Routledge Revivals

THE LAND OF TIMUR

The Land of Timur

Recollections of Russian Turkestan

By

A. Polovtsoff

With Ten Illustrations By

B. Litvinoff

And A Map

First published in 1932 by Merthuen & Co. Ltd.

This edition first published in 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1932 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under ISBN: 32025475

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-55301-9 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-203-70475-2 (ebk)

THE LAND OF TIMUR

THE LAND OF TIMUR

RECOLLECTIONS OF RUSSIAN TURKESTAN

BY

A. POLOVTSOFF

WITH TEN ILLUSTRATIONS BY

B. LITVINOFF

AND A MAP

First Published in 1932

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

To

N.N.

By Way of Dedication

ONCE, long ago, we spoke of Samarcand. Afterwards I began thinking what pleasure it would give me to tell you more about my life in Turkestan.

The idea haunted me, so I jotted down some of the pictures which arose before me whenever I recalled that Paradise on Earth; and little by little the following pages were written. Of course, I realize that I had no business to misbehave in that way. I know that my English is far too clumsy, quite powerless, in fact, to describe the subtle and varied charm of Central Asia; and that these unpretending sketches are therefore sorely deficient in those merits which they ought to have possessed if they were to deal at all adequately with their subject. Excuse a foreigner. In using for my medium a language I had better have left alone, I merely thought of you and of amusing you. I aimed at making a film pass before your eyes, and I hoped that you would not be chilled by my enthusiasm for a country which you, of all humans, would love if you knew it.

But is it still the same? It is many years now since I saw the places I describe, and in that time the immutable East has proved its mutability. The so-called Communists from Moscow have created in Samarcand an important propaganda-school for spreading revolution in Asia, and the beautiful old mosques are used, I hear, for expounding to gaping audiences the gospel of Marx. In what monstrously modernized Persian or Turki dialect it is done, I shudder to think. And what may be the appearance of Ogpu agents under the tiles and marbles of Timur's archways, I cannot imagine; Providence has spared me these sights. The Ameer of Bokhara (the son of the one I knew) is an exile, and I have no information as to what has happened and what is happening in his country. Nevertheless, I have preserved the present tense in most of these sketches. I could not help it, and I do not feel that I can alter it. My hope is that some, at least, of the beauty and originality of Russian Central Asia may, even in the hands of super-experts in destruction, not yet have been destroyed.

A. P.

PARIS, 1932

List of Illustrations

SKETCH MAP OF THE LAND OF TIMUR

(From a drawing by A. E. Taylor)

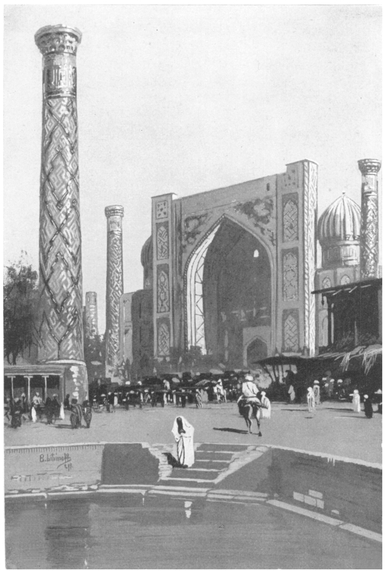

- REGHISTAN, SAMARCAND

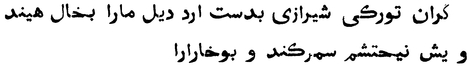

THIS is not a technical work. In transcribing the names of Asiatic people and places I have not considered the most correct orthography, but have tried to render as closely as possible the local pronunciation. I have, however, used 'Bokhara', because that is the form to which Western people are accustomed, though the real name is 'Boohar':

Shirazee (ah, the rogue!) take my heart in

your hand!

For one mole on your cheek I would gladly

give up

Both Bokhara and Samarcand.

Persian distich

I

The Reghistan Mosques

MILE after mile of a dreary, dusty road. Nothing but the steppe, pale grey and limitless under the full moon. The hours slip by in monotonous succession, and the frosty November night keeps me awake and shivering in my fur coat. Then something ahead: clusters of bare willows and poplars, low mud-walls, a house or two. Are these the first outskirts of the city that I have made up my mind to reach at all costs to-night? No; it is only another post-station, where three fresh horses will be harnessed to my primitive, springless carriage. There is a delay. The station-master tries to prevent my going on and insists upon arguing; he wants me to wait here till daylight, as there are suspicious characters on the road, stray workmen from the gangs which are building the railway; besides, the river ahead is swollen by the recent rains, and if my cart overturns, who will help me at such a late hour? Tiresome old man! As if his grumbling could stop me! Again the troika jogs on through the barren waste.

Of course the river was pretty bad, and unexplained shadows did hover in too close proximity at a place where the road was broken, but they vanished at once when they saw my revolver gleaming under the bright rays of the moon. So when these foreseen accidents had been left behind, and still no city rose from out of the night, lassitude overtook me, and like the driver, whose bent and silent figure seemed more asleep than awake, I became more and more drowsy till oblivion engulfed me.

Suddenly a wonderful vision nearly made me cry out aloud. Was it a trick of my fancy? Was it solid and real, perhaps a forgotten tale out of the 'One Thousand Nights and a Night'? Or had the very soul of the hoary East clad itself in dreamlike splendour to come out and greet me?

Three perfect mosques standing at right angles along three sides of an admirably proportioned square pointed their domes and their minarets towards the moon. The cool, enamelled surfaces of their portals and walls shimmered in faint blues and greens like the skin of a snake, and the silvery light ran and played over the intricate patterns of the mosaics, shrouding them in a diaphanous, unearthly haze. Towers boldly rose up to the sky; but were they actually formed of stone or brick and fastened with mortar? There they were, standing aslant, like the towers of Pisa or of Bologna, as if deriding the ponderous laws of terrestrial matter. The haughty silence of those lofty shrines created an atmosphere of unreality, which deepened their aloofness, made them no longer human, but nearly divine. Could they have been built by mortals in order to bring mankind together for prayer? Of course not. Clearly they had been piled up out of ghostly gems by fairies or by genii, their wonderful harmony expressing in its mere lines a stronger yearning for heaven than any human works could proclaim.