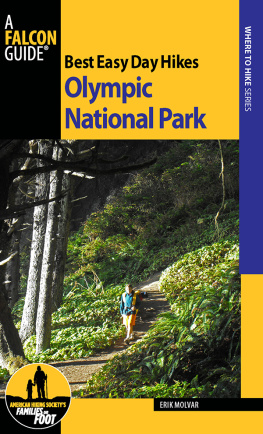

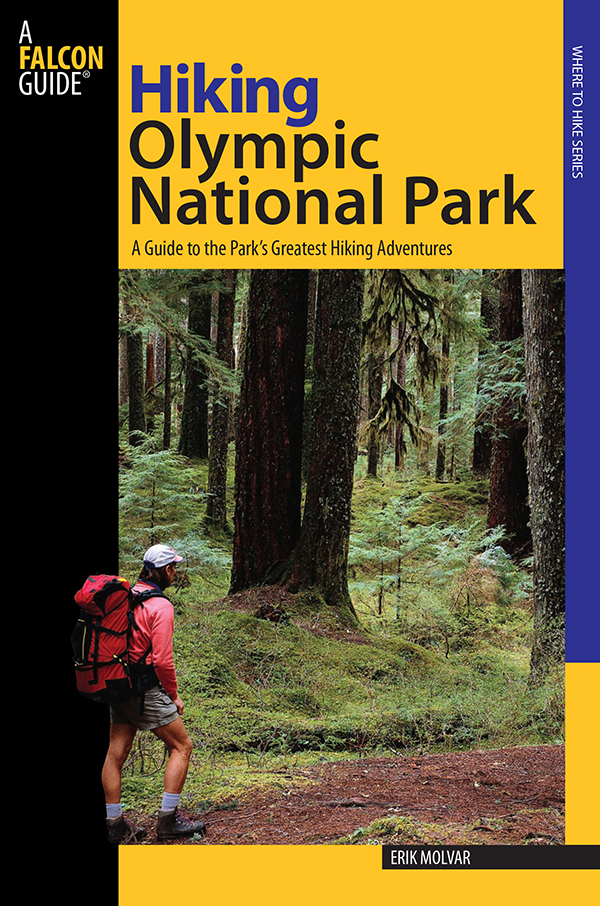

Hiking Olympic National Park

A Guide to the Parks Greatest Hiking Adventures

Second Edition

Erik Molvar

Copyright 1997, 2008 Morris Book Publishing, LLC.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to The Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford CT 06437.

Falcon and FalconGuides are registered trademarks of Morris Book Publishing, LLC.

Text design by Nancy Freeborn

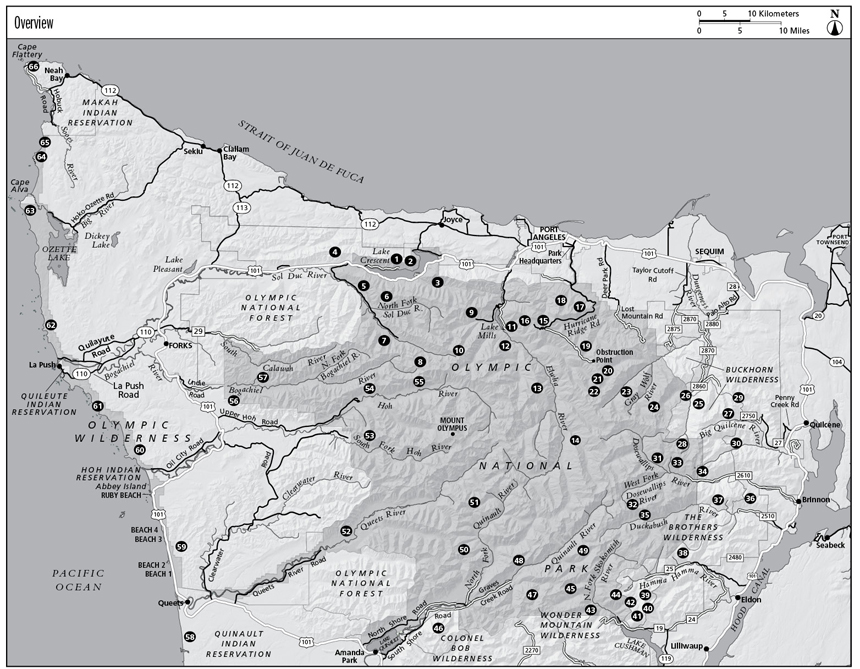

Maps created by Daniel Lloyd Morris Book Publishing, LLC.

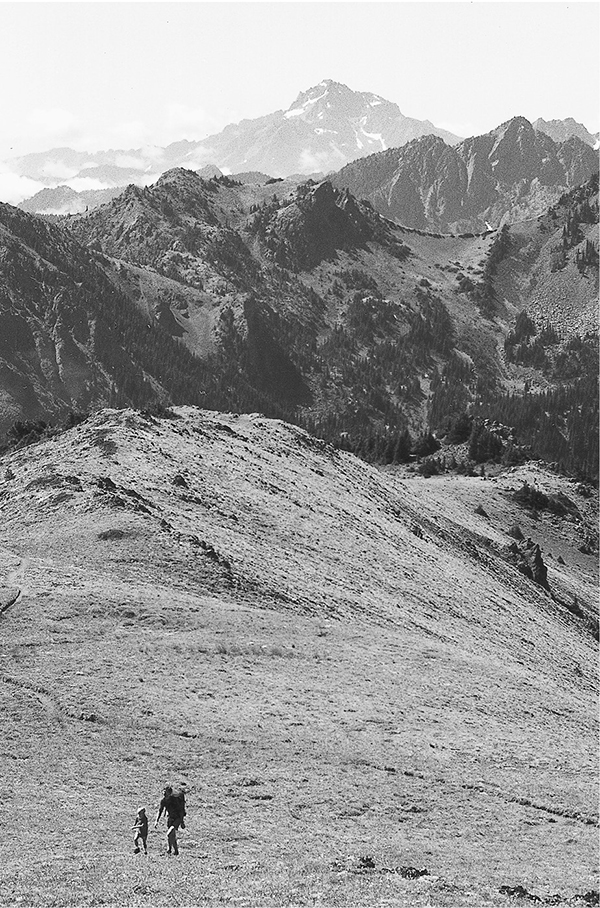

Interior photos by Erik Molvar.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Molvar, Erik.

Hiking Olympic National Park : a guide to the national parks greatest

hiking adventures / Erik Molvar. -- 2nd ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7627-9742-4

1. Hiking--Washington (State)--Olympic National Park--Guidebooks. 2.

Trails--Washington (State)--Olympic National Park--Guidebooks. 3.

Olympic National Park (Wash.)--Guidebooks. I. Title.

GV199.42.W22O496 2008

796.510979798--dc22

2007049925

The author and The Globe Pequot Press assume no liability for accidents happening to, or injuries sustained by, readers who engage in the activities described in this book.

Contents

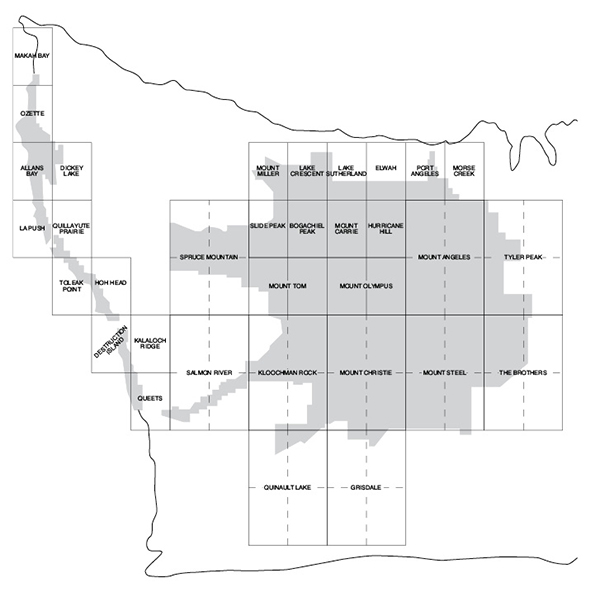

USGS Quad Map

Acknowledgments

During the course of writing this book, I have received valuable assistance from a variety of agency personnel and local residents, only a few of whom are mentioned here. Ruth Scott served as a primary liaison throughout the project and has been a wellspring of information. Bill Baccus was a wizard at procuring and reviving walking wheels. Tom Shindler of Custom Correct Maps provided additional distance data and valuable information on the Additional Trails. Nelsa Buckingham shared with me her veritable treasure trove of botanical information. Geological information presented here relies heavily on the works of R. W. Tabor and W. M. Cady. Bruce Moorhead, Susan Schultz, Chuck McDonnell, Dave Conca, Kirstie Ray, Bryan Bell, Jerry Freilich, Hank Warren, Jim Halvorson, Molly Erickson, Susan Graham, and the entire revegetation crew provided supplementary information and advice. A special thanks to Pat Pratt at the Camera Corner for the excellent darkroom work and for keeping my camera and soul together during my research.

Introduction

Olympic National Park encompasses the glacier-clad spires that crown the peninsula as well as the wild and windswept beaches of the Pacific coast. It shelters a rare temperate rain forest ecosystem found only in a few pockets elsewhere in the world. The Olympic Mountains have been isolated from other ranges for millennia, and this isolation has led to the development of a unique alpine community of plants and animals. Some of these are found nowhere else on Earth. This bountiful ecosystem provides a refuge where weary city dwellers can seek inspiration in the midst of natures majesty.

The uniqueness of this area was recognized in the late 1800s, when the region was set aside as a forest reserve. President Theodore Roosevelt created a national monument within the reserve in 1909, in part to protect the forest subspecies of elk that now bears his family name. National park status came in 1937, and the additional protection of wilderness status for the remote parts of the park was conferred in 1984. At the same time, five adjoining blocks of national forest land were declared wilderness, protecting 91,000 additional acres of this diverse and beautiful ecosystem. The park and its surroundings have been internationally recognized as a biosphere reserve and a world heritage site.

An extensive network of trails provides access into the most remote corners of the mountains, and a well-planned series of wilderness routes allows hikers to take in most of the Olympic coastline. There are 581 miles of maintained trails within the national park, and hundreds more on the adjoining national forest lands. This book covers all of the maintained trails and designated routes within the park and the adjacent wilderness areas. These trails provide a full spectrum of recreation opportunities, from short strolls to extended journeys that penetrate to the heart of the mountains.

The Making of the Mountains

The Olympic Peninsula appears to be attached to the northwest corner of the continent as an afterthought. In geological terms, this impression is absolutely correct. The peninsula is actually the eastern end of the Juan de Fuca Plate, a small terrane that collided with the much larger continental plate millions of years ago. The resulting folding and faulting of the earths crust produced the mountains we see today.

These mountains had their genesis on the bottom of the ocean. Cracks in the sea floor allowed molten magma to well up into the water, forming a deep-sea range of volcanoes. These seamounts were already quite old when the Juan de Fuca Plate approached the rim of North America. As the plates collided, enormous pressures pushed the seamounts upward. The Juan de Fuca Plate began to dive underneath the margin of the continent, but the seamounts were wedged against the continental plate, and movement ground to a halt. Beds of sedimentary and metamorphic rock piled up behind the seamounts like boxcars behind a derailed steam engine, with deep faults between them (see Figure 1). The ancient undersea lava beds now form a horseshoe of crags that stretches from Lake Crescent through Mount Constance and The Brothers and extends southwest as far as Lake Quinault. This pillow basalt is resistant to erosion, and as a result many of the highest peaks in the range occur within this narrow belt. The interior ranges are a mix of sandstone, shale, and slate. The border between these two formations is a zone of heavy faulting where hot springs well up through the earths crust.

The newly created mound of high country was soon dissected by streams, which carved a system of shallow valleys in a radial pattern. With the coming of the ice ages, these valleys filled with glaciers, which deepened them into the U-shaped clefts that we see today. At the same time, an enormous Cordilleran ice sheet filled the Puget Sound basin and lapped against the base of the Olympics like a great frozen sea. It dammed up the waterways, forming huge glacial lakes that extended far into the mountains. Lake Crescent and Lake Cushman are remnants of these glacial lakes, and granite erratics brought in by the ice sheet can be found in certain parts of the peninsula.