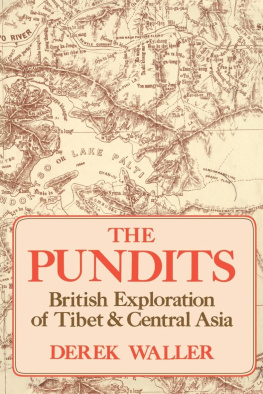

THE PUNDITS

For Penny

THE PUNDITS

British Exploration of

Tibet and Central Asia

DEREK WALLER

Publication of this volume was made possible in part

by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 1990 by The University Press of Kentucky

Paperback edition 2004

The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Maps in this book were created by Lawrence Brence.

Relief rendering from The New International Atlas 1988

by Rand McNally & Co., R.L. 88-S-194.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Waller, Derek J.

The Pundits : British exploration of Tibet and Central Asia / Derek Waller.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-8131-1666-X (alk. paper)

1. Asia, CentralDescription and travel. 2. Tibet (China)Description and

travel. I. Title.

DS327.7.W35 1990

958.03dc20 90-32802

CIP

Paper ISBN 0-8131-9100-9

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

Contents

Maps

Preface

I first became aware of the activities of the pundits in the course of relatively casual reading about the history and politics of Tibet. I discovered that many authors had referred, but only rather briefly, to their exploits. This book will, I hope, go some way toward assigning to these Indian explorers, and to the British officers of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, their rightful place in the history of the exploration of Tibet and Central Asia.

A number of libraries and archives have been vital in supplying material for this book. I should like to give particular thanks to the staff of the India Office Library and Records; the Jean and Alexander Heard Library of Vanderbilt University; the Library and Archives of the Royal Geographical Society; and the British Library. I am also pleased to acknowledge assistance from the library of the University of Leeds, the archives of the Royal Society, Cambridge University Library, and the Public Records Office.

The staff of the National Archives of India in New Delhi were helpful in allowing me to see many volumes in the Dehra Dun series of the Survey of India Records. Unfortunately, the government of India does not permit inspection of all the volumes in this series (or, at least, it did not when I visited the archives in 1981).

The fifth and final volume of Colonel R.H. Phillimores Historical Records of the Survey of India, 1844-1861 (Dehra Dun, 1968) is a difficult book to come by. The work was apparently never actually issued, and only a few copies, which were sent out in advance of publication, are known to be extant. I must therefore express my gratitude to the Royal Engineers Corps Library at Brompton Barracks, Chatham, who kindly made a copy of volume five available to me.

A number of people were generous in their comments on various sections of the manuscript. For their assistance, I am indebted to Gary Alder (who also provided me with copies of some documents), Felicity Browne, Scott Colley, Faith Evans, Peter Hopkirk, and Nicholas Rhodes. In addition to commenting on the manuscript, Nicholas and Deki Rhodes also provided a great deal of information concerning Rinzing Namgyal and Ugyen Gyatso and gave me illustrative material on these two explorers, some of which is reproduced in the text. I also thank Henry Brownrigg of London, owner of the surveying instrument inscribed to Nain Singh, for allowing it to be photographed.

A grant enabling me to travel to New Delhi was given by the University Research Council of Vanderbilt University, and financial assistance toward publication was provided by the Graduate School of the University. I am more than happy to acknowledge both awards.

I am also indebted in other ways to Howard Boorman, the late Forrestt Miller, Bert Pullen, David Snellgrove, and Hugh Tinker. Special thanks to Tommye Corlew, who uncomplainingly deciphered my handwriting, typed, retyped, and typed again.

ONE

The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India

On a September day in 1863, a Moslem named Abdul Hamid entered the Central Asian city of Yarkand. Disguised as a merchant, Hamid was actually an employee of the Survey of India, carrying concealed instruments to enable him to map the geography of the area. Hamid did not live to provide a firsthand account of his travels. Nevertheless, he was the advance guard of an elite group of Indian trans-Himalayan explorersrecruited, trained, and directed by the officers of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of Indiawho were to traverse much of Tibet and Central Asia during the next thirty years.

In the public documents of the Survey of India, these men came to be called pundits or native explorers, but in the closed files of the government of British India, they were given their true designation as spies or secret agents. The use of these agents was sanctioned in the 1860s only after the closing of the borders of Tibet to foreigners, the deaths of several European explorers in Central Asia, the unwillingness and inability of the Chinese authorities to make provision for British travelers, and decades of reluctance by the government of India to allow technically qualified Indians to survey beyond the frontier.

As they moved northward within the Indian subcontinent, the British demanded precise frontiers and sought orderly political and economic relationships with their neighbors. The British were also becoming increasingly aware of and concerned by their ignorance of the geographical, political, and military complexion of the territories beyond the mountain frontiers of the Indian empire. This was particularly true in the case of Tibet. Tibet was certainly the highest, and arguably the most remote and inaccessible, country in the world. The deserts of Turkestan spread to the north, and on the south and west stretched the vast ranges of the Himalayan chain. These could be crossed, but with difficulty, as even the passes were at altitudes in excess of 16,000 feet. To the east, Tibet could be entered from China but only by crossing serried ridges of mountains, running in a north-south direction. Very little was known of the countrys geography, not even the exact position of its capital, Lhasa. There was speculation as to the route of the Tsangpo, its major river, and whether the Tsangpo flowed into India as the Brahmaputra or the Irrawaddy. The true sources of the Tsangpo and Indus rivers were still unknown. The best available map was one made on the basis of measurements taken by two Tibetan lamastrained as surveyors by Jesuits in Pekingand drawn up in 1717.