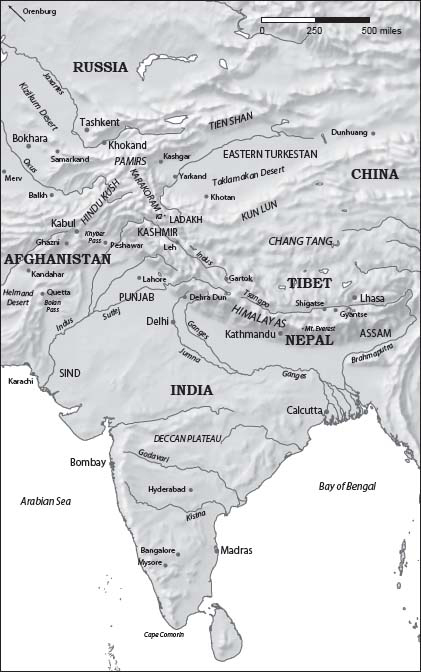

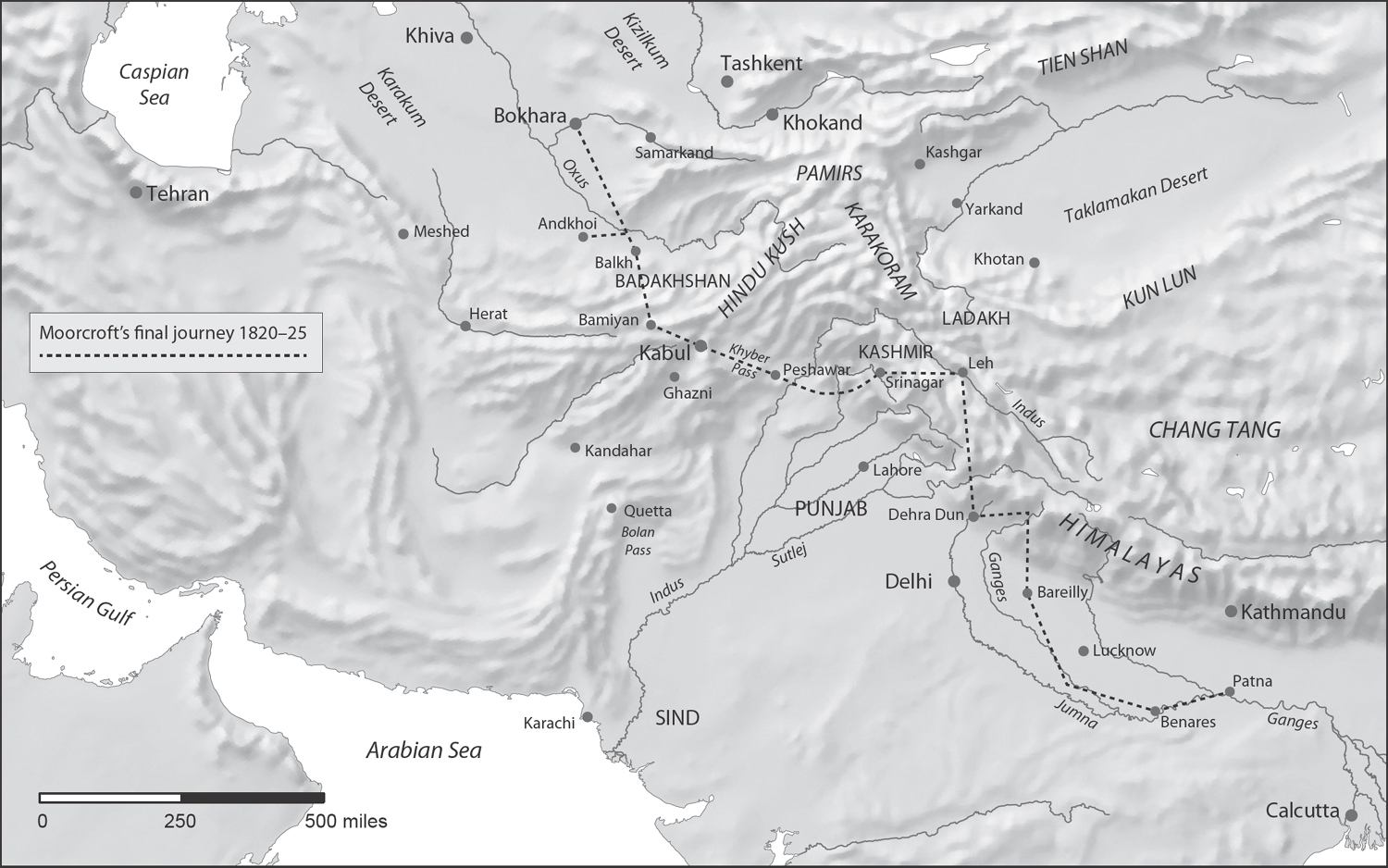

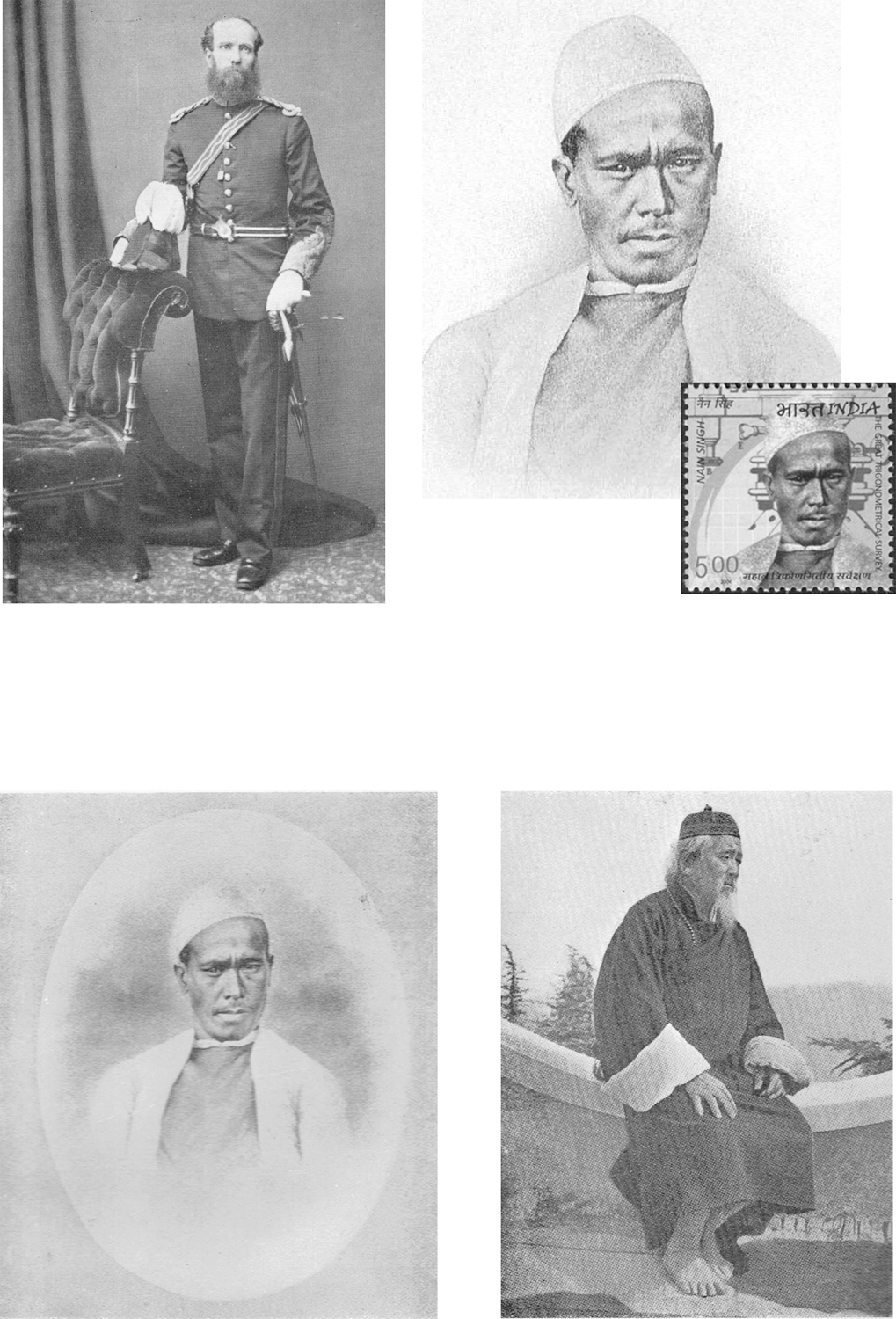

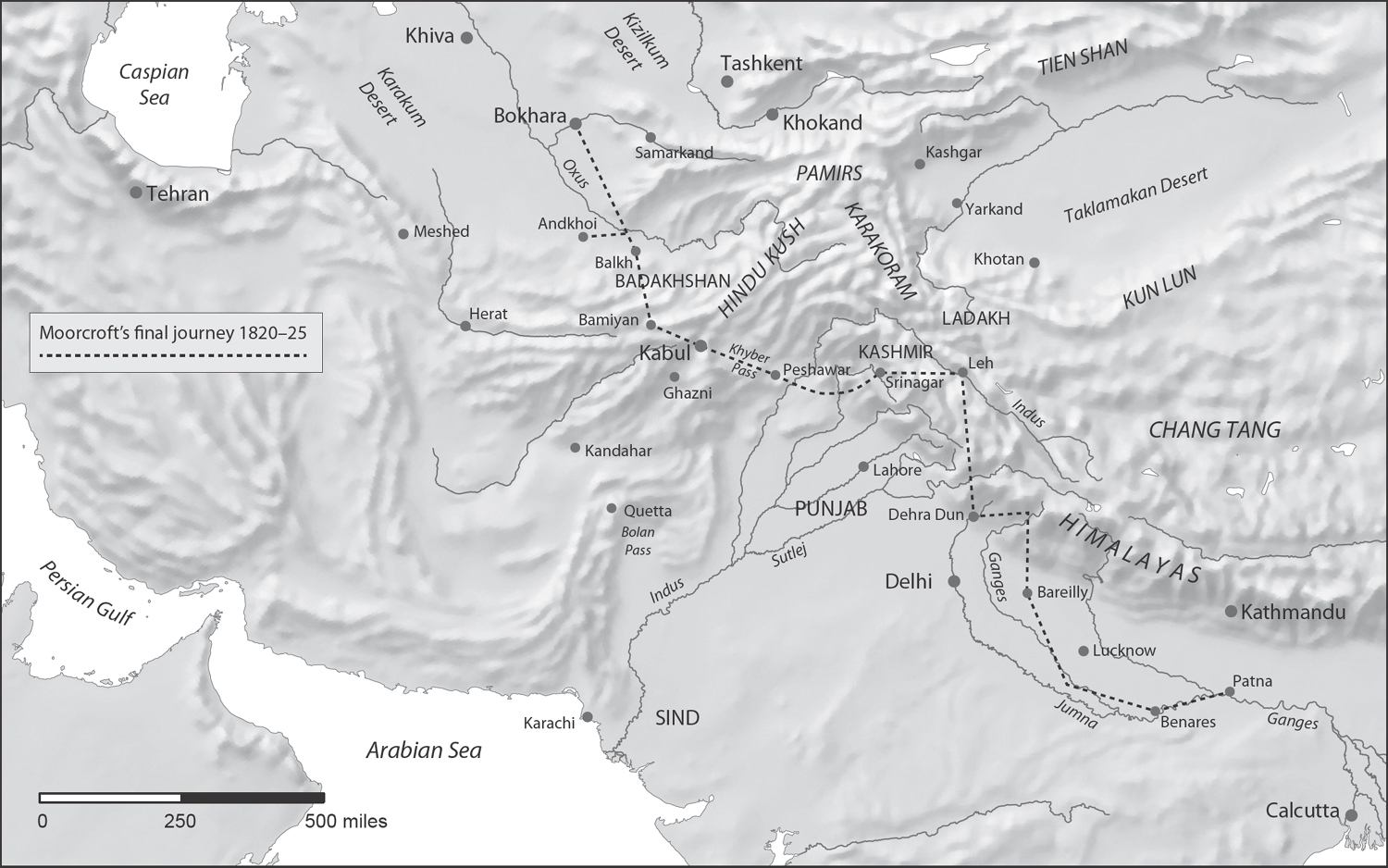

Map 1a. Central Asia, Tibet and India in the nineteenth century

Map 1b. Central Asia, Tibet and India in the nineteenth century

Introduction

The exploration and mapping of Asia and its subsequent carve-up by competing empires make up a fascinating part of its recent history. Most of this activity occurred during the nineteenth century, when large portions of its vast terra incognita previously left blank on maps, or simply marked Unexplored, were finally filled in. The continent would reluctantly reveal its mysteries: a myriad of people and cultures; and, inland, an extreme geography and weather, far removed from the moderating effects of any ocean. This was a time when large parts of the world and its people remained little known to Europeans, and the desire for geographical knowledgetranslated into books and mapswas an end in itself. The quest for adventure too, even at great personal risk, needed no further explanation or justification.

Although this book is set within Asia, it has a sharper focus. It will zoom in on an arc of countries on Indias northern borders. If one were to draw this arc centred on the old Mughal capital of Delhi, it would encompass, starting from the west, Persia (today Iran), then Afghanistan, Western Turkestan (later known as Russian Turkestan), Eastern Turkestan (also known as Chinese Turkestan) and finally Tibet to the east.

For Indias neighbours along the arc, this period would have an added twist. It was here that a contest of high stakes and espionage, referred to as the Great Game, was played out between two of the most powerful empires of the dayGreat Britain and Imperial Russia. Both sides eagerly sought out information about these borderlands, but some countries such as Tibet were closed off to foreigners for the best part of the century. Others such as Afghanistan and Turkestan were off limits too, but in their case this was due to the dangers travellers faced in these often lawless regions infested by bandits. Travel was even more hazardous for Christian Europeans in Muslim lands as local tribesmen considered them non-believers and they ran the real risk of being killed out of hand. Despite these difficulties, there was a desperate need for competing powers to explore and map these regions, both for offensive and defensive purposes. Indeed, the first need of an army in a strange land is a reliable map. They obtained this intelligence by employing explorers and spies, although in many cases the line between the two was blurred, or simply did not exist.

As the Great Game encompasses such a large subject area, this book will limit its scope to the defence of India against the threat of an overland invasion. Within its borders, the British could readily explore and map the entire subcontinent through the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India (the GTS). Outside these borders, they undertook this work primarily with the help of two distinct groups: a band of army officers engaged in playing the Great Game; and an obscure group of natives employed by the GTS, who would come to be known as the Pundits.

Both the Great Game and the Survey of India involved a multitude of players from several countries, from the political and military establishments. To avoid overwhelming the reader with the many names, ranks and titles of the participants involved, as well as the numerous place names and dates, our book will mention just the main ones, as far as possible.

A timeline of the key events covered, highlighting their relationship, is shown at the end of the text. But this book is not meant to be a detailed historical study of these topicsthere are specialist texts already available which do this well enough. Rather, it tells the true story of a group of extraordinary explorers, spies and map-makers, who, though perhaps forgotten today, are its real heroes.

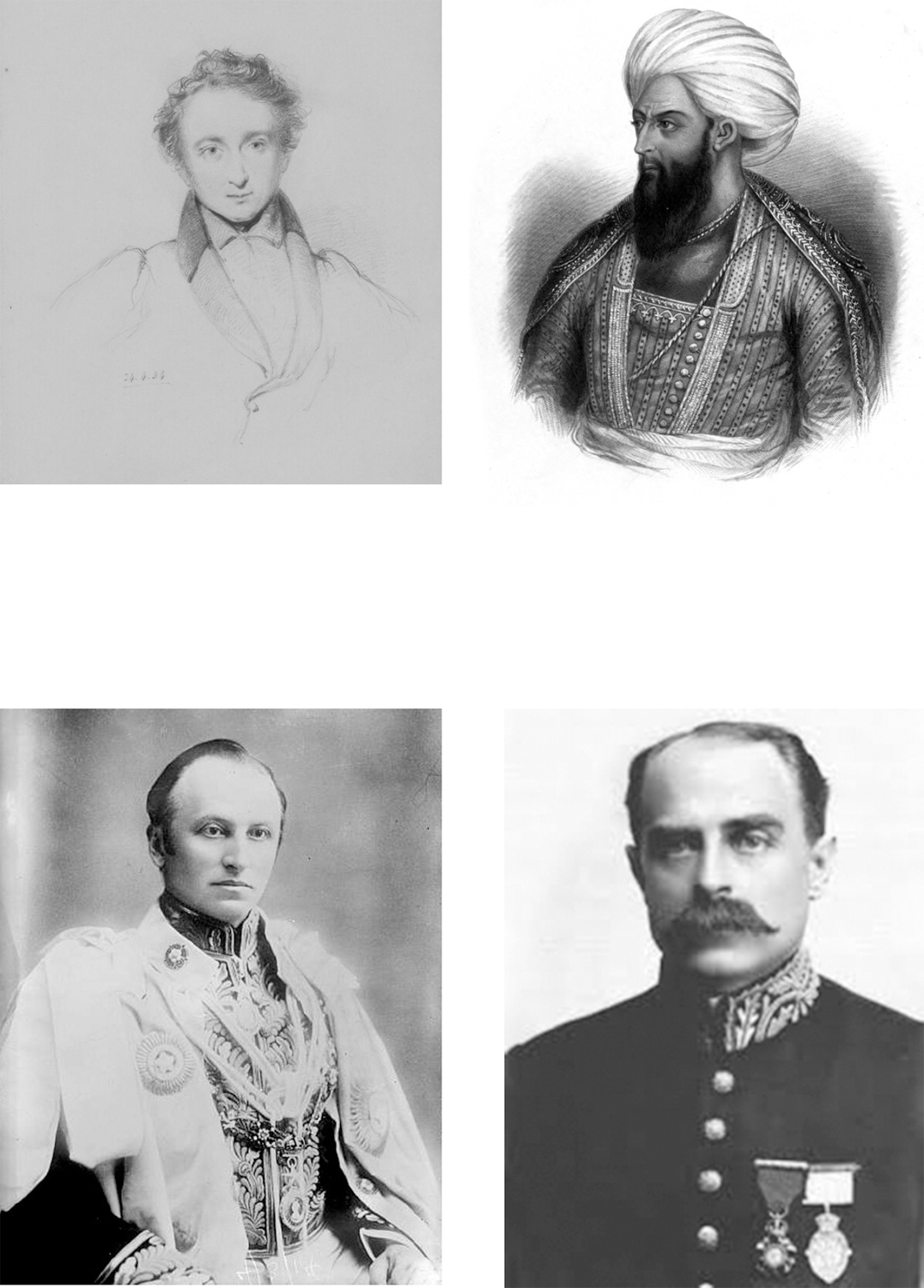

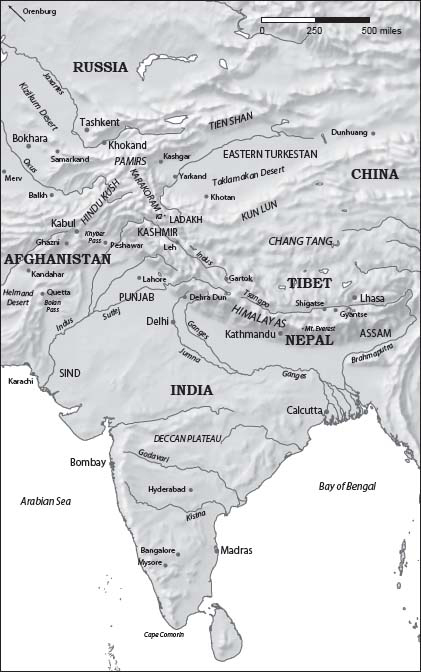

Players who shaped the Great Gameclockwise from top left: Alexander Burnes, Dost Mohammed, Francis Younghusband and Lord Curzon.

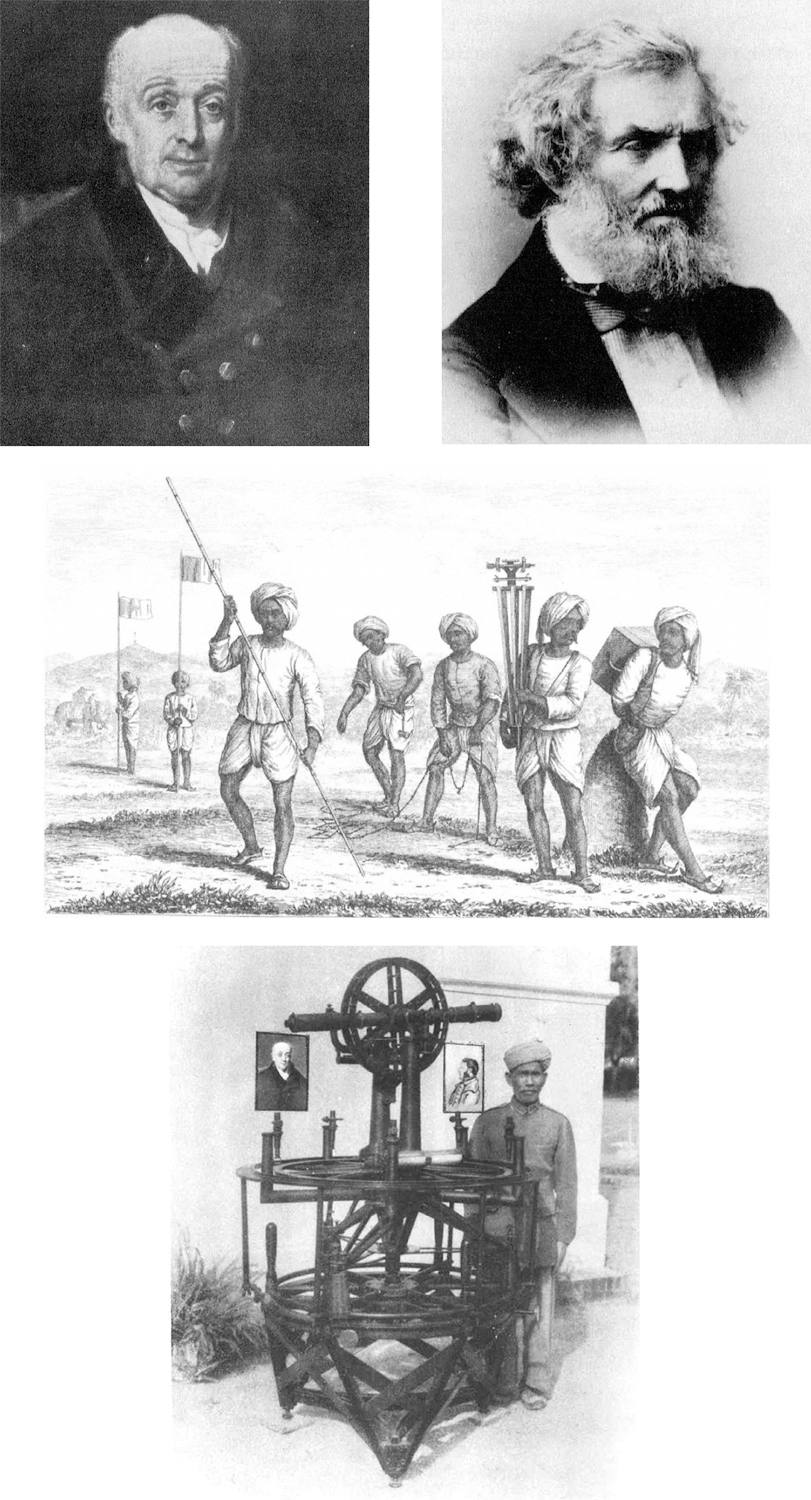

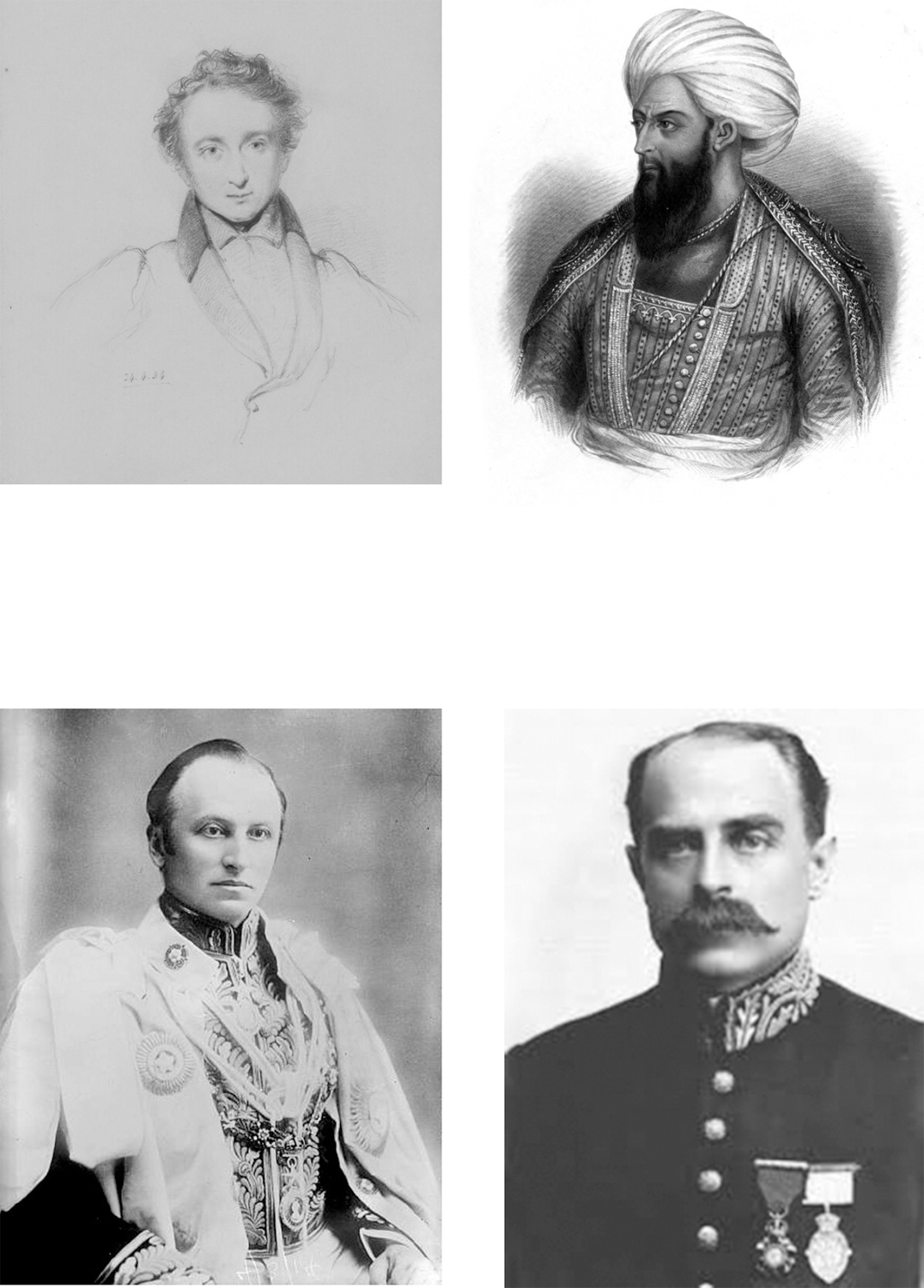

Survey of India employees and equipmentclockwise from top left: William Lambton, George Everest, the Great Theodolite and the Khalasis.

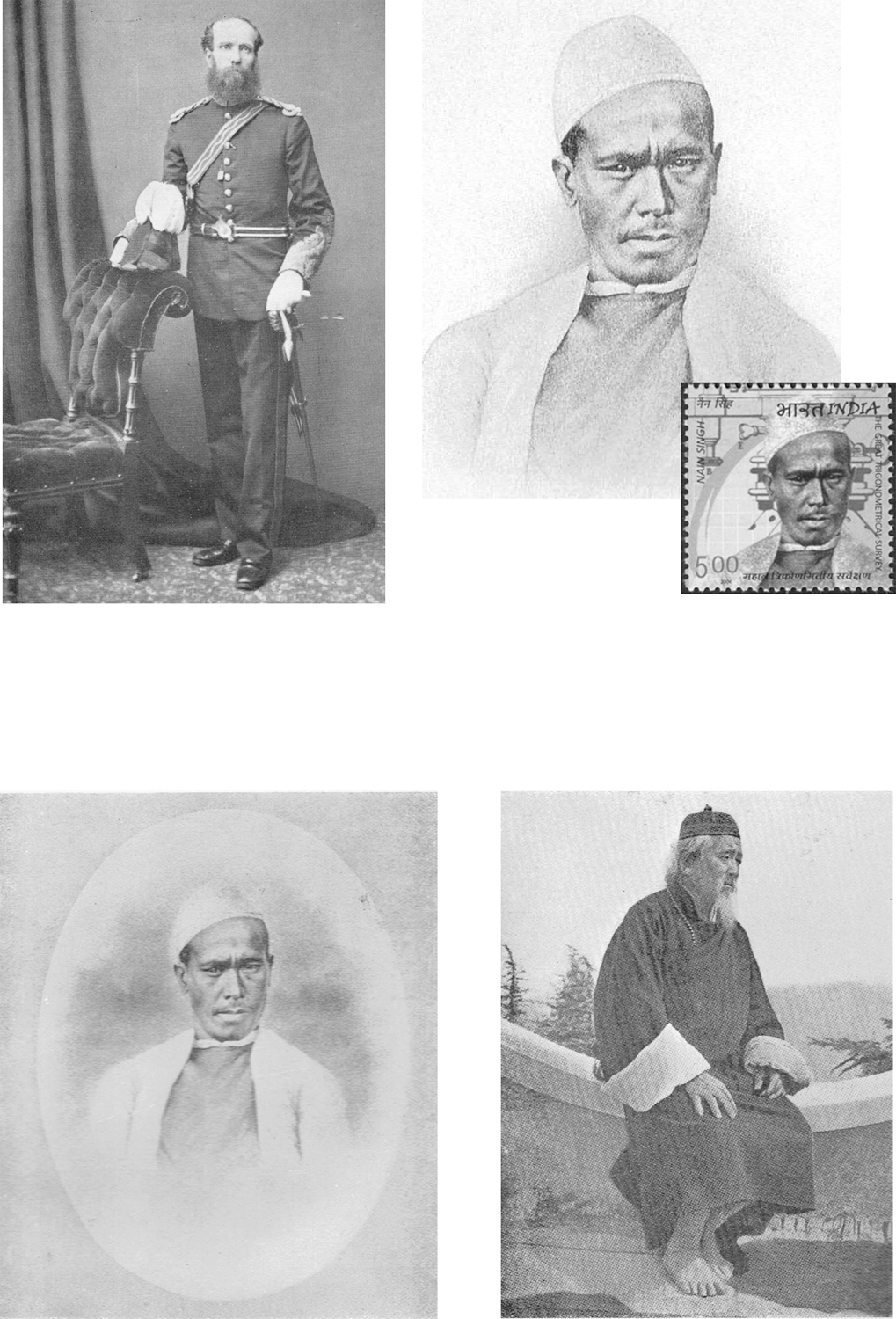

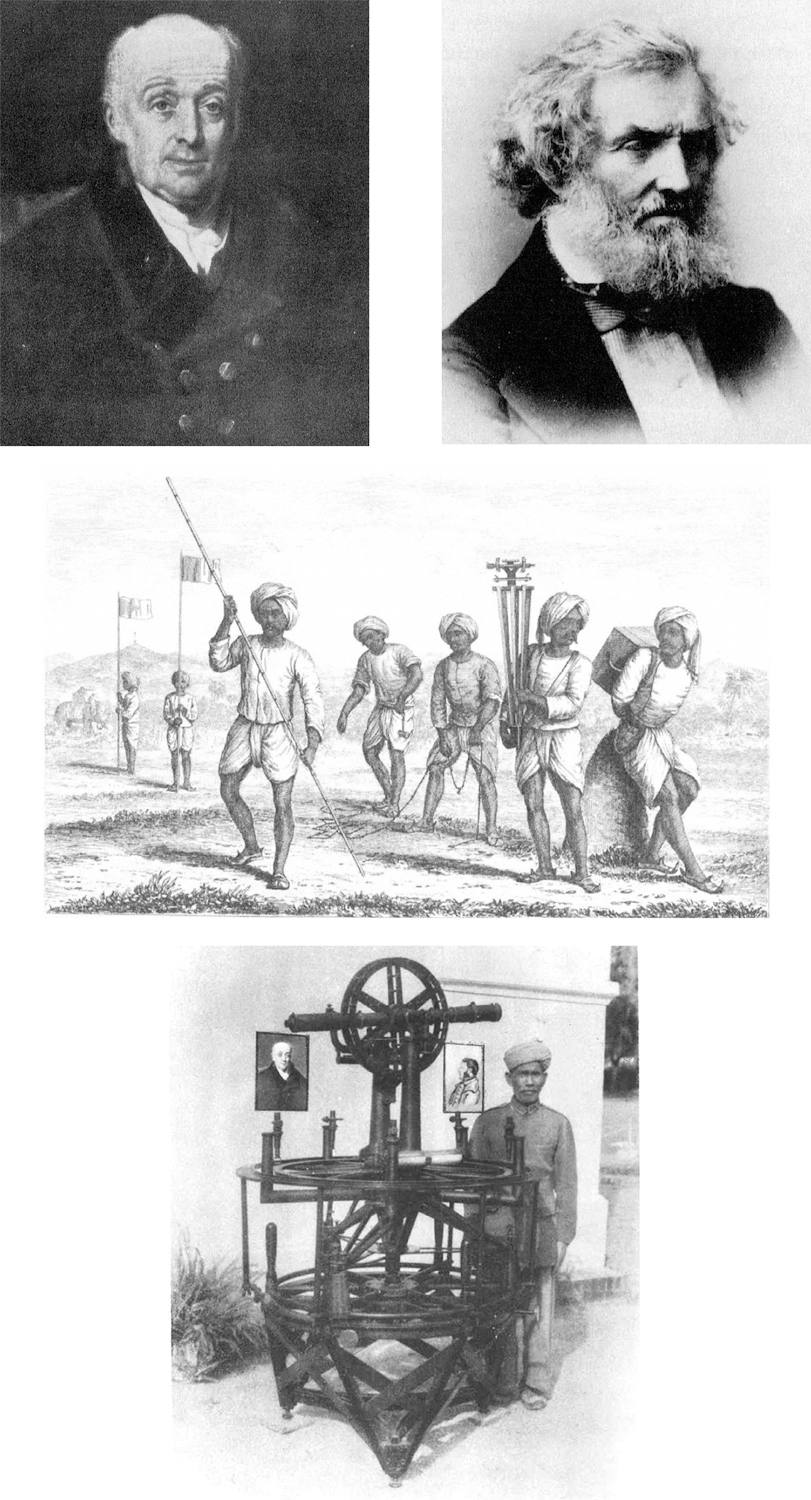

Pundits of the GTS and their founderclockwise from top left: Thomas Montgomerie, Nain Singh (and again on Indian postage stamp), Kintup and Kishen Singh.

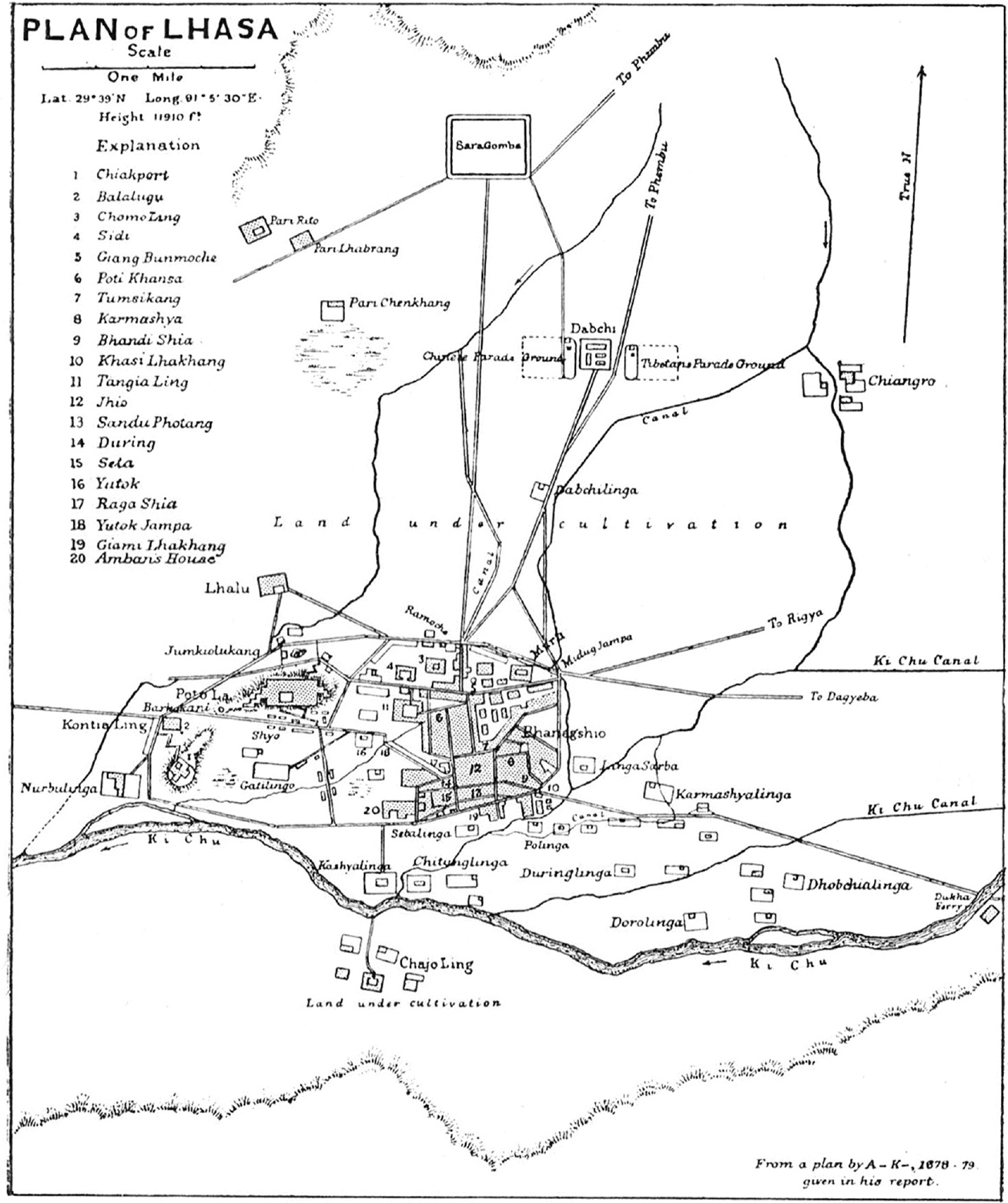

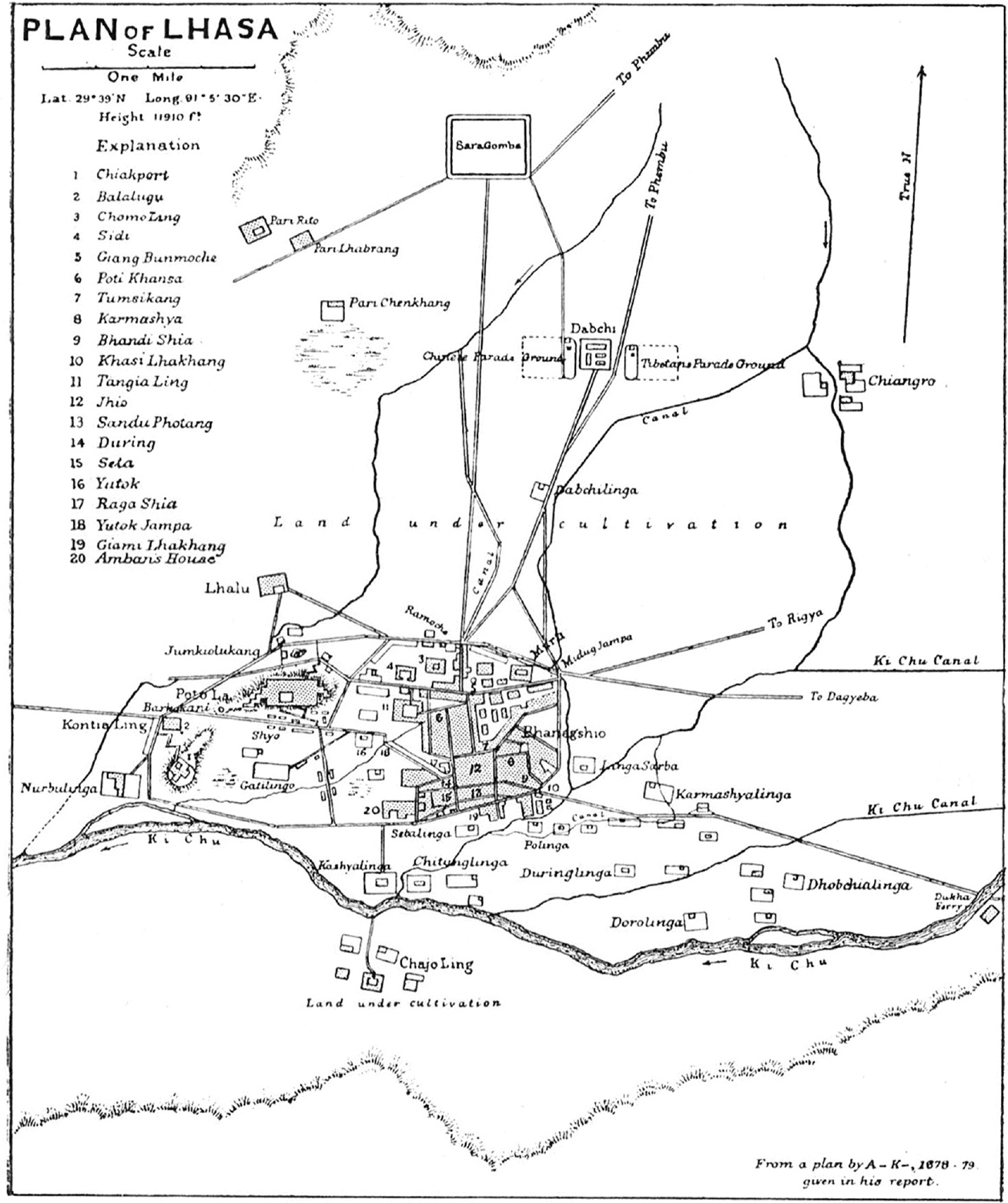

Plan of Lhasa by Kishen Singh (codenamed A-K).

PART ONE

THE GREAT GAME BEGINS

Now I shall go far and far into the North, playing the Great Game.

Rudyard Kipling, Kim

Map 2. Central Asia: showing the final journey of William Moorcroft