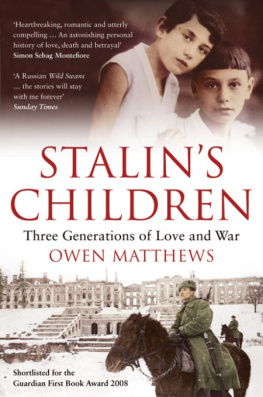

Owen Matthews

STALINS CHILDREN

Three Generations of Love and War

The hand that signed the paper felled a city

Doubled the globe of dead and halved a country.

Dylan Thomas

On a shelf in a cellar in the former KGB headquarters in Chernigov, in the black earth country in the heart of the Ukraine, lies a thick file with a crumbling brown cardboard cover. It contains about three pounds of paper, the sheets carefully numbered and bound. Its subject is my mothers father, Bibikov, Boris Lvovich, whose name is entered on the cover in curiously elaborate, copperplate script. Just under his name is the printed title, Top Secret. Peoples Commissariat of Internal Affairs. Anti-Soviet Rightist-Trotskyite Organization in the Ukraine.

The file records my grandfathers progress from life to death at the hands of Stalins secret police as the summer of 1937 turned to autumn. I saw it in a dingy office in Kiev fifty-eight years after his death. The file sat heavily in my lap, eerily malignant, a swollen tumour of paper. It smelled of slightly acidic musk.

Most of the files pages are flimsy official onion-skin forms, punched through in places by heavy typewriting. Interspersed are a few slips of thicker, raggy scrap paper. Towards the end are several sheets of plain writing paper covered in a thin, blotted handwriting, my grandfathers confessions to being an enemy of the people. The seventy-eighth document is a receipt confirming that he had read and understood the death sentence passed on him by a closed court in Kiev. The scribbled signature is his last recorded act on earth. The final document is a clumsily mimeographed slip, confirming that the sentence was carried out on the following day, 14 October 1937. The signature of his executioner is a casual squiggle. Since the careful bureaucrats who compiled the file neglected to record where he was buried, this stack of paper is the closest thing to Boris Bibikovs earthly remains.

In the attic of 7 Alderney Street, Pimlico, London, is a handsome steamer trunk, marked W.H.M. Matthews, St Antonys College, Oxford, in neat black painted letters. It contains a love story. Or perhaps it contains a love.

In the trunk are hundreds of my parents love letters, carefully arranged by date in stacks, starting in July 1964, ending in October 1969. Many are on thin airmail paper, others on multiple sheets of neat white writing paper. Half the letters of my mother, Lyudmila Bibikova, to my father are covered in looping, cursive handwriting, even yet very feminine. Most of my fathers letters to my mother are typed, because he liked to keep carbon copies of every one he sent, but each has a handwritten note at the bottom above his extravagant signature, or sometimes a charming little drawing. But those which he wrote by hand are closely written in tight, upright and very correct Cyrillic.

For the six years that my parents were separated by the fortunes of the Cold War, they wrote to each other every day, sometimes twice a day. His letters are from Nottingham, Oxford, London, Cologne, Berlin, Prague, Paris, Marrakech, Istanbul, New York. Hers are from Moscow, from Leningrad, from the family dacha at Vnukovo. The letters detail every act, every thought of my parents daily lives. He sits in a lonely bedsit on a smoggy night in Nottingham, typing about his curry dinners and minor academic squabbles. She pines in her tiny room off Moscows Arbat Street, writing about conversations with her friends, trips to the ballet, books shes reading.

At some moments their epistolary conversation is so intimate that reading the letters feels like a violation. At others the pain of separation is so intense that the paper seems to tremble with it. They talk of tiny incidents from the few months they spent together in Moscow, in the winter and spring of 1964, their talks and walks. They gossip about mutual friends and meals and films. But above all the letters are charged with loss, and loneliness, and with a love so great, my mother wrote, that it can move mountains and turn the world on its axis. And though the letters are full of pain, I think that they also describe the happiest period of my parents lives.

As I leaf through the letters now, sitting on the floor of the attic which was my childhood room, where I slept for eighteen years not a yard from where the letters lay in their locked trunk, in the box room under the eaves of the house, and where I listened to my parents raised voices drifting up the stairs, it occurs to me that here is where their love is. Every letter is a piece of our soul, they mustnt get lost, my mother wrote during their first agonizing months. Your letters bring me little pieces of you, of your life, your breath, your beating heart. And so they spilled their souls out on to paper reams of paper, impregnated with pain, desire and love, chains of paper, relays of it, rumbling through the night on mail trains across Europe almost without interruption for six years. As our letters travel they take on a magical quality in that lies their strength, wrote Mila. Every line is the blood of my heart, and there is no limit to how much I can pour out. But by the time my parents met again they found there was barely enough love left over. It had all been turned to ink and written over a thousand sheets of paper, which now lie carefully folded in a trunk in the attic of a terraced house in London.

* * *

We believe we think with our rational minds, but in reality we think with our blood. In Moscow I found blood all around me. I spent much of my early adult life in Russia, and during those years I found myself, time and again, tripping over the roots of experience which grew into recognizable elements of my parents character. Echoes of my parents lives kept cropping up in mine like ghosts, things which remained unchanged in the rhythms of the city which I had believed was so full of the new and the now. The damp-wool smell of the Metro in winter. Rainy nights on the backstreets off the Arbat when the eerie bulk of the Foreign Ministry glows like a fog-bound liner. The lights of a Siberian city like an island in a sea of forest seen from the window of a tiny, bouncing plane. The smell of the sea-wind at Tallinn docks. And, towards the end of my time in Moscow, the sudden, piercing realization that all my life, I had loved precisely the woman who was sitting by my side at a table among friends in a warm fug of cigarette smoke and conversation in the kitchen of an apartment near the Arbat.

Yet the Russia I lived in was a very different place from the one my parents had known. Their Russia was a rigidly controlled society where unorthodox thought was a crime, where everyone knew their neighbours business and where the collective imposed a powerful moral terror on any member who dared defy convention. My Russia was a society adrift. During the seventy years of Soviet rule, Russians had lost much of their culture, their religion, their God; and many of them also lost their minds. But at least the Soviet state had compensated by filling the ideological vacuum with its own bold myths and strict codes. It fed people, taught and clothed them, ordered their lives from cradle to grave and, most importantly, thought for them. Communists men like my grandfather had tried to create a new kind of man, emptying the people of their old beliefs and refilling them with civic duty, patriotism and docility. But when Communist ideology was stripped away, so its quaint fifties morality also disappeared into the black hole of discarded mythologies. People put their faith in television healers, Japanese apocalyptic cults, even in the jealous old God of Orthodoxy. But more profound than any of Russias other, new-found faiths, was an absolute, bottomless nihilism. Suddenly there were no rules, no holds barred, and everything went for those bold and ruthless enough to go out and grab as much as they could.