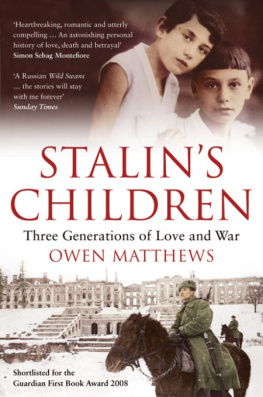

Praise forStalin's Children

"At a time when Russia is reasserting itself on the international stage, Stalin's Children should be required reading for anyone involved with economic, cultural or political relations with that country... All in all Mathews' contribution offers a poignant and insightful reading experience, leaving one with a keener sense of the unseen forces that drive present-day Russia."

-New York Post

"A moving book written with a tender yet unsentimental eye, a deeply intimate account that reveals through the lives of Matthews' own family how the Soviet experience shaped, and destroyed, millions of people."

-Douglas Smith,Seattle Times

"Few countries have been haunted more by a terrible past than Russia. In Stalin's Children Owen Matthews has written of the ghosts of his own family, with grandparents arrested in the Great Terror and his mother consigned to a Soviet orphanage when still an infant. His parents' love for each other, kept alight across the Iron Curtain, makes an extraordinary story. This wonderful memoir brings to life the human victims of a terrifyingly inhuman system."

-Antony Beevor,Sunday Telegraph

"[A] fascinating family memoir. Matthews relates this dramatic tale in understated but lovely prose... [an] extraordinary tale."

-Publishers Weekly

"A heartbreaking, romantic and utterly compelling piece of reportage that superbly tells the story of four generations of the author's own family across 20th Century Russia... Here is an astonishing personal history of love, death and betrayal in Russia by a half-Russian writer who really knows the texture of the Motherland."

-Simon Sebag Montefiore, author ofStalin: The Courtofthe Red TsarandYoung Stalin

"An epic account... brilliantly written."

-Guardian

"A superb chronicle of the 20th-century Soviet Union, seen through the eyes of his parents and grandparents: a Russian Wild Swans. Some of the stories will stay with me forever."

-Sunday Times(UK)

"Beautifully written and intensely moving."

-Daily Telegraph

"One of the most fascinating family memoirs of recent times."

-Literary Review

"Few books say so much about Russia then and now, and its effect on those it touches."

-Economist

"An extraordinary story... there are many moments of almost unbearable poignancy."

-Independent(UK)

"Gripping family history... This fascinating book is not a footnote to Soviet history: it is Soviet history, one of the millions of private tales of evil and astonishing endurance that make up the awful whole."

-Observer(UK)

"Remarkable... not only does Owen Matthews write with extraordinary vividness... but his technique is more that of a novelist than a journalist-and a master craftsman at that."

-Spectator

STALIN'S CHILDREN

Three Generations of Love, War, and Survival

OWEN MATTHEWS

Copyright 2008 by Owen Matthews

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Walker & Company, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10010.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

Published by Walker Publishing Company, Inc., New York

All papers used by Walker & Company are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA HAS BEEN APPLIED FOR

eISBN: 9780802777621

Visit Walker & Company's Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

First published by Walker & Company in 2008

This paperback edition published in 2009

I 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd., Edinburgh

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

The hand that signed the paper felled a city...

Doubled the globe of dead and halved a country.

Dylan Thomas

O n a shelf in a cellar in the former KGB headquarters in Chernigov, in the black earth country in the heart of the Ukraine, lies a thick file with a crumbling brown cardboard cover. It contains about three pounds of paper, the sheets carefully numbered and bound. Its subject is my mother's father, Bibikov, Boris Lvovich, whose name is entered on the cover in curiously elaborate, copperplate script. Just under his name is the printed title, 'Top Secret. People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs. Anti-Soviet Rightist-Trotskyite Organization in the Ukraine.'

The file records my grandfather's progress from life to death at the hands of Stalin's secret police as the summer of 1937 turned to autumn. I saw it in a dingy office in Kiev fifty-eight years after his death. The file sat heavily in my lap, eerily malignant, a swollen tumour of paper. It smelled of slightly acidic musk.

Most of the file's pages are flimsy official onion-skin forms, punched through in places by heavy typewriting. Interspersed are a few slips of thicker, raggy scrap paper. Towards the end are several sheets of plain writing paper covered in a thin, blotted handwriting, my grandfather's confessions to being an enemy of the people. The seventy-eighth document is a receipt confirming that he had read and understood the death sentence passed on him by a closed court in Kiev. The scribbled signature is his last recorded act on earth. The final document is a clumsily mimeographed slip, confirming that the sentence was carried out on the following day, 14 October 1937. The signature of his executioner is a casual squiggle. Since the careful bureaucrats who compiled the file neglected to record where he was buried, this stack of paper is the closest thing to Boris Bibikov's earthly remains.

In the attic of 7 Alderney Street, Pimlico, London, is a handsome steamer trunk, marked 'W.H.M. Matthews, St Antony's College, Oxford, AHrJIHA' in neat black painted letters. It contains a love story. Or perhaps it contains a love.

In the trunk are hundreds of my parents' love letters, carefully arranged by date in stacks, starting in July 1964, ending in October 1969. Many are on thin airmail paper, others on multiple sheets of neat white writing paper. Half - the letters of my mother, Lyudmila Bibikova, to my father - are covered in looping, cursive handwriting, even yet very feminine. Most of my father's letters to my mother are typed, because he liked to keep carbon copies of every one he sent, but each has a handwritten note at the bottom above his extravagant signature, or sometimes a charming little drawing. But those which he wrote by hand are closely written in tight, upright and very correct Cyrillic.

For the six years that my parents were separated by the fortunes of the Cold War, they wrote to each other every day, sometimes twice a day. His letters are from Nottingham, Oxford, London, Cologne, Berlin, Prague, Paris, Marrakech, Istanbul, New York. Hers are from Moscow, from Leningrad, from the family dacha at Vnukovo. The letters detail every act, every thought of my parents' daily lives. He sits in a lonely bedsit on a smoggy night in Nottingham, typing about his curry dinners and minor academic squabbles. She pines in her tiny room off Moscow's Arbat Street, writing about conversations with her friends, trips to the ballet, books she's reading.

Next page