We have never needed nature more than now. At a time when our relationship with our home planet is under stress, the positive words of John Muir (18381914) can help us to reconnect, retune, and readjust what it is that we should value for the survival of our species. In 1901 John Muir opened his book Our National Parks with words that might resonate for readers today: Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilised people are beginning to find that going to the mountains is going home. This Scot, transplanted to the USA at the age of eleven by his family to help carve a farm out of the wilds of Wisconsin, came to invent the modern notion of a national park for the recreation of future generations. His initial inspiration was Yosemite Valley, deep in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, where he was sought out by the US President, Theodore Roosevelt, who was persuaded on a characteristic Muir camping trip that such an uplifting place and its rich ecology should be preserved in perpetuity for the nation.

Anticipating the modern concept of biophilia our need for regular contact between our inner nature with the outer nature around us Muirs opening sentence continued with the idea that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life. Muirs suggestion that the fountains of our own lives need to be in contact with the self-renewing cycles of life in wild landscapes led him to be recognised as the founder of the American conservation movement. His establishment of the Sierra Club still to this day a vigorous local and national conservation organisation in the US arose because Muir understood the importance of local people holding government to account through membership of a national environmental movement. Muir knew that national policies would be needed if the balance between the economic usefulness of timber and rivers was to be controlled. By the end of Our National Parks Muirs tone had changed. Any fool can destroy trees, he declared in full preaching mode. God has cared for these trees but he cannot save them from fools only Uncle Sam can do that.

Actually, it was Muirs ecological knowledge, gained by close observation, by scientific experiment and by always reflecting upon the larger forces at work in nature, that resulted in insights ahead of their time, like the idea that unregulated clear cutting of timber reduced the usefulness of those irrigating rivers as fountains of life. At a time just before the notion of Oekology was being proposed, Muir wrote that, When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe. And it is in such unassuming, seductively approachable prose that Muir explored his vision of nature and our relationship with it. It was as a popular writer of newspaper and journal articles that Muir gained his following as a writer. Late in life he began crafting these little lyrical discoveries into the inspirational books that speak so clearly to our heightened environmental awareness today.

In many respects Our National Parks was the most important book that John Muir wrote. Only the second of the five books he published in his lifetime, it was certainly the bestselling book and the most influential that he saw into print. It is also notable in demonstrating the extraordinary range of his writing in the service of the remaining wild lands of the West at a time when the population of America was drifting towards the growing cities and in danger of neglecting their inner need for contact with nature. Muirs tone can shift in this book from seductive persuasion, to charming details of creatures, flora and landscapes, to scientific information, to trail guide, to religious uplift, to a final political speech of startling ferocity.

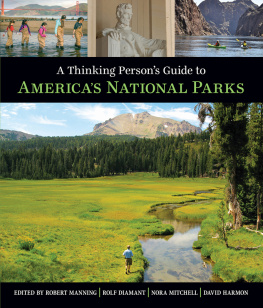

If the idea of national parks is popularly considered as Americas gift to the world and John Muir is thought of as the first person to fully articulate that idea, this book is where he makes his strongest case for national parks as human resources for recreation and the preservation of wild ecosystems on a large scale. The potential conflict between these aims in terms of access for the public compromising wilderness preservation would be a continual matter of fierce debate right up to today. But it is necessary to understand that neither of these aims, never mind their combination in a coherent policy, was being advocated at the time of the publication of this book in 1901. It is true that Yellowstone National Park was the first to gain this title in 1872, although the term public park was used in the enabling act itself which was more concerned with forestalling the commercial exploitation of its geysers and thermal springs. Similarly, Muirs chapter on The Sequoia and General Grant National Parks refers to small areas of parks around a few remarkable giant redwood trees that were to be protected from the rapacious lumbermen. This book not only makes the case for Yosemite Valley to be taken back from the state of California into national ownership as part of a concept of a large and complete Yosemite National Park, which had been created in legislation of 1892, but also advocates a system of national parks that would represent the distinctive ancient landscapes of an American feeling the lack of a European depth of history. John Muir presented the creators grand living land-art as the pre-classical heritage of Americans that outshone European manmade temples.

But first Muir had to get people engaged with what they should be voting to protect. Our National Parks begins by telling Americans that they are already getting there and that they were accepting these wild landscapes as their natural home: Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilised people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life. Muir cunningly does not deny the needs of the lumberman and the farmer that can be served by protected parks of wildness, but emphatically asserts their necessity for public health where people can mix and enrich their own little ongoings with those of nature, and get rid of rust and disease. Significant for international readers whose wild lands might not be on an American scale, Muir says that wildness is a necessity, and not wilderness as is often misquoted by people who should know better.

In the original preface to the book Muir said that he wanted to show the all-embracing usefulness of our wild mountain forest reservations and parks so that people visited and so that at length their preservation and right use might be made sure. And right use for Muir included spiritual renewal which he describes most clearly at the end of the Yellowstone chapter where he thinks of the substantial forms of flesh and wood, rock and water, air and sunshine as giving access to a sense of a truly substantial, spiritual world [] to learn that here is heaven. This is now sometimes called the re-enchantment of material nature, and for Muir this was informed by his scientific curiosity, rather than at odds with it, as he looked into the tertiary volumes of the grand geological library of the park. Indeed, Muir wrote Our National Parks after having completed a national scientific survey of American forests as part of a commission for President Roosevelt. Muirs focus in much of this book on forest reserves was a political strategy in a continuing debate about just how much timber could be taken from the nations forests under the policy of right use. One of Muirs fellow commissioners, Gifford Pinchot, had recently been put in charge of the management of national forest reserves and Muirs opinion of his notion of right use lies behind much of the agenda of this book: his giving way like snow in thaw to the sheep owners and political agents of forest robbers is mighty discouraging.