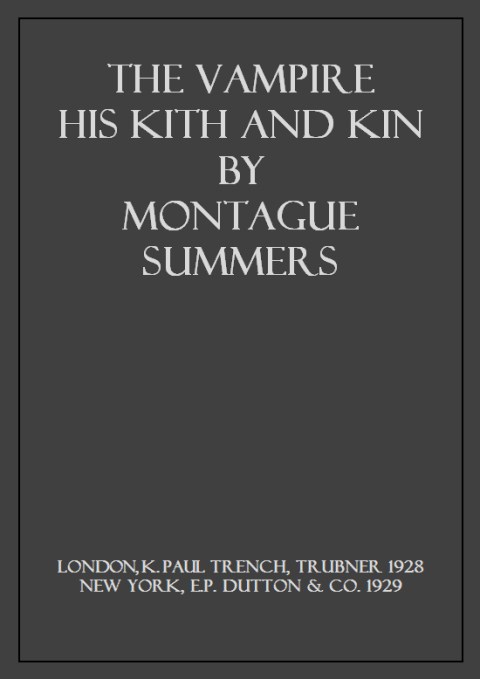

The Vampire, His Kith And Kin By Montague Summers

INTRODUCTION

IN all the darkest pages of the malign supernatural there is no more terrible tradition than that of the Vampire, a pariah even among demons. Foul are his ravages; gruesome and seemingly barbaric are the ancient and approved methods by which folk must rid themselves of this hideous pest. Even to-day in certain quarters of the world, in remoter districts of Europe itself, Transylvania, Slavonia, the isles and mountains of Greece, the peasant will take the law into his own bands and utterly destroy the carrion who--as it is yet firmly believed--at night will issue from his unhallowed grave to spread the infection of vampirism throughout the countryside. Assyria knew the vampire long ago, and he lurked amid the primaeval forests of Mexico before Cortes came. He is feared by the Chinese, by the Indian, and the Malay alike; whilst Arabian story tells us again and again of the ghouls who haunt ill-omened sepulchres and lonely cross-ways to attack and devour the unhappy traveller.

The tradition is world wide and of dateless antiquity. Travellers and various writers upon several countries have dealt with these dark and perplexing problems, sometimes cursorily, less frequently with scholarship and perception, but in every case the discussion of the vampire has occupied a few paragraphs, a page or two, or at most a chapter of an extensive and divaricating study, where other circumstances and other legends claimed at least an equal if not a more important and considerable place in the narrative. It maybe argued, indeed, that the writers upon Greece have paid especial attention to this tradition, and that the vampire figures prominently in their works. This is true, but on the other band the treatise of Leone Allacci, De Graecorum hodie quorundam opinationibus, 1645, is of considerable rarity, nor are even such volumes as Father Franois Richard's Relation de ce qui s'est pass de plus remarquable a Sant-Erini, 1657, the Voyage au Levant (1705) of Paul Lucas, and Tournefort's Relation d'un Voyage du Levant (1717), although perhaps not altogether uncommon and certainly fairly well known by repute, generally to be met with in every library. The study of the Modern Greek Vampire in Mr. J. G. Lawson's Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion has, of course, taken its place as a classic, but save incidentally and in passing Mr. Lawson does not touch upon the tradition in other countries and at other times, for this lies outside his purview.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, and even more particularly during the first half of the eighteenth century when in Hungary, Moravia, and Galicia, there seemed to be a veritable epidemic of vampirism. the report of which was bruited far and wide engaging the attention of curia and university, ecclesiastic and philosopher, scholar and man of letters, journalist and virtuoso in all lands, there appeared a large number of academic theses and tractates, the majority of which had been prelected at Leipzig, and these formally discussed and debated the question in well-nigh all its aspects, dividing, sub-dividing, inquiring, ratiocinating upon the most approved scholastic lines. Thus we have the monographs of such professors as Philip Rohr, whose "Dissertatio Historico-Philosophica" De Masticatione Mortuorum was delivered at Leipzig on 16 August, 1679, and issued the same year from the press of Michael Vogt; the Dissertatio de Uampyris Seruiensibus of Zopfius and van Dalen, printed at Duisburg in 1733; and the De absolutione mortuorum excommunicatorum of Heineccius, published at Helmstad in 1709. Of especial value are Michael Ranft's De Masticatione Mortuorum in Tumulis Liber, Leipzig, 1728, and the Dissertatio de Cadaueribus Sanguisugis, Jena, 1732, of John Christian Stock. These dissertations, however, are extremely scarce and hardly to be found, whilst even so encyclopaedic a bibliography as Caillet does not include either Philip Rohr, Michael Ranft, or Stock, all of whom should therein assuredly have found a place. In this connexion must not be omitted the De Miraculis Mortuorum, Leipzig, Kirchner, 1670, and second edition, Weidmann, 1687, a treatise by Christian Frederic Garmann, a noted physician, who was born at Mersebourg about 1640 and who practised with great repute at Chemnitz. Garmann discusses many curious details and continued to amass so vast a collection of notes that after his death there was published in 1709 at Dresden by Zimmerman a very much enlarged edition of his work, "exornatum, diu desideratum et expetitum, beato autoris obitu interueniente."

During the eighteenth century the tradition of the Vampire was dealt with by two famous authors, of whom both concentrated upon this as their main theme, that is to say by Dom Augustin Calmet, O.S.B., in his Dissertations sur les Apparitions des Anges, des Dmons et des Esprits et sur les revenants et vampires de Hongrie, de Bohme, de Moravie, e de Silsie, Paris, 1740, and by Gioseppe Davanzati, Archbishop of Trani and Patriarch of Alexandria, in his Dissertazione sopra I Vampire, Naples, 1774. As I have very fully considered both these important works they require no more than a bare mention here.

Of a later date we find in French a few books such as the Histoire des Vampires (1820) of the enormously prolific Collin de Plancy, the Spectriana (1817) and Les ombres sanglantes(1820) of J. p. R. Cuisin, and Gabrielle de Paban's Histoire des Fantmes et des Demons (1819) and Dmoniana (1820), but these with many more of that class and epoch, although they are sometimes written not without elegance and industry and one may here and there meet with a curious anecdote or local legend, will not, I think, long engage the consideration and regard of the more serious student.

In English there is a little book entitled Vampires and Vampirism by Mr. Dudley Wright, which was first published in 1914; second edition (with additional matter), 1924. It may, of course, be said that this is not intended to be more than a popular and trifling collection and that one must not look for accuracy and research from the author of Roman Catholicism and Freemasonry. However that may be, it were not an easy task to find a more insipid olio than Vampires and Vampirism, of which the ingredients, so far as I am able to judge, are most palpably derived at second, and even at third hand. Dom Calmet, sometimes with and sometimes without acknowledgement, is frequently quoted and continually misunderstood, In what the "additional matter" of the second edition consists I cannot pretend to say but I have noticed that the same anecdotes are repeated, e.g. on p. 9 we are told the story of a shepherd of "Blow, near Kadam, in Bohemia," and the relation is said to be taken (via Calmet, it is plain,) from "De Schartz [rather Charles Ferdinand de Schertz], in his Magia Postuma, published at Olmutz in 1706." On p. 166 this story, as given by "E. p. Evans, in his interesting work on theCriminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals," is told of "a herdsman near the town of Cadan," and dated 1337. Pages 60-62 are occupied with an Oriental legend related by "Fornari, in his History of Sorcerers," by which is presumably intended the Histoire curieuse et pittoresque des sorciers... Revue et augmente par Fornari, Paris, 1846, and other editions, a book usually catalogued under Giraldo, as by Caillet and Yve-Plessis, although the latter certainly has a cross-reference to Fornari. In greater detail Mr. Dudley Wright narrates this legend which be has already told (pp. 60-62), on pp. 131-137. Such repetition seems superfluous. In the Bibliography we have such entries as "Leo Allatius,"

Next page