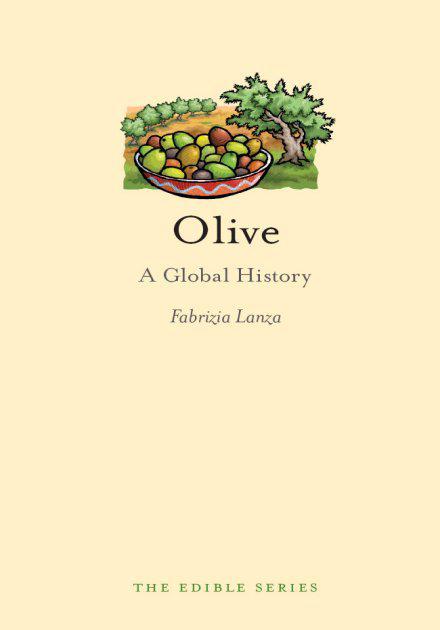

OLIVE

Edible

Series Editor: Andrew F. Smith

EDIBLE is a revolutionary new series of books dedicated to food and drink that explores the rich history of cuisine. Each book reveals the global history and culture of one type of food or beverage.

Already published

Apple Erika Janik | Ice Cream Laura B. Weiss |

Bread William Rubel | Lobster Elisabeth Townsend |

Cake Nicola Humble | Milk Hannah Velten |

Caviar Nichola Fletcher | Pancake Ken Albala |

Champagne Becky Sue Epstein | Pie Janet Clarkson |

Cheese Andrew Dalby | Pizza Carol Helstosky |

Chocolate Sarah Moss and | Potato Andrew F. Smith |

Alexander Badenoch | Sandwich Bee Wilson |

Curry Colleen Taylor Sen | Soup Janet Clarkson |

Dates Nawal Nasrallah | Spices Fred Czarra |

Hamburger Andrew F. Smith | Tea Helen Saberi |

Hot Dog Bruce Kraig | Whiskey Kevin R. Kosar |

Olive

A Global History

Fabrizia Lanza

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC V DX , UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2011

Copyright Fabrizia Lanza 2011

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior

permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by C&C Offset Printing Co. Ltd

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Lanza, Fabrizia

Olive: a global history. (Edible)

1. Olive. 2. Olive History.

3 . Cooking (Olives)

4. Olive Folklore.

1. Title 11. Series

641.3 463-DC22

eISBN 9781861899729

Contents

Introduction

The olives history is almost as ancient as that of humanity itself. An olive tree does not reach its full productivity for 35 years and it is a plant that can endure for centuries. Who was the first person patient enough to wait those three decades? Whoever he or she was, we know that the olive has been growing alongside human beings from time immemorial. It lives in our literature, it is part of our symbolism, it lights our prayers and it enriches both our culture and our diet.

The wild species of the plant seems to have been discovered at least 10,000 years BCE , and the domesticated version appeared some 4,000 years ago. It is a story that goes back at least to the beginnings of agriculture, when human beings first settled down and began to cultivate the earth and harvest its fruits. To trace in just one brief volume the long, long story of the olive, its symbolic significance and the technical skills that had to be mastered in order to press the oil and cure the olives, is thus to undertake a voyage 6,000 years long. It is an entertaining voyage, during which an almost infinite number of tales and legends emerge, a multitude of customs and traditions that belong to many different places and civilizations. These cultures may be far away from our own in time and place but they all attributed to the olive a high, even regal status, a value well beyond the plants dietary or cosmetic uses.

Homer, Virgil, Cato, Pliny, Aristophanes, Dante, Shakespeare, Frdric Mistral, Van Gogh, Calvino: many poets, scientists, artists and historians have admired the olive tree, granting it the status of a genuine icon of the Western world. To be born under an olive tree was a mark of divine ancestry: the twins Artemis and Apollo as well as Romulus and Remus, descended from the gods, were born under an olive tree. Olive wood, signalling endurance and quality, often appears during Odysseus endless travels: his bed is carved from an ancient olive tree, the stick thrust into the Cyclops eye is made of olive wood, and so is the handle of the axe with which he builds his boat.

From time immemorial, anointing oneself with oil has been the preferred way to approach the hereafter. Unguents, mixtures of oils and spices, were sacred to the Babylonians and to the prophets of the Bible; they were essential during the burial of ancient Greek athletes and warriors; and they played an integral role in the Christian sacraments. In the Middle Ages, holy oil, precious and deeply sacred, was said to flow directly from the bones of Christian martyrs. Almost as powerful in modern times is the way imported olive oil subtly conveyed a sense of identity to European immigrants in the United States, satisfying, along with their appetites for flavours from home, their nostalgia and other intangible desires.

An overview of these six millennia of history must obviously begin with a brief excursus on the olive tree itself, from pre-history to modern times a multiform and complicated story of the ships that sailed the waves of the Mediterranean back and forth, first from East to West, and slowly conquered all of Europe. The second chapter traces the symbolic role the olive and its oil have always played, from rituals in Egyptian and Etruscan tombs, to the Christian sacraments, to the rituals celebrated in the past century in Provence and central Italy during the olive harvest. A third chapter is dedicated to the history of oil extraction from the earliest mortars in which the olives were crushed, to primitive presses, often of industrial dimensions even in ancient times, to the more sophisticated machines of the nineteenth century. Curiously enough, the knowledge and skills related to olive cultivation, harvest and pressing that were accumulated by the ancient Romans and lost for centuries during the Middle Ages reemerged, like an underground spring, in modern times. In the fourth chapter I write about the olives migration to the New World with the arrival of the Spanish empire in South America. Once the olive had established itself in the fertile soils of California, it was largely the immigrants from Mediterranean countries who took charge of it, delighted to have this memory of home in a far-away land. The book concludes with some questions about the Mediterranean Diet, those dietary recommendations that, beginning in the 1950s, brought with them a new idea about the beneficial effects of olive oil. Could it be that behind this newfound passion for olive oil there are motivations that go far beyond the dietetic and medical arguments made by scientists, doctors and dietary experts? Are there more profound reasons why we favour olive oil? These are tantalizing questions.

There are many, many recipes made with olive oil, somewhat fewer that employ the olive fruit. In giving recipes Ive taken a thematic approach, offering cross-country comparisons of how olive oil becomes the base for a sauce, for example: to make aioli in Provence, or pesto in Liguria. Bread dipped in oil is a basic element of the Mediterranean Diet, whether it is called bruschetta in Rome, brissa in Nice or fettunta in Tuscany. Finally, olive oil is still the preferred fat in some traditional Southern European sweets and desserts, a custom that gives these dishes a decidedly Mediterranean texture and a flavour that is far from French-style patisserie made with butter.

Next page