaps it was the stark choice it offered, or maybe it was the midcentury fontthat got me thinking about the places Dad had called home. I realized that his eighty-plus years could be plottedstints in the army and college and business trips asideas a series of points around Hampstead Heath, the great rolling expanse of which unfolded below me. Unlike his parents, who had been uprooted from Russia and parted from their families and had suffered great hardship by the time they settled in London, his experience of home over the course of his life was pretty much contained within the circle of a days walk from where I was standing. Now it was ending only a couple of hundred yards from where it had begun, and I wondered whether the contentment I associated with himan acceptance of life, a kind of happiness, really, if it is not presumptuous to call it thatwas linked in some way to his enduring bond with the area, whatever it was that had drawn his parents not just to England but to this part of London in particular, and led them to make it their home and his.