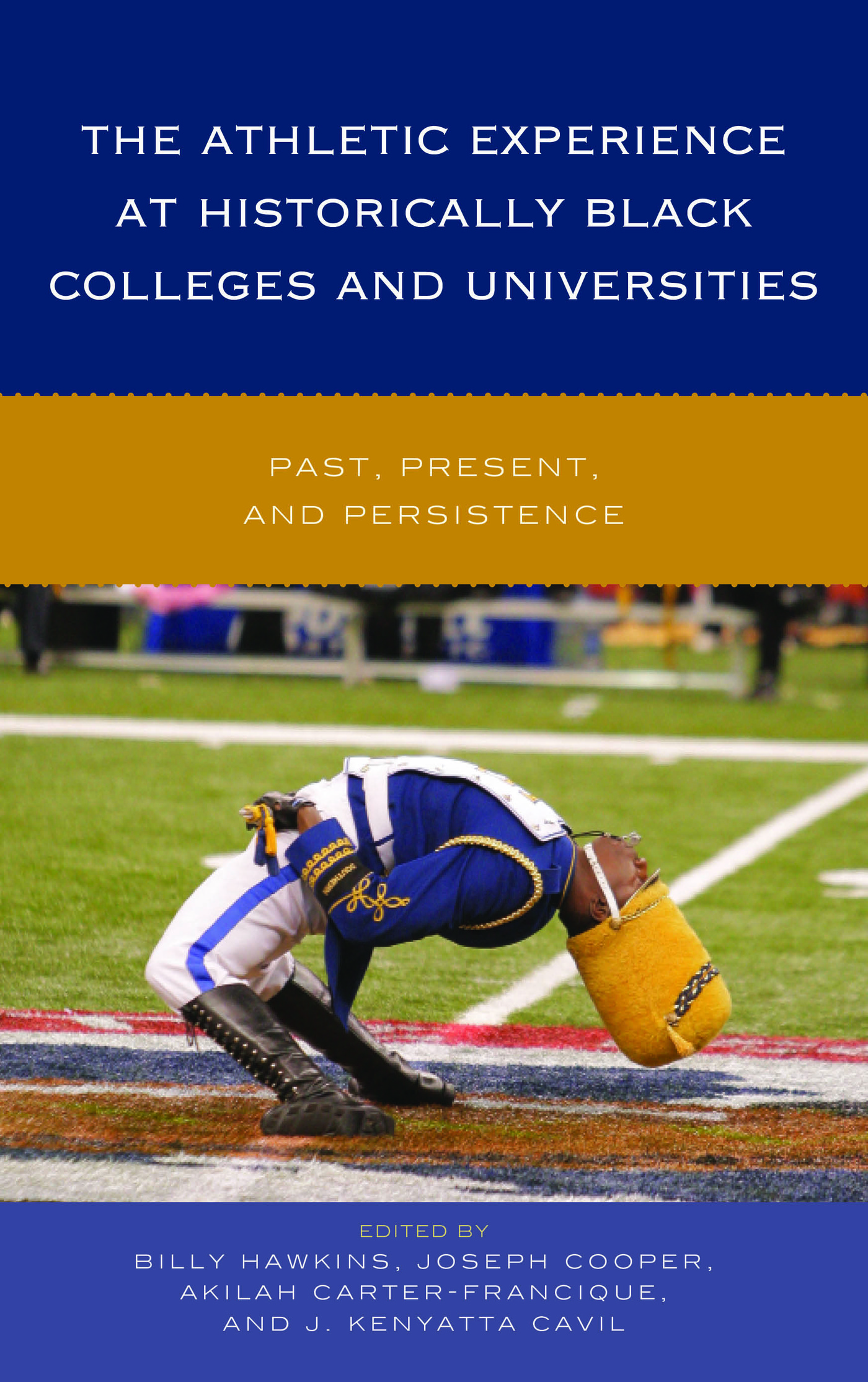

The Athletic Experience at Historically Black Colleges and Universities

The Athletic Experience at Historically Black Colleges and Universities

Past, Present, and Persistence

Edited by

Billy Hawkins

Joseph Cooper

Akilah Carter-Francique

J. Kenyatta Cavil

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2015 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The athletic experience at historically Black colleges and universities : past, present, and persistence / edited by Billy Hawkins, Joseph Cooper, Akilah Carter-Francique, J. Kenyatta Cavil.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-5368-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-5369-8 (ebook)

1. College sportsUnited StatesHistory. 2. African American universities and collegesSports. 3. African American college athletes. 4. College athletesUnited States. I. Hawkins, Billy.

GV351.A74 2015

796.04'30973dc23

2015011440

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Introduction

Billy Hawkins, PhD

The need for black colleges and universities emerged out of the institutional arrangements of the Black Codes in 186566 and during Jim Crow segregation in the late 1800s. Coupled with the dominant ideology that blacks were intellectually inferior, as well as laws that prohibited slaves from being educated, these legal forms of segregation placed significant restrictions on blacks economic, political, and educational mobility after the Civil War. However, blacks desire to excel in this country prevailed against these racist practices, and black institutions of higher education became the reservoirs of black intellectual and athletic genius during the late 1800s and throughout the early 1900s.

The financial history of support for institutions offers a truly significant contrast between historically white colleges and universities (HWCUs) and historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). The financial support of these institutions varied from being ventures of Freedmens Societies, black and white religious groups/denominations (e.g., Christian Methodist Episcopal, African Methodist Episcopal, Presbyterian, Quakers), to philanthropists and congressional charters. Therefore, the motives for creating these institutions also varied from a sincere desire to educate blacks in becoming empowered and functional American citizens to one federally mandated due to the Morrill Act in 1890. This legislation produced large land grant institutions and required all southern and border-states to develop separate public black and white colleges or blacks would have to be admitted to existing colleges; or white colleges would have to pay tuition for blacks to attend northern institutions.

There was also variance in the missions of the first black colleges where the foci ranged from liberal arts institutions, to teacher-training colleges, to colleges and universities with an agricultural and mechanical or technical focus. Despite the different contributors to the establishment of black colleges, the variance in motives and missions, it is abundantly clear that black colleges and universities (which will be referred to as HBCUs) became the reservoirs of higher education for blacks, especially since they were denied the opportunity to attend white institutions of higher education, especially in the South.

Despite their historical origins, the recent boycott by athletes at Grambling State University has ignited national discussion and debate about college athletics, specifically, and athletic conditions at HBCUs, in general. This boycott comes at a time when litigation against the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), regarding the use of athletes likenesses and long-term health issues resulting from head injuries, is being discussed in the courts. The decisions in these cases stand to alter the face of collegiate athletics and the business practices of the NCAA indefinitely. Additionally, All Players United is a campaign made by players during the 20132014 season to express their discontent with the NCAAs treatment of athletes. These examples are fueling the national debate about the role of intercollegiate athletics and higher education; especially the role of the commercial spectator sports of football and mens basketball at these institutions.

More specifically, the boycott at Grambling registers as both a triumph and a tragedy. A triumph in regards to athletes, who are often perceived to be politically conservative and socially detached as students, are found taking a stance against injustices they incurred in their athletic working conditions (dilapidated weight rooms, travel arrangements, etc.). A tragedy because of the legacy of the legendary head football coach, Eddie Robinson, the athletic excellence he accomplished during his tenure, and the academic relevance Grambling provided since its inception in 1901. This incident also registers as a tragedy because, according to Johnny C. Taylor, president and CEO of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund:

Grambling is emblematic of a bigger problem. Its not limited to athletics. Dorms have fallen into serious disrepair. Classrooms are in need of updating, and academic programs have suffered. Some schools have had to reduce faculty and staff. To be blunt, its the result of years and years of financial neglect. Some of these schools are in need of a major infusion of cash.

A recent issue involving athletic challenges at HBCUs was the cancellation of the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) championship football game between Winston-Salem State and Virginia State because of an assault on Winston-Salem State quarterback Rudy Johnson by several players from Virginia State. This incident prompted CIAA commissioner Jacqie Carpenter to issue a statement with an explanation for the cancellation and the following call for excellence:

It is important that everyone involved in the CIAA embody our mission every day by acting as upstanding individuals on and off the field. We must work together to hold each other to higher standards of responsible judgment and conduct because we must demand that if we are to succeed.

The cancellation of this championship event is significant beyond the projected economic impact it would have provided for the Winston-Salem, North Carolina, area, but the social and cultural capital this event elicited is immeasurable.

In a broader social context, these occurrences further fueled the debate on the relevance and economic viability of HBCUs. Moreover, since their inception, this nation has made progress in race relations and in electing its first biracial president, thus, the racial climate that give birth to them has changed considerably. Additionally, in light of the financial stability of many of these institutions, and given the state of athletic programs at HBCUs, where several programs have been cancelled (e.g., see Spelman College, Paul Quinn football program), what role do these institutions, in general, play in the scope of this nations goals of increasing educational achievement, thus, improving our global ranking on educational achievement, and more specifically, what role do intercollegiate athletics play in undergirding the mission of these institutions and fostering academic excellence and economic sustainability?

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.