The

Secret History

of

Vampires

THEIR MULTIPLE FORMS

AND HIDDEN PURPOSES

CLAUDE LECOUTEUX

Translated by Jon E. Graham

Inner Traditions

Rochester, Vermont Toronto, Canada

To Anneliese and Benot

Introduction

From my grave to wander I am forcd

Still to seek the Goods long severd link,

Still to love the bridegroom I have lost,

And the life-blood of his heart to drink.

GOETHE, THE BRIDE OF CORINTH (1797)

THAT THE DEAD are capable of returning to afflict the living is a belief that goes back to the dawn of time: revenants are rarely motivated by good intentions. From this thought, the human imagination has conjured various forms that are little known to us, because, starting in the eighteenth century, they were all supplanted by a vampire whose image has gradually been crystallized by the famous Dracula immortalized by Bram Stoker (18471912) in a novel that has never gone out of print. In fact this novel continues to serve as inspiration to other writers and filmmakers. In 1993 Fred Saberhagen and James V. Hart even adapted this story for the theater.

For a large part of the public, the vampire is a bloodsucker who comes to sleepers at night and brings about their slow deaths by siphoning away their vital substance. Novels and films have familiarized us with this person who allegedly dreads garlic and the cross, this living dead who fears the light of day. When the sun is shining, he remains in his coffin or in a chest filled with earth from his grave. Here he sleeps with eyes wide open while rats defend him from any who might come near. A true living dead, the vampire has pale skin, overdeveloped and pointed canine teeth, vermilion lips, and long fingernails. His hand is icy cold and has a grip of steel. He leaves his haven to the accompaniment of ferociously howling dogs or wolves, and when he slips into a house, he causes the people watching over it to fall into inescapable torpor. Some assert that he can metamorphose into a fly, a rat, or a bat; that in this form he can spy upon the conversation of those pursuing him; and that he can communicate with his fellow vampires by telepathy. He can climb down the sheer walls of his castle like a lizard.

These details are based on long traditions that have come down from a remote past. Stoker put them together to produce what would become the myth of the vampire. He was inspired by earlier authors, but none had ever painted such a rich picture. William Polidori had shown the way with The Vampyre, a Tale in 1819.

Some great names have affixed their signatures to vampire stories, including Prosper Mrime (1872) with La guzla, Charles Baudelaire, Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Felix Dahn, Alexander Dumas, Hans Heinz Ewers, and Thophile Gautier. Who could think of denying the importance of this theme in the human imagination?

Sociologists explain the flourishing of vampire-themed literature and films as the combination of meaningful themes such as illness, death, sexuality, and religiosity. Furthermore, they have demonstrated that the vampire lends itself to political recuperation. Since 1741 the word vampire has taken on the meaning of a tyrant sucking the life from his people, and Voltaire declared the real vampires are the monks who eat at the expense of the kings and the people.

The success of vampires certainly resides in this power, and it is a quality that never fails: a rapid search of the Internet yields more than two hundred fifty home pages dedicated to them, with discussion forums and chat rooms! The addresses are particularly delicious: The Vampire Garden, Vampires Universe, The Vampires Lair, Vampire Mud, and so forth. We can note from an Internet search that there is a Transylvanian Society of Dracula, which publishes a bulletin called the Internet Vampire Tribune Quarterly, as well as vampirethemed nightclubs. In short, the fans of macabre curiosities are rather spoiled.

A terrifying figure because of its ungraspable qualities, the vampire has haunted the imaginal realm for centuries and excited the sagacity of scientists who have been seeking a satisfying explanation for his posthumous wanderings. As early as 1679, Philippe Rohr dedicated a dissertation to the dead that feed in their graves, a subject picked up anew by Otto in 1732 and again by Michal Ranft in 1734. Ranft distinguished ties between vampirism and nightmares and believed it was all illusion prompted by a fertile imagination. Other scholars continued this endless argument: Gottlob Heinrich Vogt, Christoph Pohl, and an anonymous writer who signed his texts the Weimar Doctor devoted themselves to discussing the presumed nonputrefaction of vampires. This characteristic brought up a theological problem: theoretically, only the bodies of the excommunicated did not decompose. In 1733 Johann Christoph Harenberg did a complete turn around the matter, and in 1738 the Marquis Boyer dArgens analyzed examples of vampirism.

Yet what gave substance to the belief in vampires and inspired a flood of scholarly treatises were reports from the authorities, such as those published in Belgrade in 1732 by Lieutenant Colonel Bttener and J. H. von Lindenfels on the vampires of the Serbian town of Medvegia

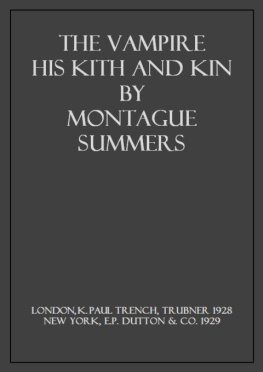

This huge mass of writing fed the contemporary imagination, but it also was the origin of errors and distortions suffered by the original belief, the origin of received notions and, most important, of the stupefying reduction of several types of wicked dead to the vampire alone. The books devoted to these bloodsuckers for decades have done little to restore them to their original appearance. They seem intended for the public at largethe same public that rushes to the theater in order to shiver with comfortable horror. These books have also given substance to the received notions with more or less good fortune, and rare are the objective studies that present the phenomenon and analyze it without falling into irrationality or without turning to the support of parapsychology or psychiatry.

My goal in this books investigation is, through reliance on firsthand testimonies, to create a work of demystification, to rediscover the subject of an ancestral belief and uncover the mind-set in which the vampire is rooted. In my opinion, this anchoring in realityeven if this reality is no longer ours and we experience the greatest difficulty trying to plumb the motives of our ancestors mind-setis the most important factor if only because of its anthropological dimension. The vampire forms part of the misunderstood history of humanity. He possesses a role and a functionhe did not just spring from nothingness in the seventeenth or eighteenth century! He fits within a complex set of representations of life and death that has survived into the present, although clearly with a lesser richness than in the remote pasta past that people tend to confuse with the Dark Ages, those backward and ignorant times that were banished by reason and the Age of Enlightenment.

Yet it is startling that it was in the century of the Enlightenment that vampires spread like an epidemic into every region. Isnt this a curious fact? It seems that in the effort to enlighten minds, it was necessary to take up again, analyze, and dissect the ancient beliefs in order to display all their inanity. Of course! But the effect was only partial, and arguments convinced only those who were already persuaded that the ancient beliefs represented overheated senses, optical illusions, or a disordered imagination. Vampires, however, have never ceased fascinating the living, no doubt because they are a rift in the framework of scientific certitudes so seamlessly woven that it seems they should never have to suffer the assault of the impossible, as Roger Caillois says.

Next page