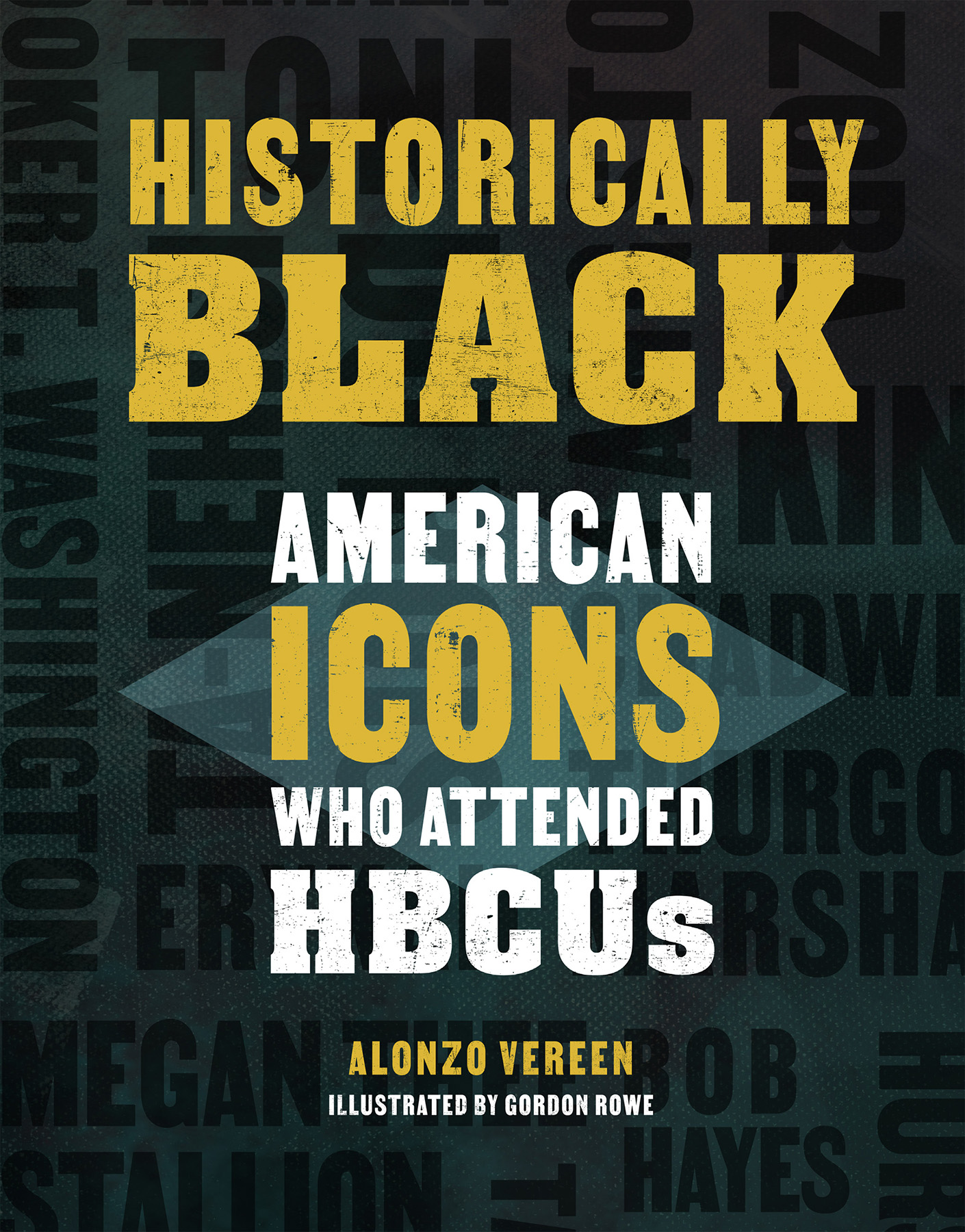

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Published by Running Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Running Press name and logo are trademarks of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

I RECALL, QUITE VIVIDLY, THE FIRST TIME I WALKED ACROSS FAMU S CAMPUS . I was nine years old, so Im certain there are things that went over my head, but the feeling in the airof community, of acceptancehas forever stayed with me.

For a boy born and raised in a migrant community, what I witnessed that day expanded my definition of Blackness. There, before the Biology building, stood a semicircle of Black men in white lab coats debating their points with such quick, impassioned language that I could not keep up. At the base of an oak tree sat a Black woman with a legal pad perched against her arm, the wind tousling her box braids as she studied its yellow pages in deep concentration. Groups of teenagers, nearly indistinguishable from the college students, were clustered throughout the yard with trumpets, clarinets, and snare drums, their basketball shorts and white T-shirts dirtied from band camp. And they were all Black people. Everywhere I looked, my eyes found Black people.

My sister took me to her upper-level Psychology course. It was my first time inside a college classroom, and I was enamored by everything (the desks were so long, so wide! the chair swiveled all the way around!). Her professor walked in (a Black man! with half-moon spectacles!), tossed his spiral notebook on the podium, and launched into a conversation with his students. Id expected a lecture. This was an actual conversation. How could a man who held all the knowledge of his discipline be genuinely interested in what his students thought of the reading? It floored me. When one of his questions stumped his students, he put the question to me (to me!). I cannot for the life of me remember the question, and I cant recall my answer, but I do remember how brightly he smiled afterward. I knew then I had to attend college.

By the time I was old enough to apply, I had turned all my attention to the Ivys. If Harvard did not accept me, then Id settle for Princeton; if not Princeton, then, God forbid, Id have to make do with Yale. Id been educated in predominately Black schools from pre-K to high. I wanted a different experience for college.

Then the unexpected happened. During my sophomore year of high school, my mother passed away. Suddenly, everything I thought I knew about myself felt faulty and unreliable. My town was no longer comforting; it was haunting. I had to leave. College seemed the best option, so I graduated a year early.

Before I began gathering application materials, my AP English teacher pulled me aside (why is it always an AP English teacher?). She mustve sensed the confusion clouding my judgment, because she told me something I have never forgotten: Go where youre wanted, not tolerated. Why was she telling me this now? I wondered. She knew of my Ivy League aspirations. Was this her way of suggesting I did not possess the intellect needed to compete at what I thought was the highest level? Was she trying to recruit me to Fisk, her alma mater? Questions raced, but in the end, I couldnt muster the emotional bandwidth to entertain them. She was the smartest person I knew. I had never not followed her guidance.

My people had absolutely no money. Scholarships were my best option. I applied to as many as I could, to the detriment of my college applications. With time ticking, I applied to only two schools: Morehouse and Howard. The lopsided focus paid off. I got word that Id received the Gates Millennium Scholarship, which would provide full funding for any school in the country; all I had to do was get admitted. Then I heard word from Morehouse and Howard. Id been admitted into both. At the time, one of my closest friends was a student at Morehouse and made quite the persuasive pitchin Atlanta, the guys fell from the sky like manna. Im gay, so there you have it.

I share the full extent of my story not because its unique, but because it mirrors so many of the stories youll encounter here. While these profiles feature celebrated Black educators, scholars, artists, scientists, and athletes, what binds them are the obstacles they had to overcome just to feed their passions. Because of these obstacles, many of the people youll read about never graduated from college. Financial constraints prevented them from obtaining the degrees theyd spent years pursuing. Others had to work multiple jobs while enrolled to cover tuition.

Reaching ones full potential has always been difficult for Black Americans. For centuries, educating Black people was illegal in this country. Concert halls and theater programs had long been the exclusive domain of white people. Collegiate sporting events were segregated for the better part of this countrys history. Yet we found a way, often by establishing our own paths for success at historically Black colleges and universities. HBCUs have been both our springboards and our anchors, propelling us into this countrys cultural center while grounding us in our history.

Historically Black explores what it meant for some of Americas most influential citizens to attend these schools. Their stories are organized into five distinct sections. Each section corresponds with the years they attended college and the major cultural movements that impacted their studies. Determining who to include was a difficult processthere are so many lives intertwined with the legacy of HBCUs that didnt make it into this book. The hope is that this collection not only reflects the range of Black American life, but also the breadth of each HBCUs impact on our nations history. And for any prospective student out there, I say make the leap, because at HBCUs, youre wanted.

I N 1837, THE A FRICAN I NSTITUTEAKA THE I NSTITUTE OF C OLORED Y OUTH opened. Its the first HBCU we know of. Like many HBCUs of its time, the school was not technically a college or university, as it did not grant degrees. It specialized in preparatory programs that taught students how to teach, how to preach, or how to conduct missionary work. Its reputation spread quickly.