CONTENTS

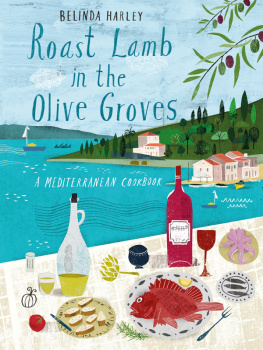

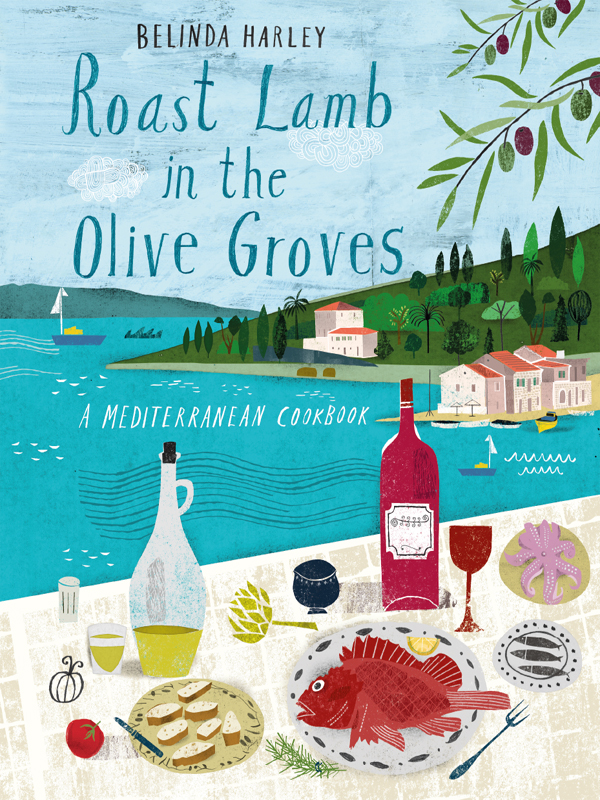

It is Easter Sunday morning. Across the island, church bells are ringing and so many families are outside in the bright sunshine, their children watching intently as the Easter lamb is turned on a spit, so that as you walk along the old stone donkey paths that lead from village to village, the scent of roast lamb wafts to you through the olive groves

If you look on a small-scale map of the Ionian sea, the little island of Paxos and its even tinier sibling, Antipaxos, are sometimes omitted entirely. It is as if they have simply been left to the imagination

It could be said that the Paxiots have been blessed, even by their misfortunes Scattered in the sea below the heel of Italy, they were at a strategic point in the Mediterranean, like their bigger neighbour Corfu. They were prey to serial occupation down the centuries, as invaders took possession and were ousted in turn. But they came bearing gifts: the Romans built magnificent sterna, cisterns to collect water; the Venetians spent four centuries bribing the locals to plant thousands of olive trees. These changed the islands landscape entirely, and yield some of the best, grass-green olive oil in the world.

History is alive in the kitchen. Venetians brought risotto, pasta and an Italian sense of style; the hated Turks awakened the Paxiots palates to spices; Napoleons favourite bchamel besamel to the Paxiots adorns todays moussaka. And when Paxiots have had a hard night of celebration, they clear their heads with tzintzibira, English ginger beer, from a recipe left behind by the Victorians. The Paxiots adopted the things they liked and infused them, like powerful aromatics, into basic Greek cooking. Recently, they have been showing an unexpected interest in curries

This is not a traditional Greek cookbook. I am not Greek and one would need the knowledge handed down over centuries, through families, that is the hallmark and inheritance of a native Greek cook. I hope this book does something different: it records the ancient ways; it shows you how to cook in their style, and be inspired by their natural ingredients to make culinary voyages of your own.

I owe this book to Spiros Taxidi, who showed me the food of the island: he is both a mentor and a brother. He and his fellow Paxiots show how it is possible to live simply, and gloriously, on what grows each season. They remind us of something that, deep down, we always knew: that food is better, when it is truthful.

Our word diet comes from the ancient Greek word dieta. It means way of life: and this is a way of life based on fruit, vegetables, natural grains and pulses full of fibre; freshly made cheeses and yoghurts; fish, poultry and occasionally a little red meat. It is a peasant diet in that it is just the sort of Mediterranean diet that nutritionists now recognise as one of the healthiest.

Food here is a way of life and the local people still follow the old ways. They cook ancient recipes: simple dishes handed down the generations, until they become instinctive in which good ingredients are allowed to speak for themselves.

On Paxos, cooks still rely, just as they did in ancient times, on the natural flavour of what they grow. They prefer extra-virgin olive oil that has been cold-pressed, rather than industrially produced. They make cheeses from the milk of their own sheep and goats. They are proud of their foraging skills underwater, in collecting shellfish and in fishing. Meat and poultry comes from animals that are grazed on hillsides that have never known pesticides. These Paxiots use herbs and spices astutely in their dishes, with an intuitive, exquisite judgement.

Finally, the reason this food is so glorious is something to do with the Paxiots themselves. They enter into the spirit of religious festivals, saints days, weddings and family occasions with a seriousness of community purpose and childlike joy.

They believe that life is to be celebrated: and it should be celebrated with food.

MY FIRST TASTE

Many years ago, a fisherman on Corfu with a battered wooden caique agreed to take us to see the nearby island of Paxos; he said it would take five or six hours to get there. At noon, the heat became brutal. The sea was glassy and eerily flat. Suddenly we heard a cacophony, as of knives and forks beating on a drum: like tinnitus, it was coming from the island. Cicadas. The whole of Paxos was throbbing with them.

Otherwise, the island seemed to be dead to the world. We landed at a tiny fishing village, where the lanes were no more than narrow footpaths between closed, shuttered buildings. Even the cats had hidden from the heat, curled up deftly in the shade. Our Corfiot fisherman banged a closed front door. My cousin, he explained. A generous moustache and a stubbled chin appeared at the door. Then another cousin. Then another. Rough slapping of hands, proffering of cigarettes, rousing the women of the house. We were too many for the tiny kitchen, so the family table and chairs were simply moved outside to receive us: the dining room had become an informal street taverna.

It is only vegetables, said the fisherman apologetically, aware that tourists expected meat. Oh, those vegetables great glistening discs of tomato, with flakes of salt and basil; pale jade hearts of artichoke; woody, dark green spinach; rustic bread, with salty-sweet black olives; and a plate of cool tzatziki, which hummed with garlic. I have never forgotten the taste.

Riding pillion on the cousins Vespas, we bumped over tracks through the olive groves to an even smaller fishing village: Loggos. There was no-one about. A small white jetty stretched like a finger into the sea. We dived into cold turquoise water, then lay like lizards on the rocks to dry our bodies. At that far-off time, I had no idea how often I would return to that jetty, to moor a small boat and watch the world go by; to sit on the nosey bench with the old ladies who sat exchanging the village news

So like the helidonia, the swallows, who make a journey of thousands of miles from Africa to build their nests on the sheer Eremitis cliffs, swooping and diving in acrobatics of exhilaration overhead, I too became a migrant. And each time I returned, I appreciated the food of Paxos and its deceptive simplicity, more. When offered a Michelin-starred menu in London, why did I feel a pang of disappointment, like a child given expensive Christmas presents who suddenly cries out for a much-loved familiar toy? The words fine dining suddenly sounded artificial, wrong; I wanted food.

I am conscious of irony in writing this book in celebration of the Greek way of life, at a time when the Greek people are in trouble. The financial situation has dragged the country into a vortex of poverty; its people, burdened by national debt, leeched by corruption, are near despair.