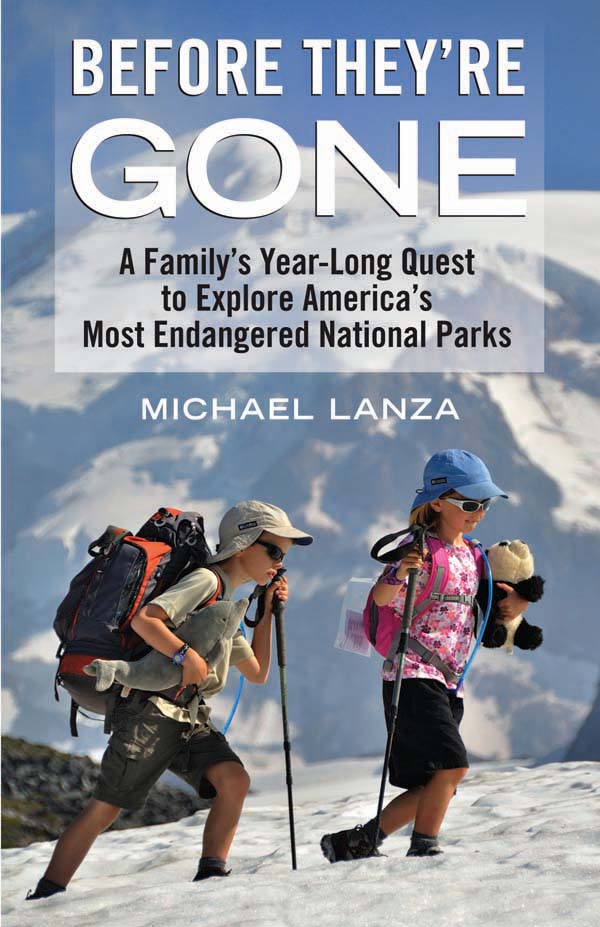

Before Theyre Gone

A Familys Year-Long Quest to Explore Americas Most Endangered National Parks

Michael Lanza

Beacon Press

Boston

To my parents, for the gift of unconditional love.

To Penny, for understanding.

And to Nate and Alex, for teaching me.

The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed.

Albert Einstein

Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. Its not.

Dr. Seuss, from The Lorax

CONTENTS

Prologue: Inspiration

Summer and Fall 2009

The wind above ten thousand feet sweeps down from the cliffs, the August snowfields, and the jagged mountaintops high above us in gusts powerful enough to push around two hikers who each weigh less than my loaded backpack. The trail zigzags relentlessly upward, crossing a tilted sea of rocks that are embarked on an inexorable journey downhill, many of them advancing a little farther under our footsteps. The alpine sun bears down on these shadeless heights in Wyomings Teton Range, and the air grows thin.

I check my two undersized companions for hints of fatigue, hunger, or unhappinessa slowing pace, a faraway look, complaining. But none of these discomforts that would unhinge most adults appears to disturb my kids in the least.

Ahead of me walks Nate, eight years old and already a seasoned backpacker with several trips under his belt going back to age fiveor to infancy, if you count the times he rode in a backpack. He absently swings Flipper, the stuffed dolphin in his hand, while discoursing, in elaborate detail and without pause, on his latest ideas for inventions: personal rockets powered by renewable energy and a device to make clouds shed more snow in winterfor skiing, of course.

Alex, our six-year-old daughter out on her most ambitious hike to dateeighteen miles over three days, including yesterdays climb of nearly 3,000 feet, and the 10,700-foot pass still above us, Paintbrush Divideoccasionally speaks to her stuffed dog, Swiss. Mostly, though, she passes the time playing our number game, in which she and I try to guess what number were each thinking of. She can play this game for hours without tiring of it. Im getting a little tired of it. But it keeps her moving happily, if ploddingly forward, so I keep playing.

In everyday life, with its distractions and obligations, there exists no corollary for this time with them. In civilization, we race from one task to the next and fill our leisure time with programmed entertainment or the electronics and toys weve amassed. But in the backcountry, theres no daily planner. Beyond the needs of setting up camp and preparing food, theres nothing to demand our time except one another and the calmingly unscheduled live theater of nature. Only out here do I spend hours a day just talking to my wife and kids.

Since we started hiking yesterday morning, other backpackers have stopped and stared at our kids, asking their ages. Alex and Nate have probably noticed that weve seen only a few other kids out here. But they have no grasp of the anomaly of their own presence. It would mean nothing to them to hear that I was past thirty when I first saw these mountains and walked this trail; they are Westerners, but I was a child of the East who discovered the West as an adult. They dont yet appreciate that they are experiencing one of Americas most beloved landscapes more intimately than the vast majority of their countrymen ever will.

But thats the problem with mature perspective: you dont acquire it until long after it first would have been useful.

Nate and Alex pause on an outcropping of broken rock. The land before us displays a sort of topographical bipolarityplunging into a canyon bottom beyond our line of sight, then just as abruptly vaulting up into the impregnable fortress of rock walls and buttresses composing Mount Moran. This is something like my fifteenth trip in the Tetons, and yet familiarity has not dulled my awe of them. But my kids are not gushing over the scenery; theyre pointing with amazement at a small tarn a couple hundred feet below us, still mostly ice-covered in mid-August. I know they ache to stand on its shore hurling stones to smash the ice.

As we near the pass, the wind musters even more force and the rocky, narrow trail clings to the face of a crumbling cliff. My wife, Penny, and I, with our longtime friend Bill Mistretta, hover close to our undaunted kids, herding them to the inside of the trail, away from the precipice. And we try to exude calm, as if were just crossing the street to their elementary school.

Although preoccupied with my childrens safety, I cannot help but noticesimilar to what other Teton habitus have observedthat these mountains are less white in summer now than when I first backpacked and climbed here almost two decades ago. The planet grows steadily warmer. As in most mountain ranges, less of winters snowfall survives through the summer here. The reverberations of this change echo around the world. But unlike a true echo, this one does not cease and its volume keeps rising.

Later that afternoon, we find a campsite by the swift creek pouring over steplike ledges in the North Fork of Cascade Canyon. I assume Alex and Nate will be exhausted from todays efforts. But they spend most of the hours until dark tirelessly tossing sticks into the foaming current or using the sticks to pound rocks, seeing serious purpose in missions that exist only in their imaginations. I see purpose in their activities, too. But I think the end product is imagination, and it all seems to begin with some ancient hardwiring in us to make tools.

Walking in these mountains again stirs in me an upwelling of memories. Mental images glide like creek waters around the fixed midstream rocks anchoring me in the present: my kids. And yet, recollections remain viscerally vivid, retrieving sensations across years.

On a vertiginous wall a thousand feet above the cracked, wizened complexion of a glacier, my hands clutched rock that felt like a wrought-iron fence on a November morning, and I nervously watched clouds boiling up around pointy granite fingers overhead, hoping they wouldnt coalesce into thunderheads before we finished the climb. My skis whispered secrets knowable only to my two companions and me as we glided over snow that bore no evidence of other humans, and in every direction white mountains lunged for heaven and canyons collapsed into unseen depths. Water offered gentle resistance to the pull of my paddle tugging our canoe across a sun-warmed lake, its far shore sprouting a row of peaks resembling cathedrals. Leg muscles thickened and feet throbbed at the end of a twenty-mile day hike or a six-thousand-foot scramble, as a friend and I clinked bottles of beer and watched the setting sun perform the impossible, transforming water vapor impaled upon mountaintops into flames.

Invariably, people occupy these memories, imbuing them with the broadest dimension: emotion.

Powerful landscapes like the Tetons will manhandle your psyche; they can make you wonder what the hell youve been doing all these years, for which you wont have a satisfying answer. But overlaying a complex tapestry of personal history on a place of aching natural beauty animates it. In time, the place insinuates itself into a major role in the story of your life.