Mudlark

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

HarperCollinsPublishers

Macken House, 39/40 Mayor Street Upper

Dublin 1, D01 C9W8, Ireland

First published by Mudlark 2022

FIRST EDITION

Owen Matthews 2022

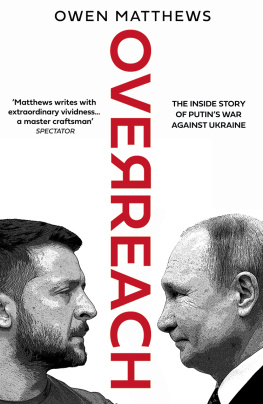

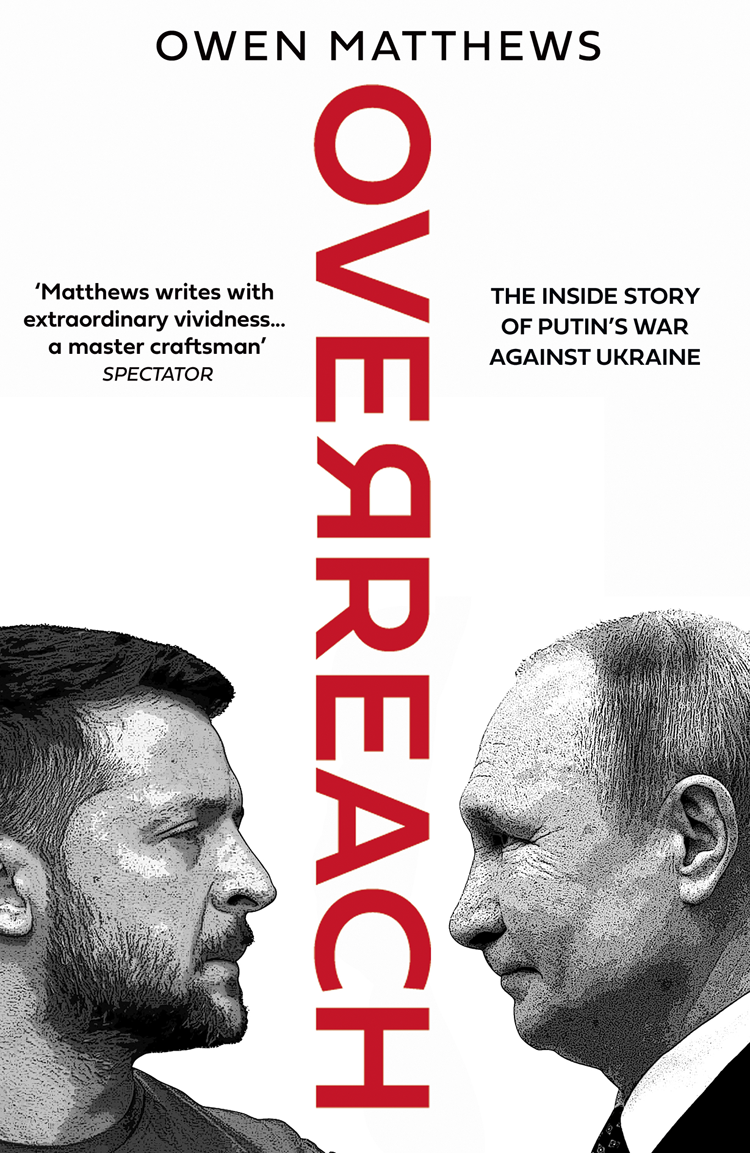

Cover design by Claire Ward HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2022

Jacket photographs front: Reuters/Alamy Stock Photo (President Zelensky) and Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images (President Putin)

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Owen Matthews asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008562748

Ebook Edition November 2022 ISBN: 9780008562755

Version: 2022-10-10

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

- Change of font size and line height

- Change of background and font colours

- Change of font

- Change justification

- Text to speech

- Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008562748

For Ksenia, Nikita and Teddy

For with pomp to meet him came,

Clothed in arms like blood and flame,

The hired murderers, who did sing

Thou art God, and Law, and King.

We have waited, weak and lone

For thy coming, Mighty One!

Our purses are empty, our swords are cold,

Give us glory, blood, and gold.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Mask of Anarchy, 1819

What this country needs is a short, victorious war.

Prime Minister Vyacheslav von Plehve to Tsar Nicholas II, 1904

Everyone must understand: mobilisation is ahead and a global war for survival, for the destruction of all our enemies. War is our national ideology. And our only task, our leaders only task, is to explain to and convince all the Russian people that this our heroic future.

Russian writer and volunteer Donbas fighter Zakhar Prilepin, April 2014

Youd be happy to meet. My old friend Zhenias tone on the phone was flat and wary. It was 28 March 2022. The war in Ukraine had been under way for a month. You want to meet just for the sake of happiness or are you going to try to tell me why Im wrong?

Maybe you can tell me why Im wrong? We can do that too. Im in Moscow.

There was a silence on the line.

Maybe some other time, he eventually replied. Its not a good idea for me to be seen with you right now.

Once, Zhenia had been a rebel. At various stages of his career hed worked as a labourer and a security guard, and served as an officer in the paramilitary OMON police and fought in Chechnya. He had edited the Nizhny Novgorod edition of the opposition Novaya Gazeta and had been a leading member of the revolutionary National Bolshevik Party. But by the time I met him at a literary festival in Saint-Malo, France, Zhenia had adopted a new pen-name Zakhar Prilepin and had become one of Russias greatest and most controversial novelists. Zhenia was shaven-headed, physically strong and had a generally threatening mien that had got him into a spot of bother with Saint-Malos CRS riot police. I helped him out of it. It was a bonding experience.

Zhenia Zakhar Prilepin was smart, well-read, unafraid. He was also passionate about his beliefs which included a radical faith in the greatness of his country and a withering contempt for the venality of its current leadership. At a writers forum in the Kremlin in 2007 hed sat across from Vladimir Putin and fearlessly taken the president to task for corruption and thievery. After the February 2014 annexation of Crimea, the Kremlins ideology had turned on its axis, and Putin and Zakhar found themselves in unexpected agreement: it was time for Russia to take up arms against her enemies. Soon after, Zakhar travelled to the rebel republics of Donbas in eastern Ukraine and became the deputy commander of a rebel battalion. In 2020, like his hero the radical writer and National Bolshevik Party founder Eduard Limonov, Zakhar founded a political party of his own. Its vision was of a manly, belligerent Russia whose destiny it was to purge the world of decadence through war.

Zakhars views may have been poisonous and insane and were undoubtedly dangerous. But they were sincerely held. And unlike many armchair patriots in the Russian elite who spent most of their time plundering the country they professed to love, Prilepin actually risked his skin for his beliefs. He was once my friend. Now, I suppose, he has become a kind of honest enemy.

I start this story with Zakhar for two reasons. One is that I am interested in what he will do next. Currently, the Kremlin is riding the tiger of Orthodox-fuelled ultra-nationalism that until relatively recently had lurked on the lunatic fringes of Russian politics. What will happen if Putin falters, either through military failure in the field or by losing his grip on the Russian elite or security services? If that were to occur, Zakhars vision of his country as a kind of new Sparta, implacable, militant and fired with holy righteousness, could be a terrifying glimpse into one of Russias possible futures.

The second reason I mention Zakhar is his refusal of my invitation to meet. I never found out his reasons. Perhaps he was nervous of being caught talking to someone who could be presented as a Western spy. Perhaps he thought I had become a Western spy. Perhaps he assumed that I was being tailed by the Federal Security Service, or FSB. Perhaps he thought he was. Perhaps he was afraid of hearing a different version of events from me that would shake his faith in his belief that Russian Orthodox warriors were battling Ukrainian Nazis (admittedly unlikely).

Whatever his reasons, Zakhar had clearly caught a dose of the pervasive paranoia of the times. It was a paranoia shared by the majority of my Moscow friends, colleagues and contacts. In the days following the beginning of the war it covered the city as quickly and obtrusively as the peat-fire smog that blankets Russias capital every summer. And like smoke, paranoias lingering smell was pervasive and impossible to avoid.

I have spent, on and off, 27 years reporting in Russia first as a metro and features reporter for The Moscow Times and then as a correspondent and Moscow Bureau Chief for Newsweek magazine. In over a quarter of a century a total of perhaps half a dozen people refused to speak to me because I was a foreigner, or because they feared repercussions from the authorities.

That changed dramatically after the beginning of Russias invasion of Ukraine or, more specifically, after the State Duma passed a law in early March making the dissemination of false news about the Russian Military punishable with up to 15 years in prison. Soon afterwards the Duma also redefined an existing law on foreign agents to include not just Russian individuals and organisations who actually received funding from abroad but also those who had come under foreign influence. Weekly lists of new foreign agents were published and soon came to include almost every non-Kremlin-aligned journalist, broadcaster, blogger and analyst.