STALINS NOSE

Across the Face of Europe

Rory MacLean

Preface by Colin Thubron

A minor masterpiece of comic surrealism.

The Times

The most extraordinary debut in travel writing since In Patagonia. A dark, sardonic and brilliant book which grows in stature with every page.

William Dalrymple

a surreal, zanily nihilistic comedy

The New York Times

Crazy, charming, a delight

John le Carr

As an allegory it is powerful and frequently moving. As a tale it is tremendous fun. It is also a thing of beauty

Jan Morris

There is pathos and adventure in spades... Stalins Nose is an essential companion for anyone travelling to a part of the world still recovering from the horrors of the giant confidence trick that was communism.

Justin Marozzi, Financial Times

It is a painful book of bitter old ages, or lives which have had their meanings repeatedly declared void. It is very hard and very good.

Guardian

A Gogolesque tour in a Trabant: eccentric, amusing and chilling.

The Economist

The wittiest, most surreal travel writing of recent years.

Frank Delaney

The best book Ive read for a long time.

John Wells

Copyright 1992, 2008, 2013 Rory MacLean

First published by Harper Collins Publishers in 1992

www.rorymaclean.com

Cover image: Painting on Berlin Wall John Slater/CORBIS

ISBN: 978-1-78301-166-7

The moral right of Rory MacLean to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

eBook conversion by eBookPartnership.com

Contents

Preface

WITH THE PUBLICATION of Stalins Nose in 1992, a new and distinctive voice sounded in the field of travel writing. By turns zany, lyrical, troubled, fantastical, Rory MacLeans first book crashed through the norms of the genre to create a surreal masterpiece. And for this burlesque tour de force the author travelled a region not of comfort but of bizarre human tragedy, as if reminding the reader that laughter arises less from happiness than from the detonations of the unexpected.

Stalins Nose poses, too, a vital question of form: how much of it is true? Is it permissible for a travel writer to invent? And if so, how much, and in what way? Most readers take the reporters experience on trust for if events have been invented, they lose their power as well as their truth. Somewhere in the book, it is felt, any fictionalising must be acknowledged.

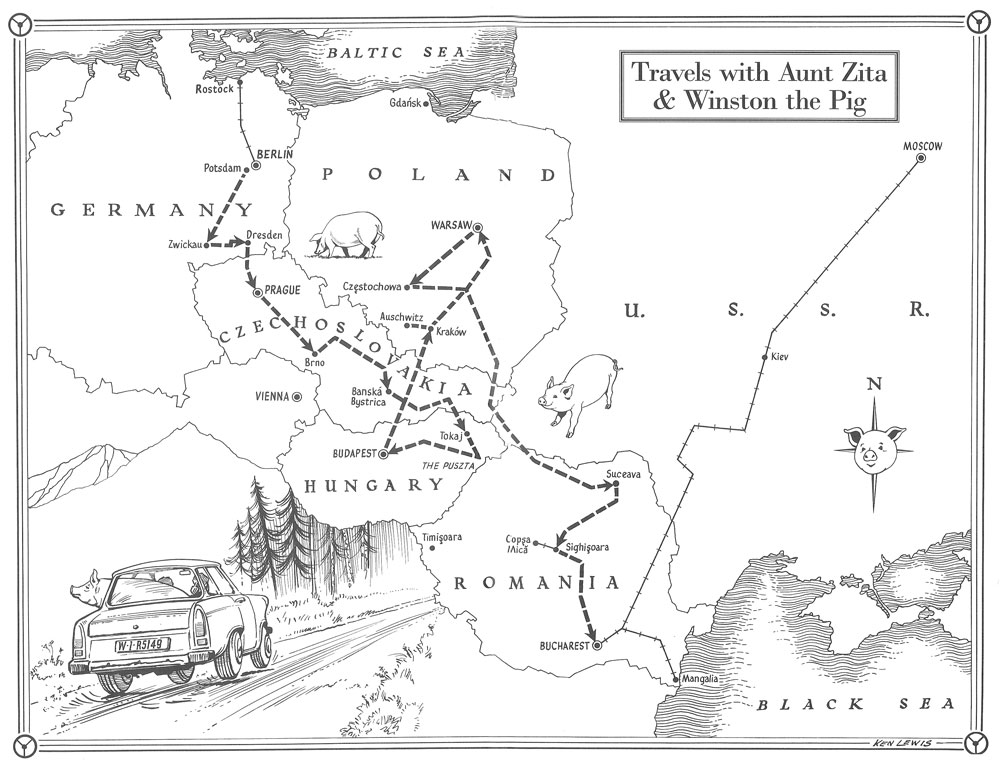

But MacLean overrides the borders between fact and fiction to create a literary species almost his own. A journey in a decrepit Trabant, in the company of a theatrically eccentric aunt, a Tamworth pig and (in Czechoslovakia) the coffin of a long-dead pilot strapped to the roof cannot be the stuff of literal reality. The reader is invited, instead, into a stark, hyper-real world. Stalins Nose is not so much a travelogue as the intense distillation of a journey, and its crazy progress becomes an allegory of the tortured countries through which the travellers go. For this is the Eastern Europe of 1989-90, emerging from its Communist nightmare into a world of smoke and mirrors, confronted by its own delusions and half-truths, hypocrisies and self-blindings. Nazism and Stalinism have become interchangeable myths, bodied out in personal lives. Comedy mirrors tragedy. Moral confusion reigns.

Above all, this drama is acted out through the books central character, the authors zestful, eccentric, belligerent aunt Zita a faded beauty with memorably misaligned ears who clings to the shreds of her Communism. Piece by piece her world is revealed as a moral shambles. As she and the author travel from Berlin to Prague, Brno to Budapest, they are greeted by cousins who were secret policemen, state informers, only occasionally heroes. Her brother Oto, whom Zita had adored, turns out to have been an SS officer at Auschwitz. Her husband, whose death is announced in the books opening sentence (the Tamworth pig falls on his head) is revealed in ever blacker colours. Yet the authors affection for the mercurially human Zita shines through all her crankiness. Inhuman acts horrify him; but human beings, he seems to say, are too fragile, often too ludicrous, for the withholding of compassion.

For a while the travellers are accompanied by Zitas sister Vera, who had fought against the Nazis in the Slovak resistance, been betrayed under Communism and fled to the West. She is both Zitas opposite and mirror image, and they battle derisively against one another. In Bansk Bystrica, listening to an old phonograph belonging to a cousin, they hear the voice of their long-dead brother.

It doesnt sound anything like him. Zita turned to Vera. Whats he singing? A girls voice accompanied the song. And whos the warbler?

Its you, youre singing the SS song together, she replied. Vera laughed the sort of laugh lovers make when confessing to infidelity. A Communist as a fianc and a fascist for a brother, I dont know how you resolved that one.

And bloody you as a sister, that was the bugger in the wood-pile. Oto was no fascist. He was an ordinary soldier and handsome to boot. But it wasnt true.

Ordinary soldiers didnt volunteer for the SS. But they did.

Dont be ridiculous. Zitas voice was shrill. Oto had no choice. She held her throat as if to strangle herself.

The ancestry of this remarkable book is not to be found in British travel-writing. Rory MacLean is a Canadian, who started his working life as a film-maker, and he has said that it is film its scenic structuring and deployment of dialogue for driving a plot forward which influenced him most potently. While still in his early twenties, a three-year stint as a film-maker in Berlin and a voracious reading of Eastern European literature (Bulgakov, Kundera) ignited an enduring fascination with Cold War Europe.

Early in Stalins Nose he expresses his need to understand how generations of his (partly fictionalised) aunts and uncles had become, in effect, murderers. My forebears had killed not as individuals, as individuals they were honourable, but as groups the Cheka, the Iron Guard, the Gestapo, the KGB to which they had surrendered their individuality I wanted to try to comprehend the discrepancy between the morality of a man and of men. To know how we can love someone we fear. How do people grow blind to their human experience, clouding it with dogma, worshipping distant tyrants? We loved them because they freed us from the burden of self; but we feared them because with our surrender of personality they controlled us.

But the answers to MacLeans questions, in the end, lie deep in the texture of Stalins Nose itself, in its evocation of lives surrendered to phantoms, lives described with a unique mixture of comic bravado, underlying horror and a pervasive tenderness.

Colin Thubron, London

GERMANY

If Pigs Could Fly

Winston the pig fell into Zitas life when he dropped onto my uncles head and killed him dead. The news reached me in Rostock, drab, damp, and winter gray, where my trip had begun. I had planned to travel from the Baltic to the Black Sea, across the continents waist, along the line of the old Iron Curtain, but a telephone call changed everything.