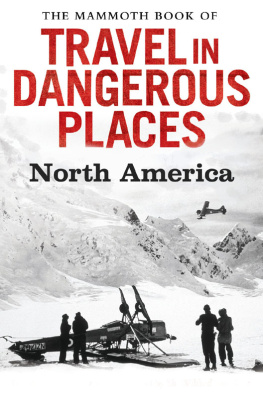

The Mammoth Book of

TRAVEL IN DANGEROUS PLACES PRESENTS

North America

Edited by

John Keay

Constable & Robinson Ltd

5556 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2012

Collection and editorial copyright John Keay, 1993

Content published as The Robinson Book of Exploration (Robinson, 1993). Published as The Mammoth Book of Travel in Dangerous Places (Robinson, 2010).

First Crossing of America, Alexander Mackenzie.

Taken from Voyages from Montreal on the River St Laurence through the Continent of North America to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans (Cadell & Davies, 1801)

Meeting the Shoshonee, Meriwether Lewis.

Taken from History of the Expedition of Captains Lewis and Clark (A. C. McClurg, 1903)

The right of John Keay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication

Data is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-47210-008-5 (ebook)

CONTENTS

First Crossing of America

Alexander Mackenzie

Meeting the Shoshonee

Meriwether Lewis

FIRST CROSSING OF AMERICA

Alexander Mackenzie

(c.17551820)

Endowed by nature with an acquisitive mind and an enterprising spirit, Mackenzie, a Scot engaged in the Canadian fur trade, resolved, as he put it to test the practicability of penetrating across the continent of America. In 1789 he followed a river (the Mackenzie) to the sea; but it turned out to be the Arctic Ocean. He tried again in 1793 and duly reached the Pacific at Queen Charlotte Sound in what is now British Columbia. Although this was the first recorded overland crossing of the continent, Mackenzie was not given to trumpeting his achievement. In his narrative it passes without celebration and very nearly without mention.

J uly 1793 At one in the afternoon we embarked, with our small baggage, in two canoes, accompanied by seven of the natives. The stream was rapid, and ran upwards of six miles an hour. We proceeded at a very great rate for about two hours and an half, when we were informed that we must land, as the village was only at a short distance. I had imagined that the Canadians who accompanied me were the most expert canoe-men in the world, but they are very inferior to these people, as they themselves acknowledged, in conducting those vessels.

Some of the Indians ran before us, to announce our approach, when we took our bundles and followed. We had walked along a well-beaten path, through a kind of coppice, when we were informed of the arrival of our couriers at the houses, by the loud and confused talking of the inhabitants. As we approached the edge of the wood, and were almost in sight of the houses, the Indians who were before me made signs for me to take the lead, and that they would follow. The noise and confusion of the natives now seemed to increase, and when we came in sight of the village, we saw them running from house to house, some armed with bows and arrows, others with spears, and many with axes, as if in a state of great alarm. This very unpleasant and unexpected circumstance, I attributed to our sudden arrival, and the very short notice of it which had been given them. At all events, I had but one line of conduct to pursue, which was to walk resolutely up to them, without manifesting any signs of apprehension at their hostile appearance. This resolution produced the desired effect, for as we approached the houses, the greater part of the people laid down their weapons, and came forward to meet us. I was, however, soon obliged to stop from the number of them that surrounded me. I shook hands, as usual with such as were the nearest to me, when an elderly man broke through the crowd, and took me in his arms; another then came, who turned him away without the least ceremony, and paid me the same compliment. The latter was followed by a young man, whom I understood to be his son. These embraces, which at first rather surprised me, I soon found to be marks of regard and friendship. The crowd pressed with so much violence and contention to get a view of us, that we could not move in any direction. An opening was at length made to allow a person to approach me, whom the old man made me understand was another of his sons. I instantly stepped forward to meet him, and presented my hand, whereupon he broke the string of a very handsome robe of sea-otter skin, which he had on, and covered me with it. This was as flattering a reception as I could possibly receive, especially as I considered him to be the eldest son of the chief. Indeed it appeared to me that we had been detained here for the purpose of giving him time to bring the robe with which he had presented me.

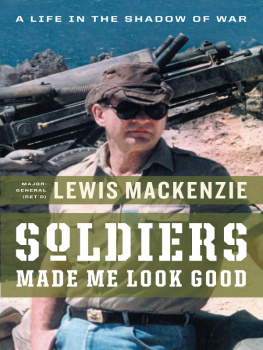

Alexander Mackenzie. From George Bryce The Makers of Canada: Mackenzie, Selkirk, Simpson, London, 1905.

The chief now made signs for us to follow him, and he conducted us through a narrow coppice, for several hundred yards, till we came to an house built on the ground, which was of larger dimensions, and formed of better materials than any I had hitherto seen; it was his residence. We were no sooner arrived there, than he directed mats to be spread before it, on which we were told to take our seats, when the men of the village, who came to indulge their curiosity, were ordered to keep behind us. In our front other mats were placed, where the chief and his counsellors took their feats. In the intervening space, mats, which were very clean, and of a much neater workmanship than those on which we sat were also spread, and a small roasted salmon placed before each of us. When we had satisfied ourselves with the fish, one of the people who came with us from the last village approached, with a kind of ladle in one hand, containing oil, and in the other something that resembled the inner rind of the cocoa-nut, but of a lighter colour; this he dipped in the oil, and, having eat it, indicated by his gestures how palatable he thought it. He then presented me with a small piece of it, which I chose to taste in its dry state, though the oil was free from any unpleasant smell. A square cake of this was next produced, when a man took it to the water near the house, and having thoroughly soaked it, he returned, and, after he had pulled it to pieces like oakum, put it into a well-made trough, about three feet long, nine inches wide, and five deep; he then plentifully sprinkled it with salmon oil, and manifested by his own example that we were to eat of it. I just tasted it, and found the oil perfectly sweet, without which the other ingredient would have been very insipid. The chief partook of it with great avidity, after it had received an additional quantity of oil. This dish is considered by those people as a great delicacy; and on examination, I discovered it to consist of the inner rind of the hemlock tree, taken off early in summer, and put into a frame, which shapes it into cakes of fifteen inches long, ten broad, and half an inch thick; and in this form I should suppose it may be preserved for a great length of time. This discovery satisfied me respecting the many hemlock trees which I had observed stripped of their bark.

Next page