For Scarlett, Titus and Jack love always.

The vastest things are those we may not learn.

Nor how to burn with love.

To those small things we are the masters of.

It all began on a rainy September morning in 1936.

Ive often pictured the high-ceilinged studio at the Westminster School of Art, transparent dots settling on the broad skylight above, like a Seurat. I see the students in their coloured smocks, red-mouthed women with sharp bobs, men in baggy trousers. I hear smoky laughter from the full-figured models and, up above, I see the dark skies of London spoiling for the start of autumn.

I see my father leaning over the clay, shaping it with his dexterous fingers. I see my mother walk nervously into the room. It was her first day at art school. She was seventeen. I know about this moment, how it was love at first sight.

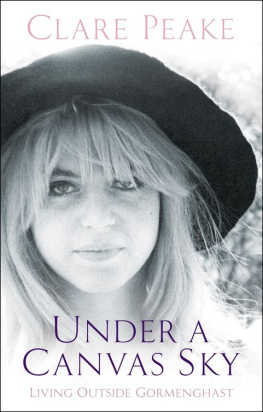

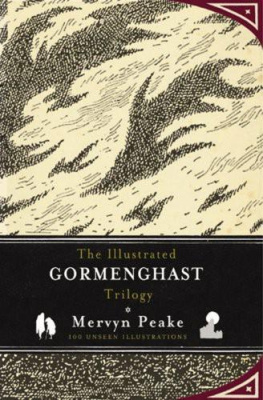

I havent seen my father for forty years and my mother for twenty-five, yet not a day goes by without my thinking of them. They pop in and out of my head with a comforting regularity as I look around me and wonder what they would make of the world. My mother, Maeve Gilmore, was a painter and my father, Mervyn Peake, a novelist, painter, poet and illustrator. If hed been just one of these things I sometimes think his life might have turned out differently. He has never been easy to place. To some he is the author of the Gormenghast trilogy, to others the illustrator of classics they loved as a child. Some know him as a poet and many dont know him at all. I knew him as a father, and as a father his talents were as great as any line drawing he ever sketched or sentence he ever wrote.

The first few years of my life were wonderfully happy. It seemed I inhabited an enchanted playground, where all the wonders of the world were there, before my eyes; a place where creativity, love and laughter were all you needed for a contented and satisfied soul. Our life abruptly altered when my father became ill. Beginning with a nervous breakdown, it ended with Parkinsons disease, the final diagnosis taking years to discover. It changed him from a cheerful, easy-going man into a frightened stranger, locked into his own private nightmare a place too far away for me to reach.

In my small world, as the youngest child and only daughter, I was protected from too much pain by a fierce respect for childhood nothing was allowed to ruin that crucial and fleeting moment. Life for Mervyn and Maeve was much harder than they ever let on and deep down I knew this but, because outwardly they appeared light-hearted and optimistic, I allowed myself to be fooled. Twelve of my fathers fifty-seven years were spent in and out of mental institutions and during that time I lived in a haze of confusion, believing that nervous breakdowns and mental hospitals were just a part of life.

Since this book is primarily about my parents I should declare at once that I adored them. I didnt adore them because they were my parents, but because they were charming, loving, generous-hearted people, and an absolute joy to be around. With a surfeit of creativity surrounding me wherever I turned, little money and a healthy disregard for convention, an outsider might quite rightly describe our household as bohemian. I saw it only as a munificent and passionate sanctuary, where ideas were everything and love was the key.

The sprawling Victorian house I grew up in is engraved on my mind forever as the scene of more happiness and more despair than anywhere I lived before or have lived since. When my paternal grandparents died, they left their house to my father and, in 1953, when I was four, we moved from Chelsea to the Surrey suburbs. For the next seven years it signified a period in time that was neatly sliced in two, the first half idyllic, the second bewildering and sad.

In 1960 we moved back to Chelsea and life changed again, and for the better. London in the 1960s was a place with a romance all of its own. Optimism clung to the air, a sense of daring made anything seem possible, as if everything were being experienced for the first time. The films, art, theatre, music and fashion were so exciting and inventive you felt yourself to be a participant in a pageant of kaleidoscopic colour. For a time, Mervyn was central to the spirit of this era. While he was languishing in bleak hospitals all over the country, Penguin Books republished the Gormenghast trilogy and, with a fervour, his books were read, dissected and loved by a mass of people in a way hed never know, never have believed was possible. The books became essential reading, part of the very fabric of a generations combined memory, and of this I am incredibly proud.

During this difficult time my mother, with a stubborn refusal to give in to self-pity or gloom, created an atmosphere at home that was thrillingly glamorous and alive. Her parties were legendary occasions. Writers, painters, poets and publishers would talk, drink and dance the night away until the early hours, and I cant remember my teenage years without conjuring up an image of our house echoing with the sounds of people having fun.

I have spent my whole life wanting to protect my father. I didnt know that until I began to write this book. Introduced to strangers with my pedigree thrown in as an icebreaker, I long to run away. The complexities of the opening line Mervyn Peakes daughter create a minefield of awkwardness and embarrassment. Will they stare at me blankly, will they say something clever or will they be nice? I never know. The reason I wanted to protect him, and still do, is because his illness was so awful and pervasive that, as a child, I saw him unable to protect himself. He shrank before my eyes and I felt it my job to straighten him up, to shield him from those who might want to hurt him, to protect this towering man my hero from the world.

I dont exaggerate when I say that Maeve and Mervyns life was one of extremes, the greatest of happiness and the lowest of despair, but with a love so deep and a friendship so enduring it allowed them to believe theyd been lucky. They retained a lack of world-weariness and cynicism that to a child was magical. It was not borne out of naivety but of something else a belief in people and a genuine love of life.

I have tried to recapture the feeling of a time that is drifting farther and farther away, but for now seems as close as ever. Despite the sadness that coloured our lives, I can only look back with fondness at a time that, unrealistic as it may sound, was glorious. I knew then, as I know now, that what I witnessed was unique.

B ehind the compound walls stood six identical grey stone houses, built for the missionaries and their families. Beyond lay China. In one of these double-shuttered, three-storeyed houses, the fourth one along, nearest the tennis court, Mervyn sat drawing at the dining-room table. When I visualise my father as a child, I see him at this table, lost in concentration, an endlessly replenished supply of paper, pencils and crayons spread in front of him, as he draws anything, real and imagined, that he sees. From the moment he could clasp a pencil his parents recognised their sons precocious talent, and encouraged him in his passionate love of drawing. I know that the constant interruptions for meals irritated Mervyn. The obligatory tidying away of pencils and paper to make way for another round of food was to him a hated irrelevance. Im told he had to be dragged from the table to go to bed. I see him glancing out of the dining-room window, his senses bombarded by the sights and sounds of Tientsin, northern China, where he lived until he was twelve.

It was a happy childhood, a lively, affectionate home with his Congregationalist medical missionary parents, Doc and Bessie, and elder brother Lonnie, a conventional, middle-class upbringing in the most unconventional of settings, and the very English wordplay, puns and imagery Doc used in his everyday speech were to influence my father for the rest of his life. Mervyn was fascinated by his fathers work. Every day on his way to school by mule and, later, bicycle he passed hordes of injured people queuing for Docs surgery, and the cure that would miraculously heal them. Doc performed over a thousand operations a year with Bessie, a nurse, and local assistants by his side, speaking Mandarin to his local assistants, training them in all aspects of medicine. Sometimes Mervyn hid in the viewers gallery, surreptitiously watching his father performing his operations, once fainting as he watched Doc sawing through the leg of a young Chinaman, the severed limb being carried off on a tray of sawdust.