Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books explore human relationships with natural environments in all their variety and complexity. They seek to cast new light on the ways that natural systems affect human communities, the ways that people affect the environments of which they are a part, and the ways that different cultural conceptions of nature profoundly shape our sense of the world around us. A complete listing of the books in the series appears at the end of this book.

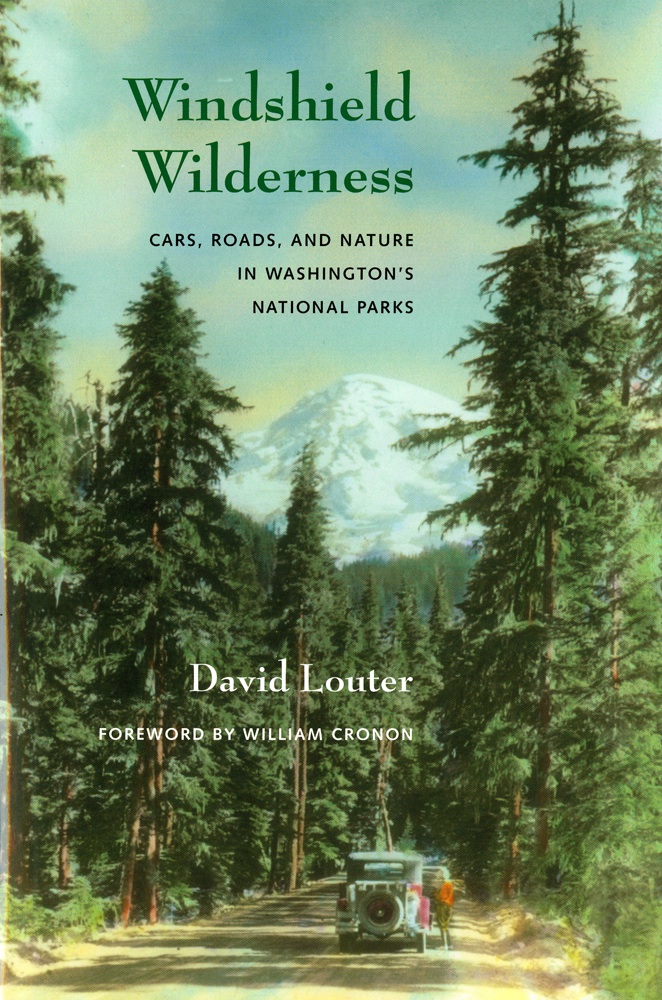

WINDSHIELD WILDERNESS

Cars, Roads, and Nature in Washington's National Parks

DAVID LOUTER

Foreword by William Cronon

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

Seattle and London

Windshield Wilderness: Cars, Roads, and Nature in Washington's National Parks is published with the assistance of a grant from the Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books Endowment, established by the Weyerhaeuser Company Foundation, members of the Weyerhaeuser family, and Janet and Jack Creighton.

Copyright 2006 by University of Washington Press

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Pamela Canell

12 11 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press

PO Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98145

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Louter, David.

Windshield wilderness : cars, roads, and nature in Washington's national parks / David Louter; foreword by William Cronon.

p. cm. (Weyerhaeuser environmental books)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-295-98606-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-295-98984-6 (Electronic)

1. National parks and reservesPublic useWashington (State) 2. National parks and reservesWashington (State)Management. 3. AutomobilesEnvironmental aspectsWashington (State) 4. RoadsEnvironmental aspectsWashington (State) I. Title. II. Weyerhaeuser environmental book.

SB486.P83l68 2006 333.783dc22 2006004335

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and 90 percent recycled from at least 50 percent post-consumer waste. It meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

For Rebekah, Arendje, and Mara

MAPS

FOREWORD

Look to the Wilderness

WILLIAM CRONON

Lucky indeed is the book with a title so perfect that it manages to convey with just two strikingly unexpected and arresting words the core of the argument that its author wishes to make to readers. David Louter's Windshield Wilderness: Cars, Roads, and Nature in Washington's National Parks is such a book. What it has to say about the changing role of automobiles in the twentieth-century American experience of wild nature will be of interest to anyone who cares not just about the three parks whose histories it exploresMount Rainier, Olympic, and North Cascadesbut parks and wild places all across the nation. Let me explain why.

Many who encounter the phrase windshield wilderness for the first time may experience it as a contradiction in terms, an oxymoronic play on words that, however clever, succeeds in calling attention to itself only by being perversely nonsensical. As we typically understand it in the early twenty-first century, wilderness is a large tract of land distinguished above all else by the dominance of nonhuman nature and the relative absence of human influence. Furthermore, as the environmental historian Paul Sutter has brilliantly argued in his book Driven Wild: How the Fight against Automobiles Launched the Modern Wilderness Movement (published in the Weyerhaeuser series in 2002), the struggle to protect wilderness in the United States has historically had as one of its most vital objects the protection of wild places from the incursions of roads and automobiles.

Ever since the passage of the much-celebrated Wilderness Act of 1964, wilderness in this country has had at the core of its legal definition the concept of roadlessness. In a key section declaring the Prohibition of Certain

If all these cars, boats, trucks, and planes were to be prevented from transgressing the legal boundaries of wilderness, then surely, by definition, no wilderness should have anything whatsoever to do with windshields. Yet here we have an author who proposes to write a book about wilderness as seen through the windows of an automobile. What on earth could this wrongheaded person possibly be up to?

The answer is that David Louter, who works as a historian for the National Park Service in the Pacific Northwest, has used the three great national parks of the state of Washington to produce an invaluable case study of the radical shifts in attitudes toward automobiles that affected most national parks in the United States over the course of the twentieth century. At the very beginning, national parks like Yellowstone and Yosemite were promoted by the railroads in an effort to increase western passenger traffic and ticket sales. As a result, most tourists reached them via train. Only in the second decade of the twentieth century did visitors start to arrive in automobiles, but from that point onward, car-based tourism grew steadily and became ever more important. When the National Park Service was created in 1916 as the agency with primary responsibility for managing the parks, its first and second directors, Stephen Mather and Horace Albright, put enormous energy into promoting the parks and encouraging as many people as possible to visit them. When this impulse toward maximum accessibility was coupled with the cheap labor for road construction made available by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the New Deal, the result was a large-scale proliferation of highways leading to and through the national parks. These included some that to this day remain among the most spectacular anywhere in the UnitedStates: Going to the Sun Highway in Glacier National Park, the ZionMount Carmel Highway in Zion, the Blue Ridge Parkway in Shenandoah, Trail Ridge Road in Rocky Mountain National Park, and so on.

It was precisely these new roads in the 1930s that led a group of activists who most valued the backcountry experience of primitive nature to conclude that the National Park Service was itself becoming one of the greatest threats to wilderness in the United States. This is Paul Sutter's argument: that the founders of the Wilderness Society, and those who worked to pass what would eventually become the 1964 Wilderness Act, were appalled by the nationwide decline in roadless places and so began working to protect those places from reenacting the pernicious example of national parks that were entirely too accessible to cars. For these activists, it was patently obvious that windshields were not only the wrong way to experience wilderness, but in fact represented a deep threat to the wilderness experience itself.

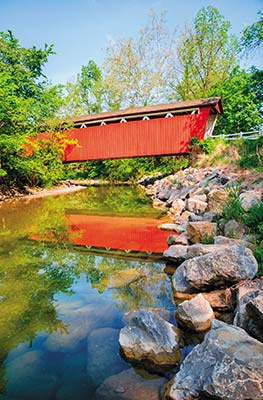

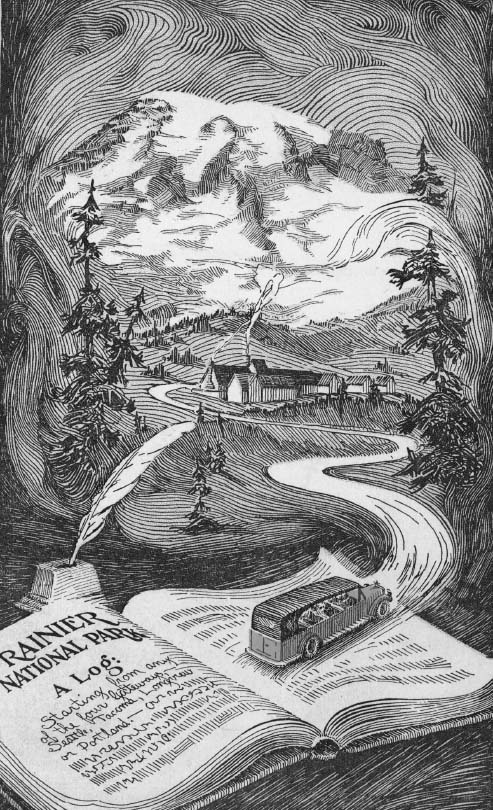

In Windshield Wilderness, David Louter's first case study is Mount Rainier National Park, founded in 1899. Not least because Rainier was unusually accessible to the adjacent metropolitan populations of Seattle and Tacoma, its managers were among the first in the nation to push roads deep into the heart of their park, so that tourists could ride high up the mountainside without ever leaving the comfort of their automobiles. By 1910, the first segment of construction was completed on a road that was intended to completely encircle the mountain, enabling visitors to drive to the very edge of the glaciers.