Know

That on the summit whither thou art bound

A geographic Labourer pitched his tent,

With books supplied and instruments of art,

To measure height and distance; lonely task,

Week after week pursued!

From Written with a slate pencil on a stone

on the side of the mountain of Black Comb,

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH , 1818

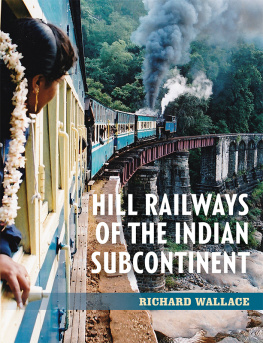

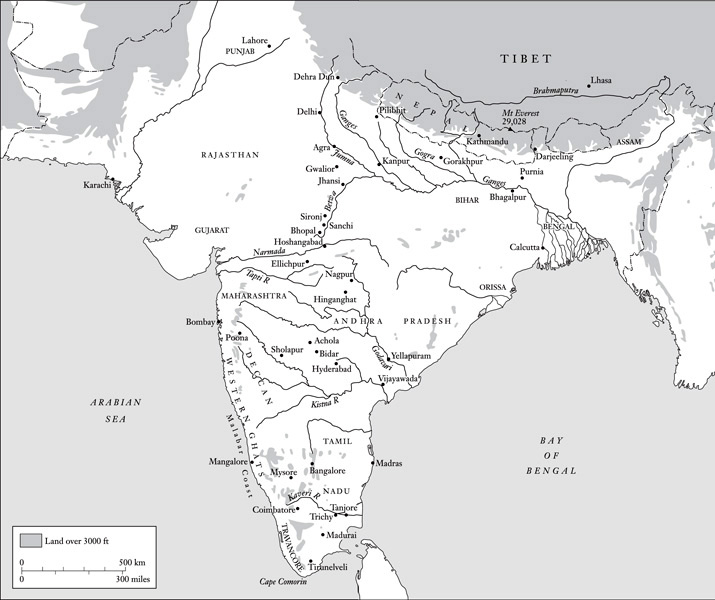

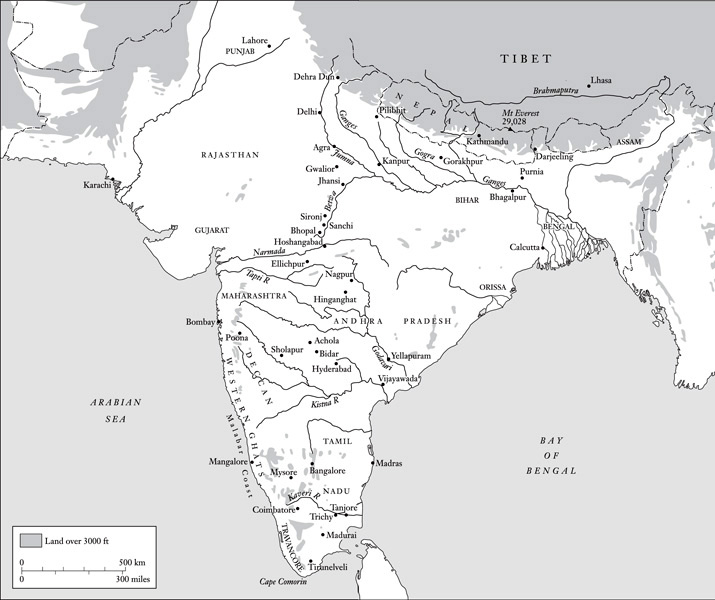

India

Some proper names in the text, especially place-names, will appear to be mis-spelled. This may be because a spelling acceptable to everyone has been hard to establish; or it may be because I have adopted some nineteenth-century spellings in order to be consistent with those used in the quoted extracts (e.g. Kistna for Krishna, Siwaliks for Shivaliks, Ganges for Ganga, etc.). I trust that purists will show indulgence and that all the names are at least recognisable. In the case of the Bengali genius Radhanath Sickdhar, the spelling is that which he himself used, however improbable it now looks.

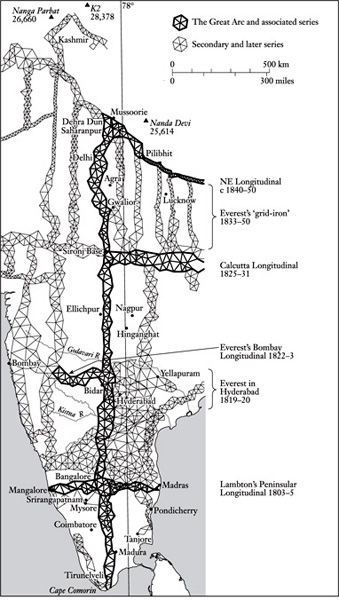

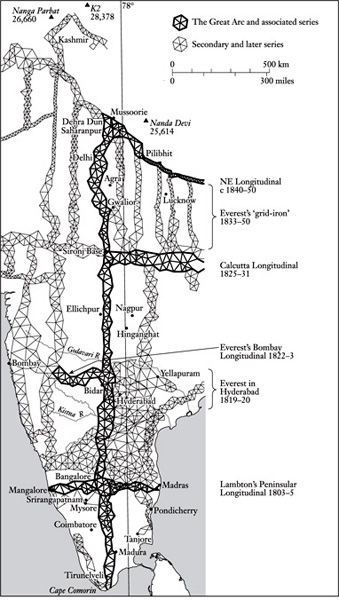

THE GREAT ARC AND ASSOCIATED SERIES

Pressed about why Mount Everest is so named I would once, perhaps like most people, have come up with the explanation that it was as good a name as any. For a geographical feature of such obvious permanence and precedence, Everest seems to say it all. Up there, more aloof from the bustle of life than anywhere else on earth, the raised snows proffer a pledge of peace, a promise of lasting repose, of being ever-at-rest. Presumably some international body had ordained the name; or perhaps it was a translation of the mountains local title. It scarcely mattered. Either way, it was perfectly acceptable.

But, as I now know, these suppositions were totally wrong. That the worlds highest point is in fact called after George Everest, a controversial British Colonel who had never even seen the mountain, let alone climbed it, first dawned on me when I was writing a book about the exploration of Kashmir. Everest did not feature in the region, either as man or mountain, but an institution, dear to the Colonels heart and known as the Survey of India, did. Most of Kashmir, including the Karakoram mountains, had first been measured and mapped by men of the Indian Survey. And the Survey being a government department within British Indias bureaucratic Leviathan, it had generated copious records. To these I turned.

Descriptions of nineteenth-century map-makers hauling their instruments up peaks of unknown altitude proved excellent value. Pelted by hailstones, their tents ablaze from the lightning and their trail obliterated by blizzards, the men of the Survey would dig in and wait. Survival depended on merino drawers, Harris tweeds and alpaca overcoats. Their boots were leather, and they ate mostly rice. They might be marooned for weeks. Then, without warning, in the chill first light of a day when the cloud had unaccountably overslept in the valleys, their patience would at last be rewarded. Sailing a sea of cumulus beneath an azure sky, a line of glistening summits would loom remotely from the ether.

With luck, from two or more of these summits tell-tale pinpricks of light would advertise the presence of other survey teams. If the theodolite was up and ready, sightings would be taken, bearings recorded and signals exchanged. The job was done. A speedy retreat down to the fleshpots of basecamp followed. Then it was on and up to the next peak.

Or so it seemed; but taking such bearings enabled the surveyors to plot the positions and heights of the distant peaks only if the location of their own peak was already known. Otherwise it was like seeking directions from a street map without first having identified your whereabouts. Fixing the positions of the other peaks depended on knowing that of the one from which one observed; its global location in terms of the worlds grid of longitude and latitude had to have been established, and so did its height above sea-level.

Obviously this information could have been obtained from prior observations taken at other vantage points in the rear. And those vantage points could in turn have been similarly established from somewhere in the foothills. But the Himalayas were hundreds of miles from any observatory capable of supplying a fix from astronomy; and they were even further from the sea, in terms of whose mean-level heights were expressed. Working back, then, somewhere there had to have been a starting point, a benchmark series of locations whose co-ordinates and heights had been deduced with a superior precision and were known with unimpeachable certainty.

I asked around, I dug out books, and the trail led back to the Great Arc or, to give it its full title, the Great Indian Arc of the Meridian. I had never heard of it; but the Arc was indeed that benchmark series of locations. It was like the trunk of a tree, the spinal column of a skeleton. It ran for 1600 miles up the length of the subcontinent; and on the inch-perfect accuracy of its plotted locations all other surveys and locations depended.

Clearly, too, the Great Arc was something rather special. The mathematical equations involved in its computation seemed to fill enough volumes to line a library, while the instruments used to gather the raw data were man-size contraptions of cast iron and well-buffed brass which were still lovingly displayed in the Survey of Indias offices.

I ferreted further and I read on. Evidently the Great Arc was way ahead of its time. No scientific undertaking on such a massive scale had previously been attempted. Outside the regulated confines of Bourbon France and Georgian Britain, it was also the most minutely accurate land measurement on record. The accuracy was all-important because the Arc had as much to do with physics as with surveying. It was not simply an attempt to measure a subcontinent but also, incredibly, to measure and compute the precise curvature of the globe.

More prosaically, it was conceived by an elusive genius called William Lambton and was inspired by the first British conquests in the extreme south of India. The year was 1800. In North America Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had yet to set out on their epic journey across the continent. Australia was barely a penal colony; Napoleon still held Egypt; and most of the rest of Africa remained shrouded in that mysterious darkness which was simply Europes ignorance.

Only in Asia, and especially India, was an embryonic imperialism detectable. Already the infant was outgrowing the womb of trade, stretching and kicking prodigiously, and taking its first unsteady strides towards dominion. Just so the Great Arc. Mirroring the progress of empire, it would forge tentatively and then inexorably inland. During forty years of high-risk travel, ingenious improvisation and awesome dedication it would come to embrace the entire length of India. And when Lambton, its endearing founder, died in central India, it would be carried to its grand Himalayan finale by the bewhiskered and cantankerous martinet who was Colonel George Everest.

At the time the scientific world was frankly amazed. The Arc was hailed as one of the most stupendous works in the whole history of science. It was as near perfect a thing of its kind as has ever been undertaken. Lambton and Everest had done more for the advancement of general science than any other body of military men. Their celebrity was assured. Lambton was internationally fted. George Everest was knighted by Queen Victoria; and in his honour that peak, whose discovery and measurement the Arc had made possible, was duly named.