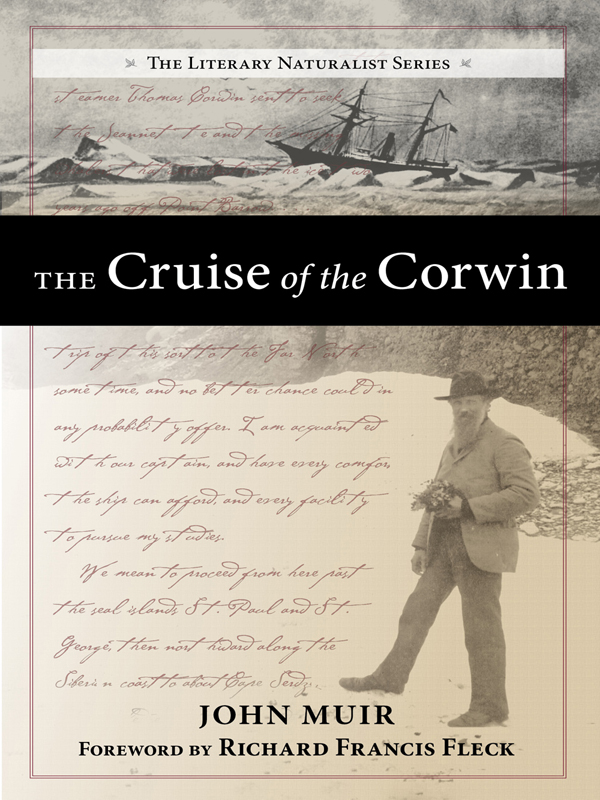

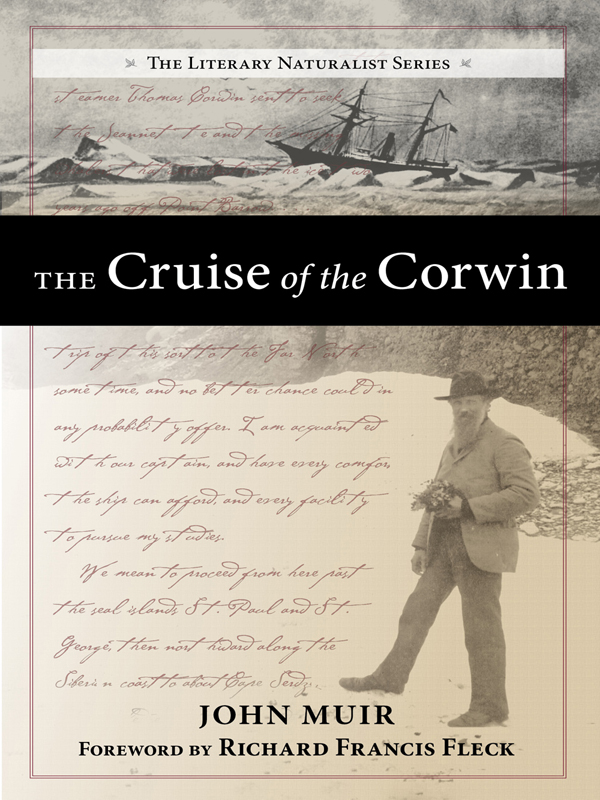

THE Cruise of the Corwin

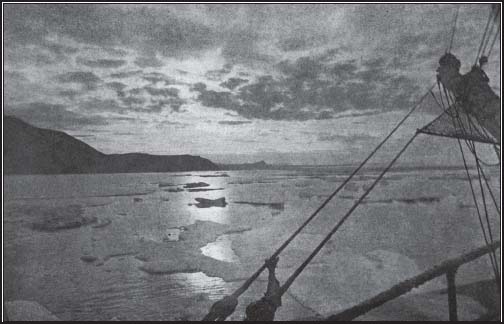

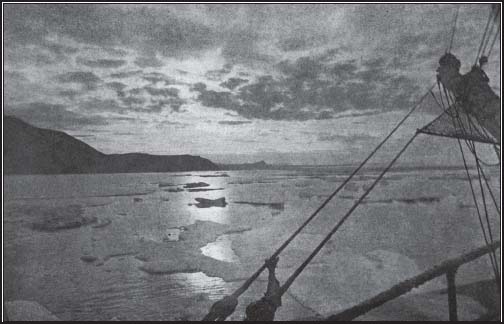

CAPE SERDZEKAMEN, SIBERIA

T HE L ITERARY N ATURALIST S ERIES

THE Cruise of the Corwin

Journal of the Arctic Expedition of 1881 in search of De Long and the Jeannette

JOHN MUIR

Foreword by

RICHARD F. FLECK

OTHER TITLES IN THE SERIES

The Maine Woods

Alaska Days with John Muir

Foreword 2014 by Richard F. Fleck

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

The Cruise of the Corwin was first published by Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1917.

Front cover photos, top: From a photogravure of a painting by G. F. Denny, courtesy of Houghton Mifflin; bottom: John Burroughs and John Muir, probably in Alaska, Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Muir, John, 1838-1914.

The cruise of the Corwin : journal of the Arctic expedition of 1881 in search of De Long and the Jeannette / John Muir ; foreword by Richard Francis Fleck.

pages cm

The Cruise of the Corwin was first published by Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1917Title page verso.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-941821-11-4 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-941821-48-0 (hardbound)

ISBN 978-1-941821-36-7 (e-book)

1. Arctic regionsDiscovery and exploration. 2. Corwin (Ship) I. Title.

G625.M85 2014

979.803dc23

2014017815

Designed by Vicki Knapton

WestWinds Press

An imprint of

P.O. Box 56118

Portland, OR 97238-6118

(503)254-5591

www.graphicartsbooks.com

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

From a photograph

From a photograph by E. S. Curtis

From a photograph by E. S. Curtis

From a photograph

From a photograph by E. S. Curtis

From a photograph

From a photograph by E. W. Nelson

From a photograph by E. W. Nelson

From a photograph by E. S. Curtis

From a photograph by E. S. Curtis

Except as otherwise indicated the illustrations are from sketches by Mr. Muir, the last twelve being reproduced from the cuts in Captain Hoopers official Report of the expedition.

The title-page cut is from Mr. Muirs drawing of Erigeron Muirii, a plant discovered by him near Cape Thompson in northwestern Alaska and named for him by the botanist Asa Gray. This cut appeared in Captain Hoopers Report.

FOREWORD

J OHN MUIR is not generally known for his writings on native cultures of the Arctic regions of Alaska and Siberia; yet his astute observations recorded in The Cruise of the Corwin (published posthumously in 1917) are assuredly worth examining in light of the relationship of these people to their rugged and sublimely awesome environment before and after contact with civilization. Of all Muirs biographers and literary critics, only has Herbert F. Smith made significant commentary on Muirs observations of Inuit (Yupik) and Chukchi cultures. However, Smith, in his book John Muir (1965), asserts that Muirs commentary on Yupik and Chukchi cultures is merely superficial:

A return to the old situation no longer being possible, Muir urges that the government complete the process of civilization for the Eskimos, taking them out of the balance of nature in their environment entirely. Nobody who has read any of Muirs other books could possibly believe that this solution seems ideal to him; but, the degradation of our Eskimos having become an accomplished fact, he can see no other course of action possible.

But, because Muirs commentary, like that of a more recent Scottish writer Duncan Pryde (in his book Nunaga, 1971), suggests that Arctic solutions to Arctic problems can and must be found, his views cannot be categorized as being merely superficial. As Smith deftly points out, Muir fully sympathized with the wilderness way of life, which was and is gravely threatened by forces of civilization. However, rather than completing the process of civilizing all Arctic cultures, Muir, I believe, strongly advocated a maintenance of Arctic cultures through northern and not southern resources.

John Muir agreed in 1881 to sail aboard the Corwin, whose fruitless mission it was to search for the missing scientific research vessel Jeanette, which itself became icebound while exploring the distant and mysterious Wrangell Land in the higher latitudes of the Arctic. As William Frederic Bade points out in his introduction, this cruise would afford Muir the opportunity to examine evidence of glaciation along the Arctic coastlines of Siberia and Alaska. While much attention is paid to such evidence (see Muirs detailed and artistic sketches that Bade incorporated throughout the book), an important element in the book concerns harmonious lifestyle of Inuits and Chukchis, which was in the midst of disruption from the intrusions of the civilized South. Unfortunately a great number of tribal peoples adopted the ways of the white man in mad pursuit of monetary profit by nearly killing off fur-bearing mammals of the North.

On the way north, Muir first encounters Aleut (Unangax) people who are far more civilized and Christianized than any other tribe of Alaska Indians. While they are successful at hunting and fishing, They are fading away like other Indians. The deaths exceed the births in nearly every one of their villages, and it is only a question of time when they will vanish from the face of the earth. It must be pointed out that to note Unangax are vanishing is not quite the same thing as to advocate the process. The main problem with the Unangax from Muirs perspective was alcoholism:

As the Tlingit Indians of the Alexander Archipelago make their own whiskey, so these Unangax make their own beer, an intoxicating drink, which, if possible, is more abominable and destructive than hootchenoo. It is called kvass, and was introduced by the Russians, though the Aleut kvass is only a course imitation of the Russian article, as the Indian hootchenoo is of whiskey.

One poor chap, mentions Muir, would gladly give up his hard-earned savings of $800 from fishing and hunting to by five bottles of whiskey. Hunters and traders desired to create in the natives a dependency on them rather than on nature.

As the Corwin sailed north, Muir met his first Yupik natives at the northwest end of Saint Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea. One of the most striking characteristics of these people was their innate happiness despite their harsh and stormy environment: It was blowing and snowing at the time, and the poor storm-beaten row of huts seemed inexpressedly dreary through the [snow] drifts. Never the less, out of them came a crowd of jolly, well-fed people, dragging their skin canoes over the rim of extended ice.

Next page