CONTENTS

This book would not have been possible without the wealth of material provided by our local newspapers. I have acknowledged all the directly quoted material and have tried to contact the papers concerned to seek their agreement for its use. However, it would appear that a number of the papers are no longer published, at least under their wartime titles. If I have missed any, please accept my apologies. Please let me know via the publisher, and I will try to remedy matters in any future edition of the book. Quotes from the Oxford newspapers appear courtesy of Newsquest Oxfordshire. The copyright of all directly quoted material belongs to the relevant newspapers referenced in each case. My thanks also go to the librarians and archivists in libraries and records offices up and down the country, who look after this material.

A word of explanation is needed. There is already a wealth of excellent books about what life was like in Britain during the extraordinary years of the Second World War. Why do we need another one?

The idea came up when The History Press decided to reprint my local history of Reading at War. This was based on local newspaper reports of the period, and through them I tried to capture a flavour of what it felt like to live in that community through these times. Many histories of the period are seen through one of two perspectives: either the historian applies his or her forensic analysis, nourished by the wisdom of hindsight, or they are the recollections of one or more individuals who lived through the war. Valuable, vivid and valid though both of these approaches may be, to my mind neither captures the full picture.

Journalism is said to be the first draft of history, and provincial newspaper reports of the period, whatever one may say about some of their journalistic shortcomings, sometimes capture the spirit of the times in a way that other chroniclers do not. Although the stories they carry are often rooted in their locality, their themes tend to have a much wider relevance. In them, we see the editorial efforts to stir the readership to greater war efforts or to seek out the bright side even in the darkest days of the war. We learn how the people looked for normality and diversion in such strange times; the mind-boggling detail of the bureaucratic control the authorities sought to exercise over wartime life (and sometimes their incompetence in doing so); the ingenuity or ineptitude of the criminal classes in trying to circumvent those rules (and the fact that a large part of the normally law-abiding population found themselves, wittingly or unwittingly, committing offences against the impenetrable jungle of wartime regulation); and the efforts of the business community to drum up new lines of custom from the war. The accounts were revealing and often (sometimes unintentionally) funny.

What I have therefore done is to start by drawing material from the three wartime histories of the Home Front that I have already written, and complemented them with similar accounts from more than twenty local newspaper reports covering other communities up and down the country. I hope in this way to present an anthology which gives some insight into what life was like for the British civilian population in those times.

The approach does not claim to be an authoritative or comprehensive overview of the period. Like all first drafts, press reports could be prone to error or misinterpretation. Some aspects of life which are of interest to us now might not have been considered newsworthy at the time, and vice versa. All other considerations aside, the censor's pen could have a marked impact on what was reported and how it was covered. Nonetheless, I hope my book nicely complements the many fine books which give the grand sweep of that period of history, a selection of which are acknowledged in my bibliography.

* Reading at War (Sutton 1996, The History Press 2011), Kent and Sussex 1940: Britains Front Line (Pen and Sword 2004) and Their Darkest Hour (Sutton 2001, reprinted as Careless Talk, The History Press 2010).

1

WAR IS GOOD BUSINESS

EARLY DAYS

This is what is known as the silly season when, apart from Hitler (who is in any case one of the silliest creatures in the world) the newspapers can't find much to write about. Slough appears to be suffering from the complaint as much as anybody hardly a single good meaty subject in the news worth getting one's teeth into

Slough Observer editorial, the week before war broke out

The First Days of War

The hope that war could be avoided was shared by a large proportion of the population, right up until the end of peace. As late as 24 June 1939 the Illustrated London News was carrying an advertisement from German Railways, promoting tourism:

Seeing is believing. Come and see Germany.

Visitors from Britain are heartily welcomed at all times.

They will find that friendliness and the desire to help are the characteristics common to every German they meet.

London Illustrated News, 24 June 1939

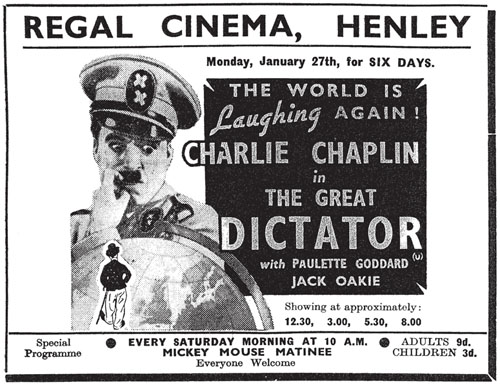

For its part, Picture Post in late July carried a piece, written in both English and German, entitled We want peace Britain does not hate Germany. Readers were urged to send a copy to their contacts in Germany. Even the Americans got involved, their State Department bringing pressure to bear on Charlie Chaplin to delay production of his Hitler satire The Great Dictator, for fear of offending the real dictator. A survey at the end of August suggested that only 18 per cent of the British public thought war would break out. Most thought Hitler was bluffing, and would step back from the brink. When it became clear that Hitler was not bluffing, the feeling was that he had made a massive miscalculation in assuming that he could win a lightning victory over the Poles before the Allies could mobilise support for them. There was a third, equally misplaced, hope:

The film The Great Dictator finally got released, despite fears that it might offend the Fhrer.

The German people themselves may revolt against the black act that is being done in their name. If they do, the people of this land will be the first to come to their aid to secure the re-establishment of law and order in their country.

Swindon Advertiser, 2 September 1939

But readers of the letters page of the Hampshire Chronicle had more than hope to rely on:

As an Associate of the Federation of British Astrologers I think it unlikely that war will result from the present crisis. Astrologically, the chances are no more than two in six.

Letter to the Hampshire Chronicle, 26 August 1939

On the very same page, a spiritualist wrote in to report that several sances had revealed to him that there would be no war. In one, no less a figure than the newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe (who died in 1922) had been in touch with the medium and had described the following scene to him:

I see a very high mountain with a vast plain at the foot the plain is filled with legions of armies, all armed ready for war. They rush up the mountain but at the top they are halted The white-robed and radiant figure of Jesus stands before them. On each side are white-robed figures bearing palms and rejoicing in the great victory of peace.

Letter to the Hampshire Chronicle, 26 August 1939

By the end of September, the latest edition of the magazine Psychic Review was being advertised in the same paper; its cover story? False no war prophesies exposed: Enquiry demanded.