FITZROY MACLEAN

A PERSON

FROM ENGLAND

AND OTHER TRAVELLERS

Sweet to ride forth at evening from the wells,

When shadows pass gigantic on the sand,

And softly through the silence beat the bells

Along the Golden Road to Samarkand.

FLECKER

This electronic edition published in 2011 by Bloomsbury Reader

Bloomsbury Reader is a division of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

Copyright Sir Fitzroy Maclean, BT 1958

The moral right of author has been asserted

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise

make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means

(including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying,

printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the

publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication

may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages

ISBN: 9781448205240

eISBN: 9781448204809

Visit www.bloomsburyreader.com to find out more about our authors and their books

You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can sign up for

newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers

CONTENTS

FOR

CHARLES AND JAMES

WHO HAVE STILL

TO START

THEIR TRAVELS

ROUND about the year 1890, the hero of an early novel by John Buchan finally redeemed the failures of an otherwise unsatisfactory life by repulsing single-handed a sizeable Russian army which he found, while on a shooting expedition, in the act of invading India. He did it with a sporting rifle and with a conveniently placed boulder which at the critical moment he toppled down on the intruders.

At about the same time, Kiplings Man Who Was crawled out of Central Asia and into the mess of his old regiment, the White Hussars, who happened to be stationed somewhere near the Khyber Pass. He had been so roughly handled over the past thirty years by some Russians, whose Colonel he had insulted, and more recently by the outposts of the White Hussars, who had unfortunately mistaken him for an Afghan, that he died three days later. But not before the circumstances of his brief reappearance had revealed in his true colours the apparently charming Cossack officer who happened to be visiting the White Hussars at the time and had also served to remind that dashing regiment that a couple of hundred miles to the north of the Khyber was an enemy worthier of their steel than the unruly tribesmen who periodically sniped at them from the neighbouring hilltops.

And then, of course, there was Kim, whose real name was Kimball OHara, and who at the age of seventeen managed, with his friend the Guru, completely to upset the plans of the Tsars Intelligence Service.

But it was not only in the realms of romantic fiction that such characters had their being. They really existed. Even the invading Russian army was a reality, though the boulder that finally checked its progress was a diplomatic one.

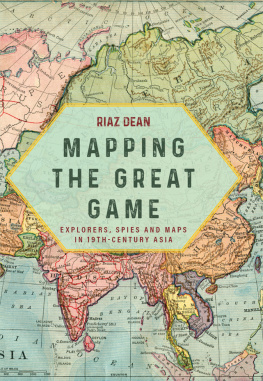

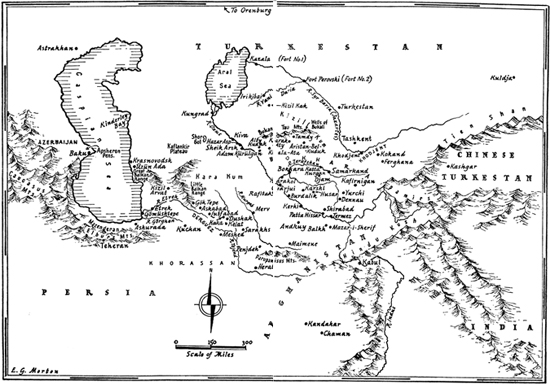

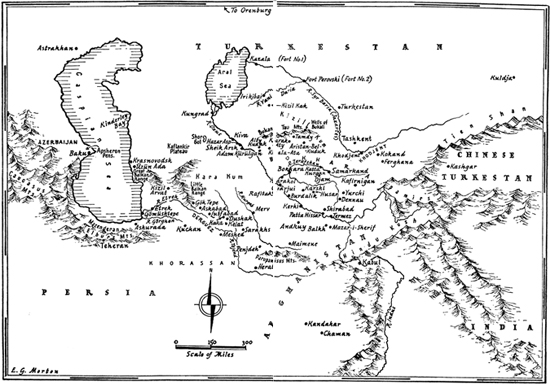

For the greater part of the nineteenth century, and after it, up and down the length and breadth of Central Asia, from the Caspian to the Karakoram and from the Khyber Pass to the confines of Siberia, throughout the whole of the vast, but rapidly narrowing Tom Tiddlers Ground that separated their respective Empires, Englishmen and Russians, and men of other races and nationalities too, played what they and their contemporaries called The Great Game. Played it from various motives and with varying degrees of success. Played it, on the whole, with courage and resourcefulness, with dash and initiative, and with no great attention to any particular set of rules.

For a space, the attention of the world was focused on Central Asia. Men risked their lives to get there. Not many succeeded and not all of them returned to tell the tale. But, between them, both figuratively and literally, they put Central Asia on the map.

And then a strange thing happened. As the spheres of influence crystallized and the tension between Great Britain and Russia subsided, people forgot about Turkestan. Today, it is by no means everyone who knows where to look for Merv or Bokhara or is even sure to what country they now belong. And the men who for one reason or another once risked their lives to reach them have for the most part been forgotten too.

Because this seemed to me a pity, I conceived the idea of writing a book about some of them. The result is not a serious work of scholarship. Though it contains, it is true, the results of a certain amount of original research, much of what I have written has already been told. Much was known, seventy or eighty years ago, to every schoolboy. But I have enjoyed writing it and for my part I shall be content if I help to revive memories of some men who deserve to be remembered and at the same time manage to give my readers some idea of the regions to which they travelled, of the times in which they lived and of the restless, adventurous spirit that drove them on.

How extraordinary! I have two hundred thousand Persian slaves here; nobody cares for them; and on account of two Englishmen, a person comes from England, and single-handed demands their release.

EMIR NASRULLAH OF BOKHARA

IF, as you are approaching Richmond Bridge from London, you turn aside from George Street and make your way through one of the narrow passages which lead off it to the right, you will find yourself on Richmond Green, a broad expanse of grass, fringed with trees and surrounded by handsome red-brick Georgian houses.

Anyone passing that way after breakfast on July 7th, 1843, might have seen the door of one of these houses open and a grubby, undersized, rather wild-looking man of about fifty emerge, garbed as a curate of the Church of England. The rain which had fallen earlier that morning had cleared away and, after glancing about him with an air of studied unconcern (for he did not wish his wife to think that anything unusual was afoot), the curate proceeded to stroll up and down the green, as though taking the air. But he did not remain alone for long. Before many minutes had passed, there arrived on the scene a gentleman of military bearing and appearance, looking about as though in search of somebody or something. The curate at once accosted him, and the two, having shaken hands, were soon engaged in animated conversation.

From their manner, an observer might have deduced that the curate and his companion were discussing some project or plan. This deduction would have been correct. But the project was no ordinary project. Nor could the curate by any stretch of the imagination have possibly been described as an ordinary curate.

By experience and outlook, no less than by origin and upbringing, the Reverend Joseph Wolff, D.D., lately Curate of High Hoyland in Yorkshire, was as different as he well could be from the mild young clerics who had already begun to provide a target for the wit of contributors to the daring new periodical which tor the past two years had been appearing under the title of Punch or The London Charivari. His appearance and manner, too, were distinctly unusual. He is, wrote a female contemporary, a strange and most curious-looking man; in stature short and thin, and his weak frame appears very unfit to bear the trials and hardships to which he has been, and will be, exposed in his travels. His face is very flat, deeply marked with smallpox; his complexion that of dough, and his hair flaxen. His grey eyes roll and start, and fix themselves, at times most fearfully; they have a cast in them, which renders their expression still wilder His pronunciation of English is very remarkable; at times it is difficult to understand him: however, his foreign accent gives originality to his lectures, aided occasionally by vehement gesticulation. His voice is deep and impressive; at times, having given way to great and deep enthusiasm, and having arrested the attention of his hearers, he sinks at once down into some commonplace remark, his voice becomes a most curious treble, the effect of which is so startling, one can scarcely refrain from laughter.

Next page