1

Place of Death

I am very sad. Technology is great but I like to hold my newspaper in my hand. Its handy and you dont need a password. Its just there and I will miss not having that.

Two first-term members of Congress, John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon, boarded the Capitol Limited train at Washingtons Union Station on the Monday morning of April 21, 1947, headed to McKeesport, Pennsylvania, the economic and spiritual center of the Monongahela River valley and home to one hundred thousand unionized industrial workers. As the two newest members of the House Labor and Education Committee, the lawmakers were scheduled to appear that night at the Penn-McKee Hotel before more than one hundred people at an event sponsored by the local Junto Forum, a business-minded civic group. The men planned to debate the Hartley labor bill, which would eventually become the Taft-Hartley Act and set new rules for organized workers at a time of widespread labor strikes and heightened fears over communism.

Nixon, then thirty-four, spoke rigidly that night as he defended the rights of business owners to set limits on striking laborers; Kennedy, a boyish twenty-nine, maintained a more casual manner and talked about how unions needed to protect industrial workplaces from turning into sweatshops. Both kept up an evenhanded conversation despite some union members in the audience who turned agitated. Naturally, I was slightly prejudiced because I am Republican, but at the same time, I was impressed by Kennedy, moderator William C. Baird

For the two Navy veterans at the center of the debate, the visit to southwestern Pennsylvania helped them form a bond: after the presentation, six Junto members took the lawmakers to the Star Restaurant across the street from the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad station for coffee and sandwiches while they waited for the midnight train back to Washington. On the long ride back, the men stayed up late talking about how to handle communist threats in the United States and overseas. Of one thing I am absolutely sure, Nixon later wrote. Neither he nor I had even the vaguest notion at the time that either of us would be a candidate for president thirteen years later.

For McKeesport, the original event in 1947 underscored the industrial communitys political and economic relevance. At one time, residents of the city had imagined that they might build a steel empire to rival that of larger, more established Pittsburgh, twelve miles downriver. That dream never came to fruition, but McKeesport, which sits at another confluence, of the Monongahela and Youghiogheny rivers, did dominate the Mon Valley with its manufacturing and blue-collar workers. National Tube Works opened a factory in 1872 to turn out pipes made from iron sheets rolled into tubes and welded. By the end of the nineteenth century, the company had started making its own iron and then steel for seamless pipes, and it manufactured about 70 percent of all steel tubing in the United States. Within another few years, National Tube Works merged into the newly formed U.S. Steel, its factories occupying nearly all the riverfront through McKeesport, and the company gave the city its moniker of Tube City.

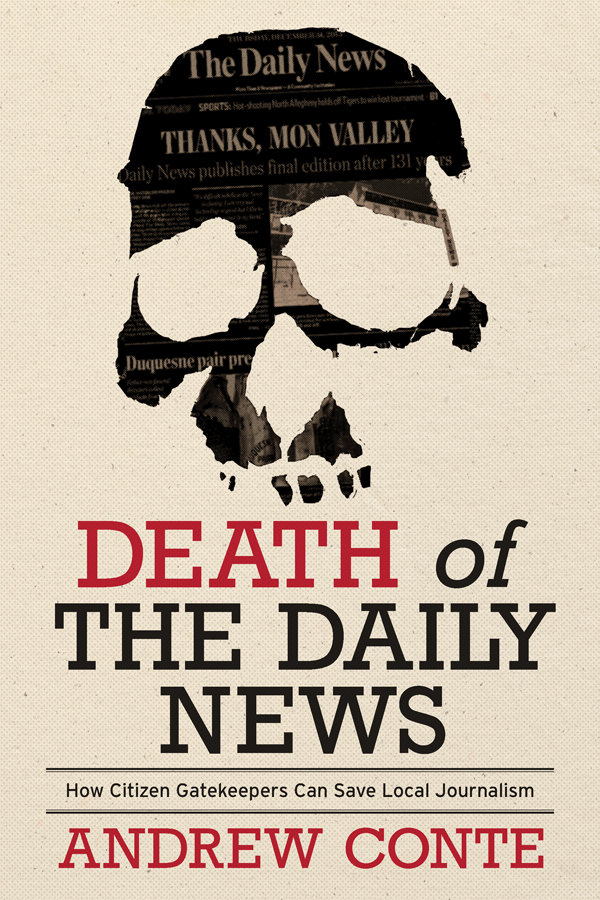

Around the same time that National Tube Works started out, in 1884, three local menEdward B. Clark, Harry S. Dravo, and William B. Dravodecided to start their own newspaper, the Daily News, to compete with the existing McKeesport Times, where the Dravos had been working.by private electric light in 1889, and later, when the Daily News opened an iconic art deco building at the heart of the city in 1938, it had the citys first air conditioning. Purchased in 1925 by four local men, including a prominent local politician, State Senator William D. Mansfield, who served as publisher for the rest of his life, the newspaper eventually grew to have 46,836 subscribers in the early 1970s, with about 130 employees. As a reminder to readers of its place in their lives, the newspaper carried a slogan beneath the nameplate at the top of every front page: More than a newspaper, a community institution.

All of McKeesports manufacturing production, in turn, supported a thriving community with some fifty-five thousand residents at its peak in the 1940s. McKeesport had been home to the first G. C. Murphy five-and-ten-cent store, and the city served as the companys headquarters, with 560 outlets spread across twenty-four states. McKeesport boasted a half dozen movie theaters, several furniture stores and jewelry shops, and more than seven hundred retail stores, including three big department storesCoxs, Jaisons, and Imels.

The city retained so much importance that Kennedy returned as president on October 13, 1962, just days before the Cuban Missile Crisis unfolded, and spoke to a crowd of twenty-five thousand people. He stood on a wooden stage with red, white, and blue bunting hanging from it and a tent erected overhead. The dais sat at the spiritual center of the city in a small grassy parklet between the municipal building and the art deco home of the local newspaper, the Daily News. Some people had slept overnight to be near the front of the crowd, and afterward the audience thronged so close to the stage that its railing collapsed. The first time I came to this city was in 1947, when Mr. Richard Nixon and I engaged in our first debate, Kennedy said to laughter and cheers that day.

Like Pittsburgh and river towns throughout southwestern Pennsylvania, McKeesport fell on hard times in the 1970s and 1980s as foreign steel imports undercut American manufacturers and the steel industry collapsed under the weight of out-of-control spending and out-of-date infrastructure. McKeesports population shrank to less than twenty thousand, and its famed business district withered away under the dual pressures of economic decline and the growth of suburban shopping malls. Workers boarded up two multistory parking garages near the city center, and blocks of retail shops and offices around City Hall were

Then at the end of 2015, the city suffered another major blow: the McKeesport Daily News, the newspaper that had been operating for 131 years at the center of the city, near the site where the Kennedy statue stands, rolled the last of its forty thousand-plus editions off the presses in the basement of its art deco home and closed.

We grew up knowing that our personal life-changing eventsgraduations, weddings, births and deathswere all recorded in the newspaper, State Senator Jim Brewster, who delivered the newspaper as a boy and later worked at a newspaper before going into politics, said at the time. The Daily News was on-the-scene when elections were won or lost; when projects succeeded or failed. It reliably reported school happenings, sporting events, crimes, fires, burglaries, and robberies.

Ernie Harkless, who had worked at the Daily News for more than forty-four years, summed up the feelings of many when he lamented the loss of the printed newspaper: I am very sad. Technology is great but I like to hold my newspaper in my hand. Its handy and you dont need a password. Its just there and I will miss not having that.