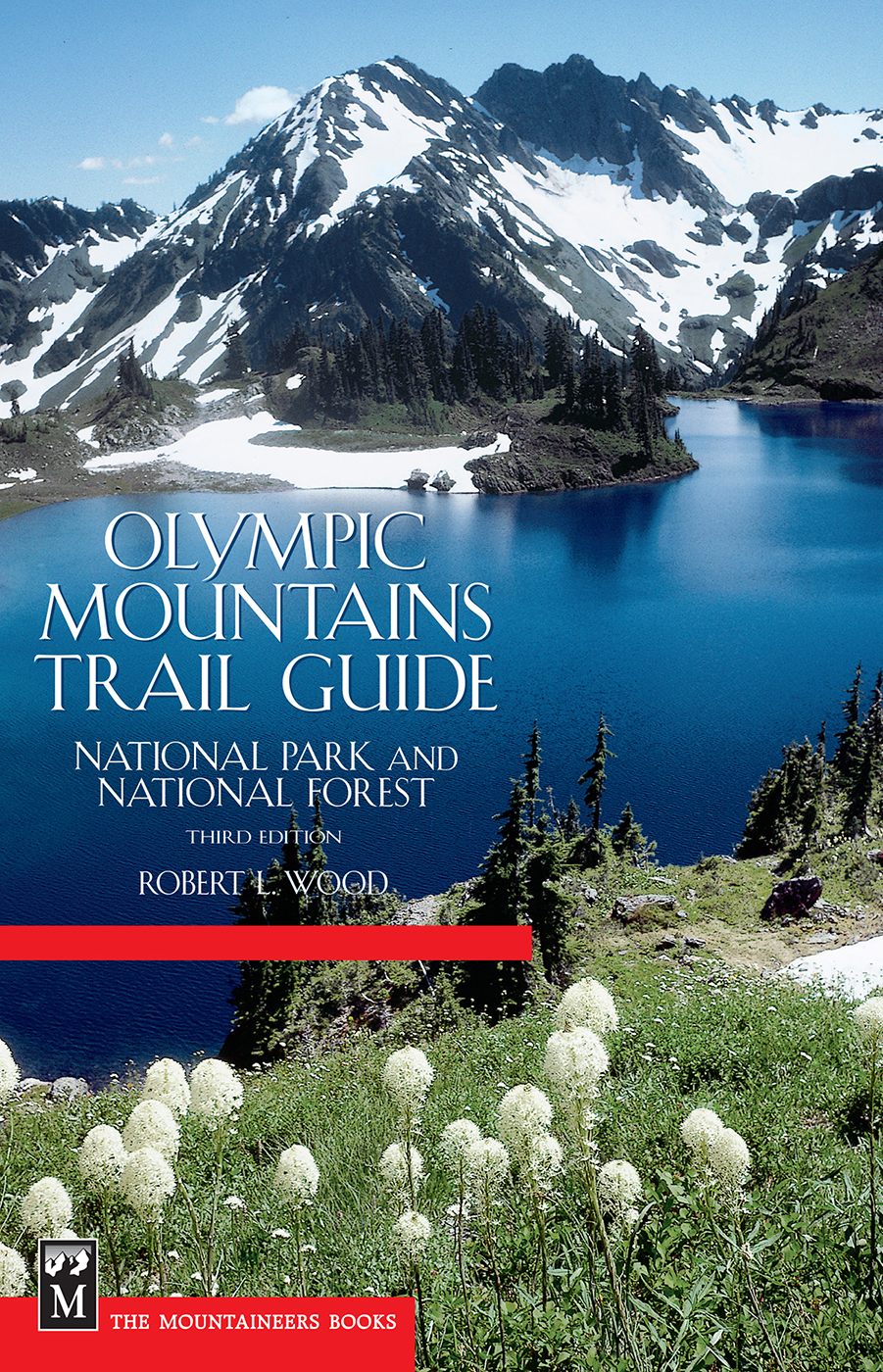

OLYMPIC MOUNTAINS TRAIL GUIDE

NATIONAL PARK AND NATIONAL FOREST

THIRD EDITION

DETAILED DESCRIPTIONS OF ALL CONSTRUCTED AND WAY TRAILS IN THE OLYMPIC MOUNTAINS, MAINTAINED AND NOT MAINTAINED

ROBERT L. WOOD

REVISED BY

TERRY WOOD

I keep telling myself that the beauty of hiking and climbing is discovery, pure and simple. How hard is the next hill, whats the trail really like from Low Divide to Elip Creek? Climbers have developed a system to rate and grade climbs, and they are now into a veritable foreign language about it all... Rather than demystify climbing it has bred unholy competition. Climbing magazines routinely diagram a pitch or climb with all sorts of little symbols. Its all become too clinical, techno-climbing. Are we going to publish scale side views of hikes, so you can visually see the ups and downs? No, leave that to me, the hiker, for those dark winter nights at home.

William E. Hoke, after a trek through the Olympic Mountains

Mount Olympus

Storm Damage

Each year winter storms produce flooding, rockslides, avalanches, washouts, and downed trees that impact trail accessibility and passability. To determine the most up-to-date conditions, readers are encouraged to either call the agency that manages a trail that interests them or review trail conditions on the agencys website.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

* An asterisk preceding the listing of a trail indicates that it is a wholly or partially abandoned trail or a way path with limited or no maintenance.

NORTH SLOPE

HAMMA HAMMA

145Big Creek Trail

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION

Like its predecessors in 1984 and 1991, this third edition of Olympic Mountains Trail Guide is intended to serve not only as a field guide to hiking the trails of the Olympic Mountains but also as a reference work to consult at home. Although written primarily for hikers and backpackers who are not well acquainted with the Olympics and are therefore seeking ideas about where and when to go, the book can be used by persons familiar with the region and also by armchair adventurers who desire to explore the country the easy wayby reading about it when lounging beside the fireplace on a cold winter evening. I have attempted to describe the roads and trails in helpful language; I have also endeavored to answer the questions invariably expressed by hikers or backpackers: Why go there? Why hike a particular trail?

Essentially, the book has been distilled from my intimate acquaintance with the Olympics during the last half-century. I do not know how many miles I have walked in these mountains, but they number in the thousands. I went on my first hike in 1948, and a year later made my initial backpacking trip. Since then I have hiked, backpacked, and climbed in the Olympics every year, during all seasons, and in all kinds of weather. I have often repeated trips a number of times because I find that hiking familiar trails is much like wearing a comfortable pair of old shoes.

I have also walked many milesoften alone, but usually with companionsbeyond the trails, traveling cross-country through forested valleys and canyons, along windswept ridges, and across pathless meadows. I have stood upon the summits of many of the higher peaks a number of times. During the period 195485, I participated in twenty-seven climbers expeditions to Mount Olympus, during which I ascended West Peak, its highest pinnacle, sixteen times. On several of these climbs I camped overnight on the summit of Five Fingers Peak (West Peaks slightly lower companion), and as far as I am concerned this experience was the ne plus ultra of my Olympic adventures.

Only in this way, I felt, could I really get to know the Olympics, and when writing about them capture the essence and feel of the country. I have attempted to include all the trails, both in the national park and the national forest, but I am not so nave as to contend that I have described every footpath created by man. Not long after the first edition appeared, a young man who prided himself on his knowledge of the high Olympics wailed in heartbroken dismay: Why, you dont even have the P J Lake Trail in your book! If I have overlooked others, I have not been made aware of them, and they would necessarily have to be either seldom-used way paths or perhaps fragments of long-abandoned trails that have vanished. Nearly all trails of consequence have been included in this book.

I have not, of course, walked every trail during all four seasons of the year; the descriptions therefore depict the country traversed as I observed it during particular seasons in certain years. But conditions vary from year to year, and from one season to another. Hikers are thus likely to note change, because it is inevitable and constant. Few things, if any, are truly permanent. Man-made features such as bridges, paths, and shelters can be destroyed virtually overnight by a fierce storm or more slowly by the insidious processes of erosion. The reader should therefore keep in mind that the text of this book reflects the conditions as they appeared when the writer or his trail checkers were personally on the scene observing the country. But to adopt an old phrase, the bridge that is here today may be gone tomorrow, and visitors to the wilderness should come prepared for change.

During the half-century that has swept by since I began seeking the solitude of the Olympics, considerable change has occurred in other aspects of the wilderness experience. In the good old days fifty years ago, regulations were few, gasoline inexpensive, and backcountry permits, although required, were seldom checked by the rangers. One could camp just about anywhere he or she wished, and fires could be built in any established campsite. One could also drink the water straight from the mountain streams without fear that it might be polluted and cause illness.

Some time along about the mid-1970s, the size of overnight parties going into the Olympics was limited, both by the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service, to a dozen persons. Fires were forbidden in most subalpine areas, and a reservation system was adopted for popular areas in an attempt to give everyone an equal opportunity to enjoy this wilderness. The ban on fires was instituted chiefly to save the picturesque ghost forests left by natural firesforests that were becoming increasingly depleted because campers chopped them down for firewood.

When I wrote what became the first edition of Olympic Mountains Trail Guide, I included detailed descriptions of several trails or parts of trails that had been abandoned by the National Park Service and the Forest Service and were no longer maintained. I included them not only to preserve their historical value but also with the hope that putting them in the guidebook would encourage the government agencies involved to reopen these once-excellent trails. Unfortunately, it did notperhaps not because of disinterest by the agencies but due to limited funds budgeted for trail maintenance and restoration. Be that as it may, abandoning these trails and not showing them on current maps (and letting nature return them to the wild) makes the areas traversed by such trails essentially inaccessibleand thus presents a good argument for deleting these lands from either the national park or the Forest Services wilderness areas and again making them available to logging or other commercial activities. If they cannot be visited due to the absence of reasonably maintained trails, why retain these lands in a national park or wilderness area?